BOBBY HUNT

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 BOBBY HUNT

[Compiled November 18th, 2010]

Interviewee: BOBBY HUNT

Interviewer: Dwana Waugh

Interview Date: August 9th, 2010

Location: Shelby, North Carolina

Length: Approximately 81 minutes

DWANA WAUGH: This is Dwana Waugh. Today is August 9th, 2010. We are at Mr. Hunt%u2019s, Hunt%u2019s Auto Sales in Shelby, North Carolina, interviewing Mr. Bobby Hunt. Could you say when you were born and where you were born?

BOBBY HUNT: I was born in Rutherford County, 1945.

DW: Could you talk just a little bit about growing up in the area in Rutherford County and how you came to Shelby, or Cleveland County.

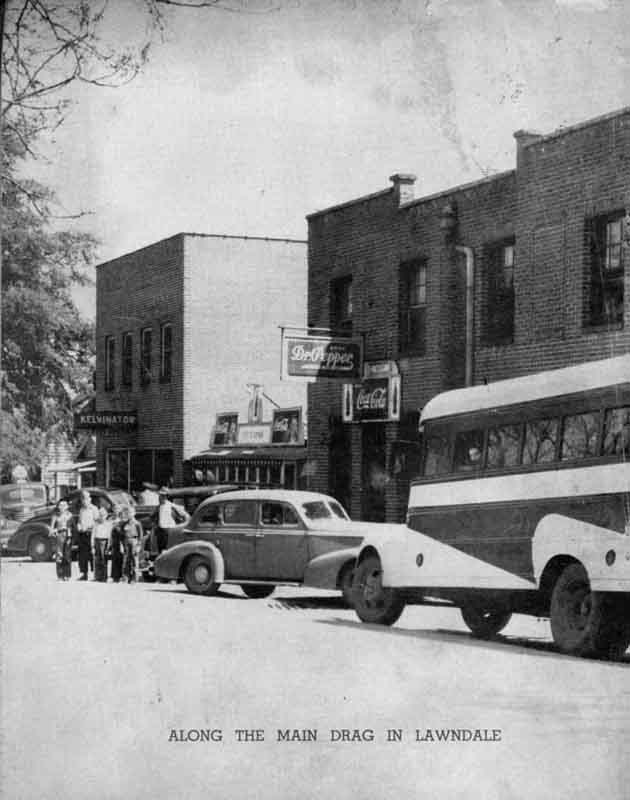

BH: Well, it was more or less sharecroppers. I was just a kid, so by the time I was old enough to know what was going on, then we moved back to Belwood, so my first five or six years of Belwood, then we moved to town and my whole life changed. We moved to town when I was about ten years old. I walked about two miles a day to go backwards and forward to school and catch the bus outside the city limits just to go back to Lawndale, to Douglas High in Lawndale, North Carolina. Times got a little harder and I got a little older, and I quit school and went to work.

DW: Okay. When you were talking about sharecropping, do you remember having to do a lot of the work on the farm?

BH: Sure, when I was ten years old I was getting up in the morning and plowing five or six acres of cotton and then catching the school bus.

DW: Oh. How early did you have to get up to--? [Laughter]

BH: [Laughter] Before daylight.

DW: Because five acres is a good amount.

BH: I was doing that when I was ten years old, really, so--and backing up a little bit, see, my parents separated when I was probably five years old, so I became the man of the house when I was ten years old.

DW: Do you have any brothers and sisters?

BH: Quite a few. Daddy had two families: eight in one family and nine in the other one.

DW: Ooh!

BH: [Laughter] So I%u2019ve got some brothers and sisters, that%u2019s for sure.

DW: And you were the oldest?

BH: The oldest brother, the oldest male.

DW: That%u2019s a lot of responsibility.

BH: Yes, there%u2019s four girls older than I am.

DW: So Douglas High, was that first through twelfth grade school?

BH: Yes.

DW: I can%u2019t imagine plowing five acres and having to walk.

BH: Well, you know, when you%u2019re ten years old you didn%u2019t realize it was work. Very little pay, so you just enjoyed doing it; didn%u2019t pay it much attention. And when you get off the bus, you get back on the tractor.

DW: Huh, yeah.

BH: I guess that%u2019s why I%u2019m not too smart today--never went to school much. Worked all my life, but if I had it to do again, I probably would do a little different, but I tried to live my life to where education never affected it that much.

DW: And speaking about education, how did you like going to Douglas? What was that experience like?

BH: Well, see, it was great; I didn%u2019t know any better, and that was all there was. It was kind of like, go to Shelby, and I really didn%u2019t want to go to Shelby, Cleveland School. I was a block-and-a-half from Cleveland School, so I could have went to Cleveland School, but I was born and raised in the country so I was still a country boy. Sixty years later, I%u2019m still a country boy. And I%u2019ve enjoyed my life, really have.

DW: Now, you were saying before, you were on the Green Line, and so you could have gone--?

BH: We lived--it was Green Line. It was just a name of a row of houses and the little street in Shelby. See, the next street down, they had a row of houses with all painted white, and that was White Line, or White Street. That was White Street; they called it White Street. Now, the hospital is doing some complexes in that spot. The area that I was in, all the houses was green, so they called it Green Line.

DW: Oh. [Laughter] Huh, okay. So you had a choice of going to Cleveland School or going to Douglas?

BH: Yes.

DW: Okay. I%u2019ve heard so many, I guess a lot of people I talk to had a lot of positive things to say about Cleveland and the marching band and the football team and the basketball teams. What made you decide to do Douglas? Was it that much more country of a feel?

BH: Country, the way I was raised, and those were the things I liked, and the people, you know. It%u2019s hard for a country boy to come to town and enjoy it for a while. He%u2019s not ready for town.

DW: [Laughter] So, with so many brothers and sisters, maybe home was the social place. [Laughter] What did you do, growing up, for fun?

BH: But it was almost like--see, when I actually started--when I was ten years old, that%u2019s really when my--a little before that--say, seven years old or somewhere around in there is when my parents separated, and that%u2019s when my father started his other family. But it was just eight of us moved to town, single parent, my mother and the rest of them.

DW: What kind of work did your mom do?

BH: More or less housekeeper because, see, we left the farm and there wasn%u2019t no ( ).

DW: So all eight went with your mom?

BH: We survived. I don%u2019t know how, but we survived. And see, when we came to town I was ten or eleven years old. I started doing odd jobs.

DW: What kind of odd jobs did you do?

BH: Well, I%u2019d get up at three o%u2019clock in the morning and worked at a barbecue stand and help prepare barbecue. I worked at Alston Bridges Barbecue. I remember making seven dollars a week, part-time.

DW: Was that good money?

BH: It was, well, you know.

DW: For the time?

BH: For the time, it was pretty good.

DW: So, at ten or eleven, you were [telephone ringing] and%u2026

BH: %u2026Working at the barbecue stand...

DW: %u2026going to school%u2026

BH: %u2026and then trying to go to school.

DW: Wow. So, I guess being the oldest son that you took on this role of being the male of the house and helping out.

BH: And that seven dollars helped feed the family.

DW: Yeah.

BH: Because there wasn%u2019t any such thing about blowing anything. You know, kids didn%u2019t blow money back then. Nobody ever blew any money because we never had enough to blow, so you just spent it where it was needed, brought it to the family; we all shared.

DW: And did your brothers and sisters [telephone ringing], your older sisters, work too?

BH: No, they all went to school. I%u2019m the only one that didn%u2019t go to school.

DW: Oh, yeah. Oh, wow, okay.

BH: Yeah, all of them went to school except me.

DW: Did they go to Douglas too, or did they choose to go to Cleveland?

BH: As long as they could go to Douglas, but they finally wound up going to Cleveland.

DW: You were saying some of your odd jobs were doing the barbecue. What other kinds of odd jobs did you do?

BH: I cut grass during the day and after school around town.

DW: Did you like going to school when you were in school?

BH: Well, I never have been an %u201CA%u201D student. [Laughter] But yes, I enjoyed it, but it only lasted until--see, I quit school when I was fifteen years old; I went to work fulltime. And I went to work at the service station that%u2019s still existing now; it%u2019s a pantry now; it%u2019s still there, and run the service station as a mechanic and whatever, servicing cars when I was fifteen years old.

DW: When did you get into cars and learning vehicles?

BH: See, when you grow up in the country you%u2019re born and raised with cars. We used to come to town, and we%u2019d come to town with my uncle. We%u2019d have three flat tires on the way to town, maybe one back, you know. [Laughter] It%u2019s a whole different ball game from today. You know, you carried a pump and you carried patches and boots to put in the tire. If it blow out you put a big boot in it. As long as it would roll, then that was all you had. [Laughter]

DW: Well, making it work. [Laughter]

BH: Making it work; you had to make it work. It was all you had and you didn%u2019t know any better. It wasn%u2019t nothing for five or six people to climb on the back of the truck and come to town once a month or once every other month. You know, if you came to town, that was something else.

DW: Would it be certain times that you would come?

BH: No, just when you ran out of everything you wasn%u2019t growing. You know, you grew your own meats, and you ate good because you raised your own chickens, you raised your own hogs, you raised your corn. You had to haul it to the mill to get your cornmeal, the wheat, so you raised about everything you needed except money, and you never could get it to grow.

DW: [Laughter] Whoever figures that out, [laughter] I need to find them.

BH: But you know, life, to talk about it, you say it was bad, but there was less people hungry then than they are today. Because if you ran out of something and your neighbor had it, you just go borrow it. When you got it back, you took it back. It wasn%u2019t nothing to go to your neighbor and borrow a cup of sugar.

DW: So what did you have to go to the store for?

BH: When you had some money. Otherwise, you toughed it out betwixt your neighbors, you know, that sort of thing.

DW: So, by the time your mother and your brothers and your sisters moved to Shelby, you didn%u2019t have the farm any more to eat off the land.

BH: Right.

DW: So how did that change?

BH: It was one of the main reasons I quit and went to work. That%u2019s really when I went fulltime. I think my first full-time job was thirty dollars a week.

DW: How many hours did you end up working?

BH: I don%u2019t know. A bunch, probably twelve, fourteen hours a week. I mean, a day, six days a week.

DW: That doesn%u2019t seem like much. [Laughter]

DW: Do you remember what your first job was?

BH: Well, after%u2026

DW: %u2026Full-time job.

BH: Full-time job was there at the service station. I went to work at the service station, and it was kind of a gift, more or less. As even today, all the things I do today, I hadn%u2019t been to school for any of it.

DW: You learned by doing. How did you learn about when jobs were open, and going about applying for jobs?

BH: You didn%u2019t have to apply for jobs back then. If you wanted to work and you sat down and talked to somebody--if you wanted to work, they%u2019d give you a chance. And I wanted to work; I needed to work; I had to work, so that wasn%u2019t a problem. [Laughter] Things have really changed as today as the way they were then.

DW: So there were a lot more job opportunities?

BH: Well, there wasn%u2019t that many jobs. It was just, I guess I kind of had a special gift. Everybody don%u2019t have the same gift. I%u2019m sixty-five years old, and ever since I was ten years old I%u2019ve never been out of a job.

DW: That%u2019s a blessing, yeah. That%u2019s a long working career too. [Laughter]

BH: I%u2019ve always said that if you want to work you can find something to do. I%u2019m a firm believer in that. I talk to a lot of kids now that are growing up and tell them they%u2019ve got to have a dream. If you truly have a dream, just work toward it; it will come.

DW: When you were younger, did you know what your dream was?

BH: It was things I always wanted to do. Kids then used to go by the trash dump and they%u2019d find a bicycle, and they pull it out of the trash dump, they take it home, and a couple of days later, they was riding it. That%u2019s the kind of things I started as I got older and it was garages and shops within walking distance of where I lived. You know, I was just a kid and that%u2019s where I hung out at. I%u2019ve never really been a sports fanatic. I would go hang around the garages and stuff. Yeah, and if I hung around and didn%u2019t get into any trouble, which I didn%u2019t, and wind up piddling and learning something, so that%u2019s the way I%u2019ve always done.

DW: Well, if I could go back just a little bit, when you were talking about growing everything back when you were living in Rutherford. Growing everything, what kinds of things would you eat? What was a typical meal that you might have for lunch or supper or dinner?

BH: It was nothing to have chicken for breakfast, chicken for dinner. It was just kind of whatever. You had corn and the canned stuff back then. You had your own warehouse, your own store because from one year to the next, you%u2019d can stuff and you ate what was in the--. Now, you%u2019d kill a hog and hang it out there in the building and you could eat off it all winter until it was time to kill again. Back then, they about knew what it would take, and then they made it go to the next winter because there wasn%u2019t any money. You had to raise it. Everybody raised two or three hogs, and if the neighbors didn%u2019t have much, then you gave them. You always give people--because if you needed something, then they give you--you share. I think that%u2019s where sharecropping came in at; everybody shared. You know, like if you got all your cotton hoed and all your corn pulled and your neighbors hadn%u2019t got theirs done, then you go help them.

DW: I guess around this time there were federal farm programs?

BH: If they did, I didn%u2019t know nothing about it. [Laughter]

DW: Okay. [Laughter]

BH: The landlord that owned everything, you shared with him and you done all the work. [Laughter]

DW: Oh, yeah.

BH: Naturally, somebody would have to dig his share. [Laughter] You%u2019d always just about get out of debt. The next year, you%u2019d get out of debt and clear some property. The next year, you%u2019d just about make it to this year. See, you went to the little grocery store. They wasn%u2019t pantries; they called them general stores, just a small, one-room building that you ran an account all winter. Then when the crops come in you paid your account. Well, you paid it to the landlord and the landlord paid your account. [Laughter]

DW: I%u2019m trying to figure out what I%u2019m going to ask next. [Laughter] So the debt, it was hard to ever get%u2026

BH: %u2026It was just like it is today. You know, we have credit cards now. It%u2019s always hard to pay them off, but it%u2019s our own fault. It%u2019s the way we live, but back then, when you don%u2019t have the control of the money whenever you do get a little bit, it%u2019s like you work for somebody and they pay all your bills, buying your basic what you need, and then at the end of the year, you%u2019ve worked hard, and at the end of the year what you do clear, he doesn%u2019t count it at how much you owe. He done already know how much you made, so it%u2019s real easy to say you didn%u2019t quite clear. Then you start off all over again the next year. Year in and year out, it%u2019s the same thing, but you really didn%u2019t have to have a whole lot of money because, you know--. It%u2019s a good learning experience. I guess it%u2019s one of the reasons why now I%u2019ve been able to survive off of so little. I think I%u2019ve done well.

DW: So when you were talking about coming into town and how rare that was to come into downtown Shelby, was going into town%u2026?

BH: %u2026Well, you didn%u2019t go shopping when you come to town. You knew where you was going to just one store that had a little bit more than the general store you had back in the country. You didn%u2019t ride around town and go shopping because you didn%u2019t have any money, so you just came to town to sightsee. See people you had never seen before, and you%u2019re riding down the street. You didn%u2019t know anything about being in bad shape because everybody you%u2019d pass, you%u2019d pass maybe two or three other people with flat tires on the road, or their vehicle quit on them or they run out of gas, so it was normal. Wasn%u2019t nothing big about none of it; that was just the way life was. Kind of like what you see on TV overseas now. That%u2019s the life that I%u2019ve had my share of.

DW: So what did you all do for clothes if there wasn%u2019t really shopping much?

BH: You probably got one pair of shoes a year, and maybe two pair of pants. If you cut them or wear a hole in them, they patched it. You know, it%u2019s kind of like, I pick at my grandbaby now, if she come in here with--buy pants with holes in them. Boy, that burns me up. If you had to do it; if you came in my day when that was all you had, you were ashamed to wear them until you get there and see--get to school and half the people there had holes in them, but because they couldn%u2019t do any better. It was all you had, you know. You didn%u2019t have but two pair of pants; you had to make them last you all year.

DW: Yeah, yeah, well--. [Laughter] So, after moving to Shelby and then getting your jobs and everything, did you miss living on the farm and being a sharecropper?

BH: Well, no, because you didn%u2019t have time. You%u2019re in the big city. [Laughter] And I was fifteen years old, and see, I got my driver%u2019s license when I was fifteen and started to work and started looking at girls. That%u2019s when the problems started.

DW: So I can get the time line right, you moved to Shelby when you were ten?

BH: Around ten years old.

DW: And started working pretty soon after you moved here, at Bridges Barbecue and doing other odd jobs?

BH: Barbecue and cutting grass and stuff like that.

DW: And then about five years after being here you quit school and started working full-time at the service station?

BH: Right.

DW: Did you stay at the service station a while?

BH: I stayed there about until I was [pause] eighteen and started driving a truck. I found another job driving a truck and making more money, a dollar and ninety cent an hour driving a truck.

DW: Was that the minimum wage at the time?

BH: There wasn%u2019t such a thing as minimum wage. [Laughter] There wasn%u2019t no set price; it was just whatever they was paying.

DW: [Laughter]

BH: Because, see, I was working at the service station, thirty dollars for six days. Long days, long hours, and then I went to work for a dollar-ninety cent an hour.

DW: And did you like working at the service station?

BH: Oh, it was a game to me because that%u2019s what I really, really enjoyed doing. I was really a mechanic when I was fifteen years old. I worked on peoples%u2019 cars all the time. I mean, it wasn%u2019t just changing oil and changing tires. We pretty much done everything: tuned up cars and fixed stuff, repaired stuff. When I left there and went to Shelby Concrete--no, I didn%u2019t, I went to Kings Mountain and came back to Shelby. I went to Kings Mountain, driving a truck, and stayed down there about two years for Bennett, breaking tile, hauling brick and making clay to build houses with. About a year or two at the most because then a man in Shelby--Shelby Concrete--it was one of the guys out there that talked me into coming by there and asking about a job. It was right at home and a little bit more money.

DW: More than the dollar ninety?

BH: Yeah.

DW: And this was a friend that told you about the job at Shelby Concrete?

BH: Yeah, some of the guys that were working out there, but I came back to Shelby Concrete. I don%u2019t really remember how long I worked there, but not very long. I had a friend that was working at the dock at Carolina Freight. I was about twenty, twenty-one years old, somewhere in there at this time, and he was working at the dock and I kept telling him I didn%u2019t want to work at the dock. I had a trip to Marion and the company took a load of concrete blocks and I stopped by there at Carolina and I took an application because they was hiring in the shop. I filled it out; it took about ten minutes to fill it out. They looked at it and interviewed me, and I went to work the next night on third shift at Carolina Freight, and I worked both jobs for two-and-a-half weeks, my old job and the Carolina Freight. Carolina was first shift and that was third shift.

DW: And this was at Shelby Concrete?

BH: Yeah.

DW: So you had five or six hours off a day, if that much?

BH: Barely, barely. When I was real young, like four or five years old, I stayed with my uncle a while, and they didn%u2019t come any tougher than he was. He would always say, %u201CIf you%u2019ve got something to do, go ahead and do it. You can eat and sleep on a rainy day.%u201D [Laughter]

DW: [Laughter]

BH: So I come close to doing a lot of that as I grew up in life, but I%u2019ve enjoyed it. When I went to work at Carolina Freight, oh, I was in heaven then. I was making, seems like, $2.40 an hour at Shelby at the concrete place, hauling concrete blocks, and I went to Carolina Freight, making $4.90. See, it more than doubled my salary.

DW: Did you think you would keep both jobs?

BH: Oh, no, no, no. I just wanted to be sure and I wanted to work them a notice. I%u2019ve always worked notices before I left anybody. And I wasn%u2019t sure that they was going to have me, but it worked great from day one. In order to keep a job, it%u2019s a couple of key things that I%u2019ve always done that people don%u2019t do this day. You don%u2019t have to know a whole lot; you don%u2019t have to work hard, but you do have to walk fast and look busy. That will keep you a job. [Laughter]

DW: I%u2019ll take that down. [Laughter]

BH: That will keep you a job [pause] if you look busy, walk fast. You don%u2019t drag from one point to the other one. You%u2019re always in a hurry and you always look busy.

DW: That helps.

BH: It helps; it really helps. Because for the last twenty-five years here, I%u2019ve had employees. I had employees here before I went to work here. But out of all the employees I have, the ones that I kept--one guy for eighteen years--he always walked fast and looked busy, so I never said anything to him, but you see somebody come to work dragging, well, how do you feel already? He%u2019s just not going to get it done today. He looks like he stayed out all night and feeling rough; he%u2019s not going to get the work done. But that%u2019s something I%u2019ve always done all my life. It really helped me through Carolina.

DW: Yeah, yeah. Well, if I could go back just a second--so, when you were working at the service station and then you went to work for Shelby Concrete, you were still working at the service station when you applied for the job?

BH: Yeah, I always--I never quit my job until I have a job.

DW: Okay.

BH: And then I always worked them a notice, whatever they required.

DW: Okay. And so, then they paid, Shelby Concrete paid better. What kind of work did you do at Shelby Concrete?

BH: Driving a truck.

DW: Okay. But not for building materials for houses, just concrete for--?

BH: Concrete blocks.

DW: Oh. Did you have to do any loading of the concrete blocks?

BH: No, see, at that time they had--the lift was on the truck. The cranes was made on the truck at that time, so they were self-loaders. You know, I operated all that, so that wasn%u2019t no problem. A lot of things I%u2019ve done over the years is kind of as a gift.

DW: Then, when you started working at Carolina, was this a job that a lot of blacks could get, or was this considered a really top-notch job to have if you were black?

BH: [Pause] I don%u2019t know of, maybe when I went there, I can%u2019t remember, it was maybe one or two in the shop when I went there. [Pause] It was quite a few when I left, but [pause] it was the best-paying job in this part of the country. See, it was a union job.

DW: And the other jobs were non-union?

BH: And still non-unions.

DW: How did you feel about working in a job with the union?

BH: Top shelf. Top shelf.

DW: Yeah.

BH: See, I was making as much money, making more money than school teachers.

DW: And teaching was one of the big jobs to have?

BH: Oh, yeah, that was the only type of jobs that most of--that was the real jobs.

DW: You mentioned unions--at least in North Carolina, it%u2019s been pretty difficult%u2026

BH: %u2026Very few%u2026

DW: %u2026for unions to organize. How did that work with Carolina Freight and workers and how the community perceived it being a union job?

BH: See, really, back then, unions helped, they helped a little on the equal rights. They helped a little on your mistakes that you made, like on-the-job mistakes. You kind of had somebody to speak for you on problems you would have, but I worked at Carolina Freight eighteen years and never was reprimanded for anything. I never had an accident.

DW: Was that a common thing to happen with workers?

BH: I%u2019ve seen guys lose their fingers. One of the guys I was working with on a different shift in the forklift department, right after I left, and I talked to him about it: a forklift fell on him and he got killed.

DW: Wow.

BH: I%u2019ve always tried to be safety conscious.

DW: Yeah. So it sounds like at Carolina Freight that they also took some precautions to make sure that work conditions were pretty safe.

BH: It was there, but it%u2019s ninety percent of accidents, ninety-five percent of accidents on all jobs is your fault.

DW: So I imagine the benefit of having a union is that you could have someone to stick up for you if there was an accident?

BH: Yeah, if there was an accident, and not only accidents--disagreements with something, that sort of stuff, then you had somebody to--. As long as you was right, then you had somebody to kind of stand with you. And it helped; I%u2019ve seen a lot of times it helped a lot of guys. That%u2019s the kind of things that I looked at all the time and that I see that it goes right back to what I say: ninety-five percent of the problems is you make them yourself. I worked at Carolina Freight five years, four months, and three days, and never punched in late, never left early, never missed a day.

DW: Five years and--?

BH: Three months, four days.

DW: So, what happened on the fifth year, third month, and--? [Laughter]

BH: I forgot to get my driver%u2019s--I should have went on to work. To this day, I say I should have went on to work. I forgot to get my driver%u2019s license renewed and I got stopped one night, speeding, going to work. The officer really didn%u2019t take me to jail, didn%u2019t do nothing except he stopped me to check my driver%u2019s license, and he said, %u201CYour license has been expired two months.%u201D I said, %u201CGosh, I didn%u2019t know it. I had plumb forgot it, officer.%u201D He said, %u201CI%u2019m going to give you a citation.%u201D He gave me a citation and walked off and left me, so what would you have done? Went to work or go home? I sat there for an hour and I went back home, but I called in. I mean, it wasn%u2019t no big deal. It was a big deal, but it messed up the track record.

DW: Was that the only time you were late?

BH: It was the only time I was ever late.

DW: That%u2019s impressive, yeah.

BH: Sure was.

DW: When you started, you said you were one of maybe a handful, a couple of blacks that worked for the company. What was that like? What was that experience like? Did it make a difference at all?

BH: Well, see, no, all of my life I%u2019ve worked with ninety percent of different nationalities other than the black race, because I started young and there wasn%u2019t older guys that had been there for years everywhere I had went. See, Carolina Freight was a little bit different. There%u2019s so many different departments when you went there. You could go as a tire man; you could go as a service man, this service, then you could go in the shop itself as a mechanic. That%u2019s why the service lane where they check oil and change tires, it was quite a few, but when you go on over in the garage part, then very few in number.

DW: So, working alongside people who weren%u2019t black wasn%u2019t a big issue?

BH: Never have, never have.

DW: Was there something that helped to bind you together as workers?

BH: Humble, you know. The boss man%u2019s never wrong. [Laughter] He might have three left shoes, but he%u2019s still never wrong. That%u2019s the problem we have today. You don%u2019t tell the owner and the supervisor he%u2019s wrong. You know, a whole lot of things, coming from the country, having it hard that you learn that you have to accept. It don%u2019t make it right, but you accept it and it makes survival out of it. Even today, but if I tell you about today, we%u2019d be done skipped over a bunch.

DW: That%u2019s fine; we can always come back.

BH: You know, I have people come by here that I%u2019ve done work for, and I ask them, %u201CWhen did I do this? I%u2019ve done forgot the car.%u201D %u201CTwo years ago, but so-and-so%u2019s happening,%u201D and if it%u2019s a couple-hour project or something, I%u2019ll go ahead and do it because I done it two or three years ago. It hasn%u2019t got nothing to do with this today, but those are the people that come back when it really needs work done that pay you. I%u2019ve never advertised here, very little advertising I%u2019ve done. I will take an ad if somebody hounds me about taking an ad, like a fish camp or something for a floor mat or something. As far as in the paper, I%u2019ve never advertised. Even the phone company: I%u2019ve never had other than my name in the phone book.

DW: So just loyal, building a loyal customer base? And this is a lesson you learned primarily through Carolina Freight or through your whole--?

BH: Through just the lifespan, yeah. You treat somebody right and they will come back.

DW: What I was going to ask was what kind of work did you do at Carolina Freight? You had mentioned that there were a lot of different departments, and I know earlier we had discussed about--.

BH: Well, in a four-year period, I went from one end of the shop to the other end of the shop, so, therefore, I was qualified to work in any part of the shop at any time. I don%u2019t know of anybody else that%u2019s ever said that they had done that. That was eighteen years.

DW: And before, you were saying it usually takes three years to--?

BH: To make first-class journeyman mechanic, which is a first-class. But, instead of picking up one class, then I picked up four or five.

DW: Yeah, in just one extra year. [Laughter] So, did you have a preference of what part of the plant you worked in?

BH: Not really, because actually, deep-down, see, I was working toward my dream but I didn%u2019t know what I was doing. I didn%u2019t realize that that%u2019s what that was all about, and at that time I didn%u2019t know that I wasn%u2019t ready to fulfill my dream. I was preparing myself for my dream even though I didn%u2019t know it. Yeah, if I hadn%u2019t of done what I%u2019d done, to work at one class at Carolina and quit and opened a business, I couldn%u2019t have made it.

DW: Well, I guess we should probably have that story. Before, you were saying it typically takes three years to become a first-class mechanic, but it took you four years, and you kept turning down raises so that you learned the company%u2026

BH: %u2026So I could move to a different department and learn that. And then, when I got the first phase of that, then see, that%u2019s ready for another raise. Actually, the three years was really from starting to top pay, so it kind of comes in phases. But they started me out doubling the money I was making everywhere else, so I wasn%u2019t worried about the money; I was worried about different things I could learn. That%u2019s where I got my air-conditioning and refrigeration from. Now I%u2019ve got a license for air-conditioning and refrigeration, and got paid to go to school for it. I used Carolina as a school.

DW: So when you went to each department you would be licensed in that department? You would get a license in that department?

BH: Well, you just pass your first class in that department, so if you ever needed it, then it ain%u2019t like a beginner. They%u2019d just give you a job and you knew how to do it, so it was kind of like it took you three years to learn that job. You could say it another way: back then, you could say it would take you three years from start pay to top pay. Which, all that was the same thing, but once you reached top pay, you should be able to do that job any time they needed you in that department.

DW: In top pay, was that a salary pay or it was still by the hour?

BH: It was still hourly.

DW: but at the top of the chart.

BH: Right.

DW: What led you to dream about opening your own business?

BH: Well, it was just the kind of life I had lived. I%u2019ve always wanted to own a little business and be able to support my family if I got married and that kind of stuff. It was just a dream that I%u2019ve always had, but that was back in my mind and I never realized I might be able to do it because of so many things I hadn%u2019t had to be able to do it. I guess that%u2019s the reason He led me through all of these things, so I%u2019ve always said since then that I%u2019ve learned these things over the years is be careful what you ask the Lord for, and I kid the Lord now about %u201CIf I%u2019d asked you for more, would you have gave me more?%u201D

DW: Yeah.

BH: But I%u2019ve never really went back and asked him for more. I said, no, I%u2019m not going to beg out of my life. [Laughter] It%u2019s a lot of truth in what I%u2019m saying. That%u2019s really kind of how this came about. He prepared me for it even though I had to work for it. He didn%u2019t just hand me nothing. I worked day and night for it.

DW: So you were still working at Carolina Freight when you started your shop here?

BH: I bought the shop before I even thought about quitting Carolina. Sure did. See, I was still preparing myself but I didn%u2019t know what I was doing. I always wanted a building, and actually, let me back up a little bit. I%u2019ll tell you how come I bought the shop. It was ten years before I bought this little ol%u2019 shop. I had built a thirty-by-thirty behind my house to piddle in, and worked on cars and stuff. One day my neighbor got drunk and he came down and fussed at me because he heard the air compressor running, so he was kind of bad to get lit up. He was as good a guy as any you want to have until he gets drunk, then something comes in his mind, so he hit me with it a couple of times. So, I told my wife, I said, %u201CI%u2019ve got to buy me a building somewhere else to piddle in,%u201D so I bought this little building out here away from the house. Down the road, five years later, I bought his house too. [Laughter]

DW: That%u2019ll teach him to complain! [Laughter]

BH: [Laughter] But I mean, this sounds like it%u2019s not real, but it%u2019s really what happened. But see, I still didn%u2019t realize why I bought this building other than I just wanted somewhere to piddle away from home. After I bought it I got scared. I bought it in the wrong location.

DW: What do you mean?

BH: This is an all-white community.

DW: So this was a shop before you bought it?

BH: Yeah, it was a little shop. It was a white guy that had it; he outgrew it. But it%u2019s in an all-white community. But I couldn%u2019t have asked and couldn%u2019t have bought a place in no better community. I%u2019ve worked for everybody in this community. I%u2019ve done work over the years for everybody in this community. They%u2019ve treated me--I couldn%u2019t ask for any better. As a matter of fact, this eye surgery, I guess I%u2019ve had a call from everybody in this community.

DW: That%u2019s great, yeah. That%u2019s great.

BH: I mean, just from a little eye surgery.

DW: Yeah. So how did you come across this land?

BH: Well, even though I worked at Carolina Freight, that wasn%u2019t the only job I had. See, I still worked with people I knew, like there was a city policeman I used to help some part time while I was at Carolina Freight. He tore down houses and moved stuff. See, I drive bulldozers and all that kind of stuff, so I already knew how to do that from back when I was working at the brickyard, see, and I drove trucks and I%u2019ve had a chauffeur%u2019s license ever since I was eighteen years old. So while I was working at Carolina Freight, I done that on the side; it helped me on the side.

DW: Was that out of necessity or did you just%u2026

BH: %u2026No, no, no%u2026

DW: %u2026enjoy the work?

BH: Enjoyed the work. Work didn%u2019t bother me, and my wife was working too, so we both was working. I used to, along for twenty-five, twenty-six years or right in that range, I started building dragsters, and I used to race cars, drag cars. I%u2019ve even drove it to work during the week, and on a Saturday, Friday night, I%u2019d start changing it over to drag it on Sunday. [Laughter] So it wasn%u2019t like it is now.

DW: Where would you do the drag racing?

BH: We had a dragstrip out here at Shelby and then one in Boiling Springs.

DW: So are you a NASCAR--?

BH: No, I wasn%u2019t no NASCAR, just kind of hometown dragstrips. I done that until my first kid--well, my second kid. My daughter was two or three years old at that time when I quit drag racing. Even my wife, she%u2019s a country girl too. We used to ride motorcycles back when we first got married, both on Harleys, so I%u2019ve lived a good life, an enjoyable life. But I%u2019ve tried to live a good, safe life. I%u2019ve put family first. I%u2019ve always tried to put my family first, and I think that%u2019s the reason the Lord%u2019s blessed me so much. Every day, I have to thank him. I don%u2019t see how I%u2019ve done what I%u2019ve done. I%u2019ve done a whole lot of stuff that%u2019s not even nowhere near we%u2019ve even mentioned. It ain%u2019t on none of those things that other people--that%u2019s what other people saw.

DW: In terms of work or outside of work?

BH: My wife has a soft heart, as I do myself, and we%u2019ve kept families together; we%u2019ve donated money to families; we%u2019ve donated cars to families; we%u2019ve started a senior group at the church. We%u2019ll take thirty people and say, %u201CWe%u2019re going to go to the mountains.%u201D I%u2019d rent vans and haul the seniors to the mountains. They%u2019d cook cakes and pies and fix sandwiches. We have the best ol%u2019 times.

DW: What do you think led to you and your wife being so giving in that kind of a way? I guess I%u2019m wondering is had you experienced someone doing the same kinds of things for you, or was this just tied to your faith?

BH: [Pause] I guess it was tied, more or less, to the way I was raised. We helped one another, and you just don%u2019t see that any more. And I was being blessed so much, I didn%u2019t understand where it was coming from.

DW: To whom much is given, much is required.

BH: You sound like a Baptist.

DW: I am. [Laughter] Trying to be a good one. So when you got the shop, was it the same buildings?

BH: It had two doors and one office in there, and all just a square building.

DW: Just a square building? And then you added on, obviously.

BH: I added that room on over there, and then I went and added four rooms on the back, and then ten or twelve years ago I come back and added this office. No, I added that office in there first about fifteen years ago, and then about ten or twelve years ago--I went through about fifteen years of things going great, and the last five years, this economy has been falling for five years. The bottom fell out of it two and a half years ago, but I knew it was coming. I%u2019ve had as many as seventy cars on this lot, so many that I had to have out yonder beside the road full of cars when things was really booming. Three years ago, things started to tighten up. Three years ago, and I could see it then. I%u2019ve always had just a little bit of insight of this economy deal because, see, one month they say, %u201CSend me customers.%u201D The banks in town would call and they would say, %u201CSend me some customers. Send me some people that need financing on the cars,%u201D and all this kind of stuff. Two months later, you send a good customer and they get turned down, and that%u2019s the way the change starts, from the people with real money cuts their money first. If you%u2019ll watch the people with real money, when they start cutting, you need to start looking around to see what%u2019s going on. But it%u2019s went from that a year ago the loan sharks won%u2019t even finance on a real car now, and that%u2019s people with twenty-eight percent interest. So it took me about a year to sell everything to get out of debt. As I say, at that time I was thinking about well, I%u2019ll just retire. And I really would have when I retired a year and a half ago. When my wife got sick, I had really signed up for retirement and everything until my daughter walked in and quit her job, and, see, that caused another problem. Now there%u2019s another one on the books that%u2019s got to be fed--and two girls, see. So if I quit, they won%u2019t have a job. But it wasn%u2019t time for me to quit because I%u2019m still young enough in mind to where if I quit, I%u2019d have got in trouble, and I knew that.

DW: I was going to ask if you%u2019d been working fifty-five years to get lazy. Would you really retire?

BH: No, no, no. See, I%u2019d have started back to loafing and an idle mind. I%u2019ve always liked girls, so that%u2019s why I--. But as you get older, you learn to control your mind and don%u2019t believe everything your eyes see. But you learn to control yourself a lot better. It%u2019s never a hundred percent, but you learn enough to keep you out of most trouble. But that%u2019s kind of how life is, and that%u2019s the way I%u2019ve made it.

DW: So I guess when the company was really doing--when you first started you had said earlier about loyalty and you didn%u2019t need to advertise, kind of word-of-mouth, do you remember your first customers?

BH: Pretty much. I%u2019ve never got paid for it.

DW: [Laughter]

BH: In the beginning, you know your friends, that%u2019s kind of how you get started, people you know. Yeah, my first customer, first two or three--well, maybe not the first two or three--I know the first customer, what I call the real job when you do a car all over, when you get it and sand it down and paint it all over. I%u2019ve never got paid for it yet.

DW: And how long have you been open? [Laughter]

BH: A long time. Twenty-nine years, somewhere right in there. I quit counting.

DW: Yeah.

BH: But overall, I knew and I told myself when I quit Carolina, even though I had over the years prior to quitting, I had probably sixty percent of the tools I needed to open. But you know, as you open and go into work, then you%u2019re continuously buying all the time, still buying tools all the time because things change and you keep adding what you need.

DW: So while you were still working with Carolina, that helped you build up your customers?

BH: Everybody that I got that I worked with would come by for repair work because they wanted to see how crazy I was for quitting making money to come not make any money, but I toughed it out and it really took about five years. I tell everybody now, when you go into business, the first five years are going to make you or break you.

DW: Yeah.

BH: But you%u2019ve got to be able to at least fund yourself for at least two, two and a half years and not make any profit. After that, it should start making profit. It should break even to where you can live, but not what you say getting a salary for about four years, and then after that it should start seeing something. If you don%u2019t see nothing by then, to where it%u2019s growing slowly--and I%u2019ve never liked a rapid growth--it%u2019s dangerous in most businesses; I%u2019ll put it that way.

DW: So have you ever thought about moving from this location since you%u2019ve been here?

BH: I%u2019ve never desired to have anything bigger, and I%u2019ve had all kinds of offers. I%u2019ve even been offered grants and turn them down to expand. It goes kind of right back to why would I need a big building out on the bypass? Who%u2019s going to run it? Several times I%u2019ve said today is why would you want something you can%u2019t handle? So I%u2019ve learned if you talk to the Lord about it, let him lead you, you might not like it, but in the long run, you%u2019ll come out better.

DW: Well, this may seem like a silly question because you own your own business and are invested, but did you have any job that was your favorite or the best job you%u2019ve worked?

BH: I%u2019ve pretty much enjoyed my life in all the jobs that I done because all of them was a learning experience and it%u2019s kind of like now, I%u2019ve got five classes of driver%u2019s licenses. Anything out there on the road, I can drive it, I%u2019m licensed for it. That just didn%u2019t happen overnight, so all those jobs and projects and stuff are things I%u2019ve learned over the years.

DW: Yeah. Did you ever have any desire to do something that wasn%u2019t in the mechanical field?

BH: Backing up a little bit, yes, I%u2019ve always enjoyed drag racing, but I mentioned a while ago, when I had my second kid, when he got about a year and a half, two years old, I looked at him one day and I said, %u201CIf I stay in this, me and him both will be hungry the rest of our lives.%u201D My last run was out here at Shelby. I took my class and a class above me. I had seventy-two trophies setting at home and no money. I haven%u2019t been back to a track since, and that%u2019s been fifteen, eighteen years. And I would have, because as things grow, expenses grow, you know. Those boys have a quarter of a million dollars in a car now.

DW: Did you drive different vehicles or did you have one?

BH: I just had the one.

DW: Did you have a name for her?

BH: No. Half the people back then would gang up and help each other. They%u2019d build something that would run this weekend and something that would run if they tear it up, and they%u2019d go build it back during the week and go fix it.

DW: And the races were happening on Saturdays?

BH: Saturdays and Sundays. You know, as I got older I realized what I was missing out. One day when I was, really, if I%u2019m not mistaken, I was twenty-nine years old, and I would always go to church; I%u2019ve always went to church. A fellow invited me to church. That%u2019s why I go to church. He said, %u201CHave you been baptized?%u201D I said, %u201CNo, not really.%u201D He said, %u201CWhy don%u2019t you be baptized?%u201D I said, %u201CWell, I%u2019m not quite ready. I%u2019ve got some more things I want to do to help me get ready,%u201D and he says, %u201CYou%u2019ll never be ready if you wait to get it done to get ready, because you can%u2019t make yourself ready.%u201D You know, I thought about that. I thought about that and thought about that, and I think a couple of weeks after, I was asking the Lord, %u201CWhat was he talking about?%u201D He never did give me an answer, but anyway, he told me enough for me to understand that without the Lord, I can%u2019t do nothing. It just come to me that plain and simple, so I was baptized, and later on, joined the church--trustee off and on for the last twenty years.

DW: Have you gone to the same church?

BH: Pretty much, pretty much.

DW: Okay.

BH: But as a kid I was a Methodist, and, see, I wasn%u2019t baptized, I was sprinkled. That was the reason--I%u2019ve always been in church, but never whole-hearted, so I decided I wanted to be baptized.

DW: Did you to go to%u2026

BH: %u2026Mt. Calvary%u2026

DW: %u2026before, when you were younger?

BH: Brooks Chapel.

DW: In Rutherford?

BH: Rutherford. It%u2019s on the Rutherford County Line, but that%u2019s--yeah, I%u2019d say Rutherford.

DW: Is it still there?

BH: It%u2019s still there, and, as a matter of fact, the minister right down the street is pastoring up there.

DW: Oh.

BH: I%u2019ve done all of his work for years. [Telephone ringing]

DW: I was going to ask about social things and what kind of social activities you did, but it sounds like the drag races were kind of your off time when you had off time. Did you ever go to the park or things of that nature much?

BH: Not often. I%u2019ve never been much for sports. I guess that%u2019s why my son was a fanatic. I kept him into something from the time he was old enough until he went to college, and in six years of college he was an athletic trainer because I guess I never was in sports much. I%u2019d go see him; he played football. He was one of Crest%u2019s state champions.

DW: Oh, okay. In football?

BH: In football. I finally pounded in his head he could forget ever going into a future in football because he was about a hundred-and-forty pounds. [Laughter] And shorter than I am. He still stayed in sports; he was an athletic trainer. He went to Mars Hill six years and come out and he worked with the Atlanta Falcons a year and come back to Clemson, South Carolina, and he realized that it really wasn%u2019t what he really wanted. He joined the Army. He joined the Army, went to Alaska for about a year and left there and went to Iraq for eighteen months, come back and went to Texas for a couple of months. All this is in the Army. He%u2019s still in the Army now, and now he%u2019s putting on casts in Fort Knox.

DW: Was that ever an option for you to go into the military?

BH: No, I%u2019ve got a handicap too.

DW: Oh.

BH: My left hand was cut off when I was eighteen months old, and they didn%u2019t know how to put it back on.

DW: No.

BH: Yes.

DW: How did that happen?

BH: I fell on a milk bottle. See, they didn%u2019t have plastic bottles back then; everything was glass. I dropped the bottle, it broke, and I fell on it and cut my hand off.

DW: Oh, wow.

BH: So, all that%u2019s good; I don%u2019t remember it. They say I was eighteen months old. I%u2019ve learned to live with it and I don%u2019t pay it any attention. When I reach for something, it knows what it can pick up, so it%u2019s not going to go after it if it can%u2019t bring it back.

DW: Now that%u2019s really amazing because you have to work with your hands a lot.

BH: Yeah, it is. If that%u2019s all your hands know, they know what they can and can%u2019t do, so when you reach for something, it%u2019s not going to reach for it if it can%u2019t do it, so the right one always takes up the slack. [Laughter]

DW: I guess one of the last questions I%u2019ll ask you is how have you seen Cleveland County change in your lifetime? And then, I guess, to piggyback off that, what do you think were the biggest changes, if any, that have happened?

BH: I%u2019ve enjoyed it. I wouldn%u2019t have it any other place. I wouldn%u2019t think about moving to any other town. I%u2019ve had a great life here. Everybody has been good to me here. As a matter of fact, I know they%u2019re great because I guess I speed more than anybody in Shelby, but I guess the Lord rides with me a lot, and I haven%u2019t had a speeding ticket in twenty-five years. I%u2019m just saying that I%u2019m lucky and great to be in this town. I wouldn%u2019t trade it for any other town I%u2019ve ever been in, even Vegas, and I%u2019ve been to Vegas.

DW: Yeah, that%u2019s good.

BH: I don%u2019t know of anything really bad that I would down this town on. Times, [telephone ringing] as it is now, I don%u2019t really see there%u2019s nothing I can complain about. It%u2019s really been good.

DW: Is it very drastically different than the Cleveland County you remember at ten years old?

BH: Oh, gosh, yeah. They wouldn%u2019t let me drive a truck to town to the Cleveland Mill over there now if I was ten years old like I%u2019ve done then. [Laughter]

DW: Yeah. [Laughter]

BH: So, yeah, it%u2019s made a lot of changes, but I think all for the better. [Pause] Everybody has been good to me. I don%u2019t want to brag too much, but everybody%u2019s been good to me.

DW: I don%u2019t know if it%u2019s bragging.

BH: Sometimes I think that people think more of me than I do of myself in this town. I%u2019ve had dealings with quite a few people in this town. It%u2019s not fair to say that from the beginning until this day, sixty-five to seventy percent of my business has been other people. I couldn%u2019t have made it without them, so they%u2019ve been good to me. My people have been good to me too. Maybe they just didn%u2019t have the money to spend.

DW: I guess I%u2019ll just ask if there%u2019s anything I didn%u2019t ask or we didn%u2019t talk about that if someone comes to this interview fifty years from now, what would you want them to know about you, your life, or Cleveland County or your business?

BH: I still say and I%u2019ll say again that anybody that opens up a business, if you%u2019ll treat the public the way you want to be treated, you%u2019ll probably survive; you%u2019ve got a better chance of surviving. You see that sign up there?

DW: Um-hmm. All returned checks?

BH: No, the other one.

DW: Oh.

BH: That%u2019s the one right there.

DW: Oh, Cleveland--?

BH: No, there%u2019s another one up there. Oh, she moved it. It%u2019s outside that door.

DW: Oh, okay. [Reading sign] It%u2019s good to be a Christian and know it but it%u2019s better to be a Christian and show it. Yeah.

BH: There%u2019s a sign out there that says %u201CHelp me resist temptation, oh Lord, especially when I know anybody looking.%u201D

DW: Yeah, that can be when it%u2019s the hardest. [Laughter]

BH: That%u2019s when it%u2019s the hardest. You know, you don%u2019t have to brag; you don%u2019t have to say anything. If you live the life of that card, you%u2019ll survive.

DW: Yeah, well, thank you. I appreciate your time in doing this.

END OF INTERVIEW

Transcribed by Mike Hamrick, November 18th, 2010

Edited by Shannon Blackley, June 12, 2011

Sound quality: good, although interviewee speaks softly

Bobby Hunt was born into a sharecropping family in Rutherford County in 1945. He moved to Belwood, N.C., and recalled plowing five or six acres of cotton in a morning before he caught the bus to school. His parents separated when he was five or six years old, and he said his father had “another family” of nine children besides the eight he had with Hunt’s mother. Hunt was the eldest boy in his family. He moved to Shelby when he was 10 years old with his mother and siblings. He lived in “The Green Line” row of houses and attended Douglas High School in Lawndale, N.C.

One of his first paying jobs was at Alston Bridges Barbeque making $2 a week. He drove a truck for two years, worked for Shelby Concrete, and then Carolina Freight, where he worked in all the different departments of the shop for 18 years. Hunt quit school when he was 15 to go to work to help support his family, but he said he “used Carolina Freight as a school” to develop his automotive skills, driving trucks, and heavy equipment and working as a mechanic.

Later during his time at Carolina Freight, he bought a small building and started his own business, Hunt’s Auto Sales, which is still currently in business.

He also raced cars and built dragsters. He said the people of Cleveland County have been good to him and, “…if you treat the public the way you want to be treated, you’ll survive.” He said he “wouldn’t trade Shelby for Vegas.”

Profile

Date of Birth: 04/01/1921

Location: Shelby, NC