BOBBIE BOWMAN

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 BOBBIE BOWMAN

[Compiled November 16th, 2010]

Interviewee: BOBBIE BOWMAN

Interviewer: Carter Sickels

Interview Date: August 7th, 2010

Location: Lawndale, North Carolina

Length: Approximately 37 minutes

CARTER SICKELS: Okay, this is Carter Sickels interviewing Bobbie Bowman in Lawndale, August 7th, 2010. So could you just say your name, the date that you were born, and where you were born?

BOBBIE BOWMAN: Bobbie Bowman, March 27, 1930, in Catawba County.

CS: Okay.

BB: Today is my daughter%u2019s birthday.

CS: Oh, is it? Are you doing anything special?

BB: No, because, as I say, she%u2019s%u2026

CS: %u2026She%u2019s too far away. [Laughter]

BB: They were through here a few weeks ago, going to help a son of hers relocate back down to Nashville, Tennessee from Wisconsin, and I just gave her a card. I give them money; I don%u2019t buy gifts.

CS: Yeah, well, money%u2019s always good. Now where did you say you were born again?

BB: I was born in Catawba County, up in the Cooksville area.

CS: Okay. Were your parents born in that area?

BB: Yes.

CS: Yeah. And you said you were one of ten? How many?

BB: First, there was four boys, then five girls, which I was the oldest.

CS: Oh, you were the oldest girl.

BB: And then I had a younger brother, but I%u2019m the oldest one living now, I and two of my sisters and a brother are the only ones that are left.

CS: Okay. I%u2019m just going to ask you a little bit about growing up and what that was like before I move on to the mill stuff.

BB: Before?

CS: Yeah, I%u2019ll just start there. Did you live on a farm or in town?

BB: Yes, we lived on a farm not far from the Jacob%u2019s Fork River. We spent our Sunday afternoons in the river. I don%u2019t know how we kept from being drowned. It wasn%u2019t that deep, but I never did learn to swim and I%u2019m still scared of water. I vowed when my children come they would know how to swim, so I carried them to Shelby and had swimming lessons.

CS: That was good. So what kind of things did you all farm?

BB: Mostly cotton was the cash crop. We did raise some corn for the mules that they used to plow with. We didn%u2019t even have a car until I was probably ten or eleven years old. We used to come out to Fallston. I don%u2019t know what you know about the background of Stamey%u2019s Store.

CS: I don%u2019t know.

BB: It was a store in Fallston that you could buy clothes and all that. So, we%u2019d come out there in a two-horse wagon every fall to buy our school clothes. I told that one time down here at the office, and this girl just died laughing. She couldn%u2019t believe that. She thought I was making it up, and another lady that worked there in the office lived in Fallston and she said, %u201CThat%u2019s true. You know, they did come in there,%u201D but I don%u2019t know why Jane thought I was making that up. It was an all-day trip.

CS: Yeah, how long did it take?

BB: It was about seventeen miles.

CS: Was it? So how long would that take to get there then, do you think?

BB: Well, it would probably take a couple of hours.

CS: Yeah. What kind of responsibilities did you have when you were young?

BB: We helped hoe the cotton. We worked in the fields in the summer, and I guess it was my youngest sister, I caught all the childhood diseases when my brothers brought them home, and I was told I had whooping cough when I was three weeks old, but a sister under me began to bring home diseases when she went to school. So, all the ones below me had all the childhood diseases, and this youngest sister of mine, the measles affected the nerve in her ear. She was deaf; we had to take her to the deaf school, but she had been examined and they said she only had ninety percent hearing. Mom was tied up with the cooking and all the other young%u2019uns, so it was my job to tend to her. When I started dating my husband, she would--we%u2019d go on a date on Sunday and he%u2019d always bring me home because he wanted to see me milk. One of my chores was milking the cow. [Laughter]

CS: [Laughter] He liked that?

BB: We had two cows. My sister, she%u2019d say, %u201CMama, Bobbie, boo!%u201D You know, she%u2019d do like that.

CS: Cross her arms?

BB: Uh-huh. She didn%u2019t like him; she%u2019d go around and she%u2019d have candy corn or something and put a piece of corn at everybody%u2019s plate, but she wouldn%u2019t put one at Bud%u2019s. [Laughter]

CS: That%u2019s funny. So you had cows, and did you have hogs?

BB: Yeah, you raised your own meat. You had hog meat, and usually, at that time somebody would kill a cow, or, you know, cattle, and they%u2019d bring it by and peddle it and you%u2019d buy a mess of meat.

CS: Oh, wow. Okay.

BB: Which wouldn%u2019t probably be considered sanitary now, but it was probably safer than some of this stuff you buy at the markets.

CS: It probably was. But most of the food, you raised yourself?

BB: Yes.

CS: Vegetables and--?

BB: And if we got a Coca-Cola one time a year, we thought we were really living in high cotton.

CS: Once a year?

BB: Yeah.

CS: Would you get that when you went into town for your shopping?

BB: I don%u2019t remember. Well, my uncle down below where we lived, maybe it was as far as from here up there to them that the road had a store. My mama had chickens, and her egg money bought the groceries, and Dad%u2019s farm brought in his money, but they had separate money. We raised everything we eat except sugar and--. And I think they used to take wheat to the mill and have it ground. We made our own flour.

CS: Wow. And butter? Did you make your butter?

BB: Yeah. I said we grew up on skim milk because my mama skimmed the cream off and sold it once a week and churned it. I said we grew up on skim milk.

CS: Did you have to do that at all? Did you churn?

BB: Yeah, sometimes. We did a pretty good size glass jar.

CS: Okay.

BB: Now that old--my husband bought that just as a novelty. We set it over there on the hearth, but some people use those type things.

CS: What kind of things did you all do for entertainment? You said you swam in the river, played in the river.

BB: We made playhouses. We%u2019d go down in the woods and play. And we didn%u2019t have electricity %u2018til I was about ten or twelve years old. We used to go to Sunday school, walked to church barefooted. It was maybe as far as from here out there to 182, but I know they%u2019d always say, %u201CWell, going barefooted, your foot just spreads out,%u201D but you know, kids grow. Now, I know it used to be my grandchildren%u2019s achievement when they come home, to get as tall as Mee Maw. The first thing they did when they come in--would measure to me, and it didn%u2019t take them long to pass me. I was telling my son%u2019s little boy that a year or so ago, so know he measures. Kids at a certain age take a growing spurt. Back in the spring he was just up to about here, but he%u2019s up to here now.

CS: Wow.

BB: So that%u2019s what happened to your feet; they grew too.

CS: How far did you have to go to school?

BB: Well, probably four or five miles. We had a bus that came by.

CS: You had a bus?

BB: But at one time, it didn%u2019t come by the house. We had to walk maybe as far as from here out there to the end of the road down to connect with another road where they did pick up all of them.

CS: Did anyone in your family play any music or do any singing or anything?

BB: No, one of my older brother, he would always--I mean, he wanted to learn to play a guitar and he bought one, but, you know, strummed on it. The thing he always sung was %u201COn the Wings of a Snow-White Dove.%u201D I didn%u2019t care that much for that song, but it was funny--when my husband died, I had picked out one of the songs at the funeral and I told this lady that was singing, %u201CYou just pick out one,%u201D and she said, %u201CI just think this is an old Lawndale song,%u201D and she began to sing that song, and my children says, [makes gasping sound] so when we were on the way over to the cemetery, I said, %u201CWhy did y%u2019all gasp when Martha sang that song?%u201D I worked down in the office from eight to five, and Bud worked in the mills and at J.P.Stevens; he%u2019d work from six to two. They said, %u201CEver time when Daddy come home, he put that record on and played it.%u201D [Laughter] I don%u2019t care a lot for guitars.

CS: Your husband%u2019s name was Bud?

BB: His name was Harold but everybody called him Bud.

CS: How did you all meet?

BB: A friend of his was dating a girl in the area where I grew up, and he brought Bud up there one day, so that%u2019s how we got hooked up.

CS: When did you get married?

BB: We were married in %u201948.

CS: Okay.

BB: No, wait a minute; I finished school in %u201948. I went to Mitchell College in Statesville%u2026

CS: %u2026Oh, you did? Okay%u2026

BB: %u2026and took a one-year business course, and we got married in %u201949.

CS: Okay. So he worked in the mill, and then you worked in the mill also?

BB: I worked in the office, yeah.

CS: When did you start working there?

BB: We moved down here in the fifties and I started, and at that time--. Have you been by the mill?

CS: Um-hmm. Which mill is it that you worked at?

BB: It was called Cleveland Mill and Power Company then because the mill generated its power and sold power to the people. While you%u2019re over here, you just ought to ride over there, and I%u2019ll go with you if you want me to.

CS: Okay.

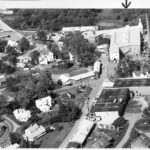

BB: But you first came in a company store, and then back toward the back on the right was the little area where the women that did the office work worked. On one side of that--well, let%u2019s see, on one side of the company store was the post office, and above it was Dr. A.C. Edwards%u2019 office, the dentist%u2019s office. Then they eventually took the company store and did away with that and eventually put the office, the main office, in there. Somebody said it was bought by a man from Mexico, I think, and ran it for a year or two, but they stripped all the copper out of the plant, and they%u2019re over there now, just tearing everything out. It looks like%u2026

CS: %u2026That%u2019s terrible%u2026

BB: %u2026they%u2019ve hauled off several big loads of metal, and somebody has said--I don%u2019t know how true it is, that [telephone ringing] all the old, they%u2019re tearing down all the old and they%u2019re going to make a park over there. [Recorder is turned off and then back on] I thought maybe they were going to try to make a water park, but then I heard later, maybe a type of greenway thing, so I don%u2019t really know.

CS: So you moved here in the fifties? You and your husband moved here in the fifties?

BB: Yeah.

CS: Did he work somewhere before he started the (00:22)?

BB: He was working down here in the plant at that time.

CS: Okay. What was his job?

BB: I don%u2019t remember.

CS: And then did he change positions?

BB: Well, later on, he went to J.P. Stevens in Shelby because they paid a better wage.

CS: Do you know what he did there? Did he work in the weaving room?

BB: He was a fixer.

CS: He was a loom-fixer?

BB: And eventually worked up to a supervisor.

CS: Okay. And you worked in the office for how many--when did you retire?

BB: In [pause]. My brain%u2019s not what it used to be.

CS: Oh, that%u2019s all right.

BB: I think the plant closed in 2001, and I had been retired a couple of years, but I would still go back over there and fill in for the lady that ran the switchboard, when she needed to be out or something. I was working over there the day that Mr. Elder, who was the--I%u2019ll say, for lack of a better description, CEO--came in and said that they were closing the plant. I think it was GE-something that was seizing the plant, so everybody had to go home. They did eventually let--and my son was a fixer down there at that time--they did eventually let the people come back in the plant and get their tools, because if they were fixers or something like that, they had to furnish their own tools.

CS: What was that like when all the mills started closing, I guess in the nineties, right?

BB: Yeah, there was--I mean, we weren%u2019t the first one that had closed.

CS: Right.

BB: Well, when they were Cleveland Mill and Power the Schencks owned it; it was owned locally.

CS: Local.

BB: And then, on down the road--. Excuse me. I%u2019ll get some water and get my throat to working. [Recorder is turned off and then back on again] The Schencks sold it to Spartan Mills in Spartanburg, and we were under their management from then on. When I went to work down there, they were just making yarns. You know, not like the knitting yarn but a thread yarn, and then they expanded to making a knit fabric. Of course, they built on to it and were making a knit fabric. I forget what it was called, but their two major customers was Chrysler and Ford. Then they expanded into apparel knits, which was knitting like underwear and things like that.

CS: Okay.

BB: They built a building that was there on-site that was called the knitting building, and then they had a building out beyond the machine shop that was called the finishing plant.

CS: When you moved here in the fifties, were people still living in the company houses?

BB: Yes. I think they were in the process of selling them to the employees, or they had been sold, but it was along about that time.

CS: Can you tell me a little bit about just what your job was or what it entailed?

BB: Well, I just did general typing. I entered orders for a while, and later on, Charlie Forney--I don%u2019t know if you%u2019ve heard that name before if you%u2019re not in the county.

CS: I haven%u2019t.

BB: They lived here and I worked here when they worked under the Schencks. John Schenck was the president and then Charlie Forney was the next in command. They decided--No, they first put in a switchboard at the front, and I got the job of running the switchboard.

CS: Okay.

BB: And then, Charlie Forney decided he needed a secretary, so he asked me if I%u2019d like to have it, so I took it, and I worked for him. Over the years, I usually worked for the superintendent or the assistant sales manager. I never did work for the president of the company; a friend of mine did.

CS: What were some of the changes that you saw at the mill over the years, since you were there so long, starting from when it was locally owned?

BB: When I first went to work there we didn%u2019t get Thanksgiving as a holiday.

CS: Oh, you didn%u2019t?

BB: You know, that was hard because you always had Thanksgiving as a holiday when you went to school. They ran three eight-hour shifts, and eventually they went to twelve-hour shifts, which the other plants were doing. On that schedule you worked twelve-hour days. There was one group that worked Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, and I think they ran seven days a week; I can%u2019t swear to it. Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday--but one group worked four days one week, and then some groups worked three days. But the groups that worked three days, which was thirty-six hours, they paid them for forty hours. And I guess the ones that worked the four-day weeks got paid overtime.

CS: Do you remember what you started out making when you first worked there?

BB: It was less than two thousand dollars a year, I%u2019m sure.

CS: Yeah. So did you all live in town when you were raising your kids?

BB: Yeah, when we first were married. Right across from the plant there was a two-story house and we lived in two rooms upstairs. Then eventually we moved across the road in the one side of the house. A lot of those houses, people would live in one side and somebody else would live in the other side.

CS: Yeah, like a duplex. How was the area different then compared to how it is now?

BB: Well, we had a modern post office over there.

CS: Did you know most of your neighbors?

BB: Oh, yeah. I don%u2019t know anybody that lives in Lawndale now, but there%u2019s not nearly as many people live, because, as I say, a lot of those houses have been torn down.

CS: Were you surprised when the mills started closing?

BB: Well, a lot of the other plants had already closed, but I don%u2019t know. I was told that our plant was still making money, but the other Spartan plants were losing, so I don%u2019t really know. They were just like everybody else, borrowing money to stay afloat. That%u2019s the way a lot of people do. You know, they%u2019re encouraging people to try to keep their credit cards paid down.

CS: What kind of impact do you think that had on the area, with that many plants closing down?

BB: At that time the economy was good enough they could go somewhere else and find a job. [Pause] The town of Lawndale is incorporated and they have taxes, but they can%u2019t do much now because I think the mill%u2019s tax was about forty-something thousand dollars a year, and as I say, a lot of those houses aren%u2019t there any more. A friend of mine--she%u2019s dead now--their incomes were so low that you%u2019d get a discount at the tax office. Her income was very minimal, and I don%u2019t think her tax was but about ten or eleven dollars.

CS: Oh, wow. And you said you do have a son who lives nearby here?

BB: Yes, he lives about two miles on the other side of Lawndale, up on a road that%u2019s called Hicks Hill Road.

CS: What does he do?

BB: He works at a company called Purolator now, down below the old Wal-Mart plant down that road. I believe they make filters; I won%u2019t swear to it.

CS: Do you have any other memories of this area? Places that stood out to you, or traditions that you remember? Did y%u2019all ever go to the fair or things like that?

BB: Did you say the fair?

CS: Yeah.

BB: Not often. When the children come along we%u2019d go. But when I grew up we%u2019d go to the fair in Catawba County and you got to ride the merry-go-round one time; I think it was a dime. [Laughter]

CS: Did you miss living on the farm?

BB: Yeah, because that%u2019s out in the open. When we lived in Lawndale, the houses were about as--probably as close as the length of this room, and I always felt like I was cooped up. We bought what was supposed to be ten acres over here, and when they finally measured that I think it was seven-and-a-half, but the man didn%u2019t cut the price any. But at least you%u2019ve got more room. This man that lives above me is from Lawndale. So I know most of the people, even here.

CS: Did any of your brothers and sisters work for the mill?

BB: My youngest brother worked down here about six months or something.

CS: Oh, did he?

BB: He lives in Catawba County, but it was funny--there%u2019s a Morgan and Boggs, sort of well-to-do businessmen--I had heard that the Morgan is the one that bought the plant property. I hadn%u2019t heard it but a day or two and my brother called me. He%u2019d worked in the furniture place, and that had gotten to be about as bad as the cotton mills. My whole family called me Bob, and he called me and he said, %u201CBob, I heard that the mill had been bought and they were going to put a furniture manufacturing place in there.%u201D I said, %u201CWell, part of it%u2019s true and part of it%u2019s not.%u201D I said, %u201CIt has been sold, but there%u2019s no plans for a furniture manufacturer to go in there.%u201D You know, businesses, they can%u2019t afford to go into that kind of stuff now.

CS: Yeah, it%u2019s hard.

BB: Somebody came into Sunday school the other day and said--. Are we still recording?

CS: Um-hmm, you want me to pause it? [Recorder is turned off and then back on]

BB: A neighbor of mine--well, she%u2019s a friend of mine--she worked down at the plant too, and I visited her the other day. Her husband is pretty well handicapped, and of course she can%u2019t get out much; she just sits there with him. I said, %u201CYou know, several years ago you felt like teaching--education and health were about the only two vocations to get into that you stood a chance getting a job,%u201D and I said, %u201Cbut now, there%u2019s so many teachers getting laid off.%u201D

CS: That%u2019s true.

BB: She said, %u201CYeah.%u201D Somebody they knew had--and that goes back to the unruliness in the schools, as the parents are not parenting the children. When I worked down here there were some younger mothers there, and they come in every morning talking about what all they had done the night before, and they had children, school-age children. She said that somebody had told them that this daughter of theirs was a teacher, and I don%u2019t know when this happened, but she had a girl in her class that was such a disruption. One day the mother came to pick up the child for something, and the teacher followed her out and told her what an unruly child she was. She said, %u201CWell, you make her listen. That%u2019s what we pay you for,%u201D and that teacher quit teaching, they said.

CS: Really? Yeah. I bet it was a lot different when you were in school.

BB: Yes, you didn%u2019t peep. My daddy didn%u2019t tell me this, but I%u2019ve heard children say if they got a whipping at school and got home and their parents found it out, they whipped them again. I don%u2019t think there%u2019s anything wrong with whipping a child.

CS: How many kids were in your class when you were in school?

BB: I think we eventually graduated with eighteen in our class.

CS: Oh, really? Yeah, kids were a lot more respectful then, right?

BB: Yeah. Yeah, they sure are.

CS: Well, let me just ask you--. Oh, do you want to say--?

BB: No, but a lot of that is these single-parent homes.

CS: Let me ask you just a couple more, I guess, more personal questions about what would you say is one of the things you%u2019re proudest of, or one of your biggest accomplishments?

BB: The fact that I was able to work for fifty years.

CS: That%u2019s a long time. Most people don%u2019t have a job for that long.

BB: One of my sisters that was here a while back was working; she was past retirement. I said, %u201CIf you feel like it and they%u2019ll let you, go ahead,%u201D because it helps pass the time off. I know, they had been pressing the man I worked for at Spartanburg to ask me when I was going to retire, and I had told this man a certain date and then my husband died. I went and told him, and I said, %u201CHave you found anybody to replace me?%u201D He said, %u201CNo, you won%u2019t be replaced.%u201D See, they were cutting out positions everywhere, and I said, %u201CWell, let me work on through this winter because I can%u2019t stand%u201D--my husband died in May--I said, %u201CI can%u2019t stand sitting there in the house by myself this winter,%u201D and he let me work on. Then this Mr. Elder, who came in, the CEO came in there one day and asked me--he said, %u201CWhen are you going to retire?%u201D and I told him what I had said to (04:13). He said, %u201CYou will be replaced,%u201D and he said, %u201CYou can work as long as you want to.%u201D

CS: Do you miss working?

BB: Pardon?

CS: Do you miss it?

BB: Not after I quit. I miss the people. That was the thing of it because when you work with a lot of them for thirty or forty years, they were your second family, and they were so supportive of me when my husband died. In the meantime, [pause] I can%u2019t remember, along about that time I was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin%u2019s lymphoma, and I had six chemotherapy treatments and seventeen radiation treatments.

CS: Oh, my gosh.

BB: So, you know.

CS: They helped you, were supportive? Did your husband--was he still working when he passed away or had he retired?

BB: No, he had been retired a couple of years. He didn%u2019t like to work, and he always said he was going to retire when he got sixty-two, and he did, and I think he was about sixty-six when he died, so he got to enjoy a couple of years of retirement. But people that used to live up at an angle like that, her husband was a sales manager down there; she never did work, but he did. She told me after Bud died--she said, %u201CI can%u2019t stand to look down at your house because I can see Bud sitting on your porch all the time.%u201D

CS: Well, if you could give words of advice, what words of advice would you pass on to the next generation, to the younger generation?

BB: Try to treat everybody like you want to be treated, that%u2019s my motto.

CS: Okay. That%u2019s a good one.

BB: And get an education.

CS: Yeah.

BB: At least a high school. We%u2019ve got a little boy in our church that%u2019s quit school. I think he%u2019s about the tenth or eleventh grade. Kids like that just don%u2019t have a chance, but, there again, he%u2019s from a broken home, and [pause] I don%u2019t know what the solution is. How do you get a child interested in school?

CS: Yeah. If he%u2019s not being encouraged, it%u2019s hard.

BB: Well, that could be.

CS: Well, thank you, ma%u2019am. This was really helpful and interesting to me. Is there anything I didn%u2019t ask or anything else you want to say?

BB: No, I don%u2019t guess so. Would you like for me to ride with you over and let you see the plant?

CS: That would be nice, yeah.

END OF INTERVIEW

Mike Hamrick, November 16th, 2010

Born March 27, 1930, in Catawba County, Bobbie Bowman was one of ten children. The family lived on a farm near Jacob’s Fork River, where they raised cotton. Every fall the family would travel on a two-horse wagon for seventeen miles to Stamey’s Store in Fallston to buy school clothes; the trip took about two hours. Bowman states that the family had no electricity until she was about ten to twelve years old.

She and her husband, Harold “Bud” Bowman, moved to Lawndale and began working at Cleveland Mills in the 1950s, she in the office and Bud as a loom fixer. Her husband, now deceased, eventually went to work at J.P. Stevens for a higher salary and moved from loom fixer to supervisor.

The mill was originally called the Cleveland Mill and Power Company because it generated its own power and sold it to the residents. At first the mill simply made yarns, then made knit fabrics which were sold to Chrysler and Ford, and, finally, apparel knits, according to Bowman. Also in the early days, there were three eight-hour shifts, and employees worked five days a week; that changed eventually to 12-hour shifts and fewer days. Bowman mentions in the interview that in the early days employees did not get Thanksgiving Day off.

When the interviewer asked Bowman what she was proudest of in her life or what she considered to be her greatest accomplishment, she replied, “The fact that I was able to work for fifty years.”

Profile

Date of Birth: 03/27/1930

Location: Lawndale, NC