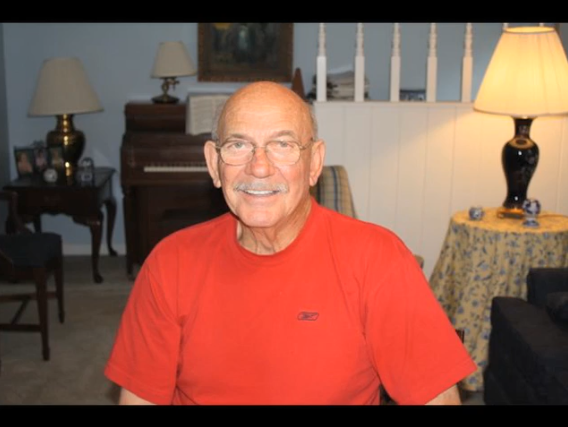

BUZZ BIGGERSTAFF

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 BUZZ BIGGERSTAFF

[Compiled October 4th, 2010]

Interviewee: BUZZ BIGGERSTAFF

Interviewer: Carter Sickels

Interview Date: August 4th, 2010

Location: Boiling Springs, North Carolina.

Length: Approximately 51 minutes

CARTER SICKELS: This is Carter Sickels, August 4th, 2010, interviewing Buzz Biggerstaff at his house in Boiling Springs. Do you want to say your name, place and date of birth?

BUZZ BIGGERSTAFF: Buzz Biggerstaff, 12/5/37.

CS: Okay, good. Where were you born?

BB: In Rutherford County.

CS: Okay.

BB: Cliffside.

CS: Okay. [Microphone noise] And that%u2019s--where is Cliffside?

BB: Cliffside is west of here about six miles.

CS: Okay. Were your parents from here, or from there?

BB: They were from the general area. My dad was from up the road a couple of miles, and my mom was over in the Goode%u2019s Creek section, which was three or four miles the other way, so, yeah, they were there. The family on my mom%u2019s side was next-door-neighbors to the men, or the gentleman that built the first plant.

CS: Oh, okay.

BB: So he left the farm and went with him to help build a plant, so Mom and the kids all moved on the village while it was being built.

CS: Oh, so your father worked on the--?

BB: My father, he was in the spinning room, and was what they called a section man. He fixed the frames, and they had changed the size rings that were on the machines that determined the bobbin build and the travelers. They had to take care of those and record when they were put in and when they were taken out and the cycle time and all. Then, when he got in his mid-twenties, he had an opportunity to begin barbering.

CS: Oh, okay.

BB: So, in the town there as well, so when he and Mom got married, he was a barber and continued that until he passed away.

CS: Okay.

BB: I think it was thirty-five years he was a barber, so he spent a good bit of his early time in the plant, but then after he became a barber he never did go back.

CS: Yeah.

BB: Then she was a spinner in the plant, and when they got married, she quit and never did go back to work, except that only with eight kids.

CS: Eight kids? Wow.

BB: Eight kids, yeah.

CS: So you grew up in the village?

BB: I grew up--the first year--I was born there on the village, right in the middle of town. Our home was there, behind the Memorial Building. When I was about one, they had a chance to move out in the country. It was just a couple of miles out in the country. Dad liked to garden, and he liked to keep cows and chickens and hogs and stuff, so that gave him the opportunity to do that, so we lived there nine years, and then, when I was about ten, we moved to the last house that we lived in before Dad passed away. It was up near the school, but it was about a half a mile out kind of by itself, so it was in the country too, you might as well say.

CS: Did you also have cows and--?

BB: Yeah%u2026

CS: %u2026chickens and stuff?

BB: We always had one; we had a mule to plow the garden, and we had chickens, both for laying and Sunday dinners. We had the pork. We had usually a couple of hogs, and we had them both for bearing piglets and also for eating, the big boys. So, yeah, we had chickens, hogs, mule and cows, pretty much, out there, and a good-sized garden. I mean several acres.

CS: Okay, that%u2019s nice.

BB: Yeah, yeah. [Laughter]

CS: When did you start your jobs? When did you start working at the mill?

BB: I worked in the summer, when I was still in high school, and I was about seventeen. Then, the next year, we got married and I continued to work until time for school to start, and when it started, I quit and Beth went to work. I got through the first year at Gardner-Webb, and I determined that we needed a little bit more bread coming in, so I went to work on the night shift, the third shift. They called it the graveyard shift. I went to school six days a week, and we were working six days a week, so we pretty well were occupied all the time. When you%u2019d catch an hour of sleep, it felt good.

CS: I bet. So, the mill you were working at was Cliffside? Was that the name of the mill?

BB: It was the Cliffside Plant of Cone Mills--C-O-N-E--Corporation.

CS: Okay. Wow, how did you do that? [Laughter] How did you sleep?

BB: Well, it wasn%u2019t easy. We had the, let%u2019s see, the first child was born in %u201961, and I graduated from Wofford in %u201961. So as soon as I graduated, they offered me an opportunity of going on a management training. So, after two years at Gardner-Webb and two years at Wofford, doing the third shift number and six days a week and all with both, then after our first child was born was about the time they offered me the chance to go to training on management. So I didn%u2019t complete that until they had an opening in the finishing department, a department head job. So I went from what you might as well say my first training was after I had been there a while, my first job was in industrial engineering, and I hadn%u2019t had any supervision type experience at all, but this department head job came open. At that time, nobody except the plant manager was a college graduate, so I guess that was one reason they offered me that job. So I took it and remained on it almost twenty-five years.

CS: Oh, wow.

BB: And was moved to another department, and later, as I got older, they moved me back to industrial engineering, which worked out real good. I didn%u2019t have to worry about somebody calling me at three o%u2019clock in the morning and wanting to know how to get a machine back running and this kind of thing. So I finished up--my last seven or eight years was back in industrial engineering.

CS: Okay. What kind of work, like, what kind of work would that entail?

BB: Industrial engineering, we%u2019d primarily set rates and study jobs, and in the most recent years, the last years that I was there, ergonomics became a big thing. Part of our responsibility was studying jobs, seeing how we could improve the job and make it more person-friendly. That was a real interesting part of the job too.

CS: That is interesting.

BB: We primarily set rates. We studied the jobs to determine job loads, and then we worked under the area of ergonomics to try to improve how everything was done.

CS: Okay. So those would have been what years?

BB: When I went into the department manager job, it was in--well, by the time I went through the training and worked in industrial engineering a while, the job and finishing, I went on in %u201964. I kept it until %u201988, and then for one year I was the department manager of preparation, and then they decided they wanted to have me back in industrial engineering. So the last seven years or eight years, I worked in that area until I had some heart attacks and didn%u2019t get to work any more. But, it was actually forty-two, forty-three years of straight working, and then, after I had my heart attacks I went on disability for the last two years. We could do that and still remain on the payroll and get full benefits, but as it ended up, I had a total of forty-five years.

CS: Okay. Wow. When you were in the management position, the industrial, did you still have--did you have a lot of contact with the other employees like weavers and spinners?

BB: Oh, yeah, yeah. Yeah, and I think, Carter, that one reason they wanted me to go into the management end, the department head of finishing, is because I had majored in psychology and sociology, and you know what that entails. The first department I had, had two-hundred-and-fifty employees, and two-hundred-and-twenty of them were female.

CS: Okay.

BB: A lot of people, you know, they can%u2019t handle the opposite sex; the women can%u2019t handle the men, and vice-versa, but it was right down my alley. I enjoyed doing it. I had additional training experience to learn all the operations, and it took a little while to do that. I tried to get everybody on my side--show me the right way, and then after I learned the right way, I didn%u2019t need to run a job--I just needed to know if it was being run correctly.

CS: Right.

BB: So I went on those premises of trying to learn the correct way to do anything, and then see that it got done. Later on, we converted to another product and I didn%u2019t have quite that many people. I had, I think the peak was, like, a hundred-and-fifty when we went to another product.

CS: Okay.

BB: It didn%u2019t take as many people.

CS: Were the jobs sort of divided between what kinds of jobs the women did and what kind of jobs the men did?

BB: The original work was primarily sewing machine type jobs. Part of them--we made towels and washcloths and beach towels, and part of them had a fringe-end. I know you know what I%u2019m talking about with a fringe-end. So we had women that ran the cutters that did that.

CS: Okay.

BB: The end-hem towels that had to be end-hemmed, folded and end-hemmed, we had all women that did that, the cutting of those towels. Then the next process was the sewing and the labeling, and the women were a lot better at doing that, so they were on all the machines. That was the reason I had so many more of the women than I did men. The men did primarily fixing, getting the machines back running, and service-type jobs. The men would have to move seventy-five or a hundred pounds of a product that the women couldn%u2019t handle, most of them. Some could, but most of them couldn%u2019t, so that was pretty well the way that was.

CS: Okay.

BB: And then, when we converted to denim, it was about that same ratio even though, except for inspecting the fabric, both women and men ran the roll-up machines. We had to put the roll back in the--I mean, the inspected fabric back in the roll and could be shipped to our customer. Men and women did that job, equally as well. Both were good at it.

CS: I know, like way back, probably much before you started working there, it was mostly white men and women who worked there--well, in a lot of the mills.

BB: Yeah, it was primarily the white, but we did have a section in town that the Afro-Americans lived in, and they did some different jobs. The plant and village plumber was an Afro-American, and he, in turn, trained another one that worked in the private sector. The man that ran the hardware, he sold plumbing products, and some of the folks on the village used him. Then, later on, the fixing became a reality, and also some supervision, but the most of them worked in service type jobs like handling bales of cotton, loading and unloading it.

CS: Okay. Especially since you were more on the management side, do you remember there being any kind of issues with people feeling unsatisfied, or wanting to organize and have unions?

BB: They didn%u2019t talk about unions. There was a time before I came along, in the twenties, late twenties, that they tried to organize plants in the county, and they were turned away. They didn%u2019t get to do it. And even though you would have some people that would talk it, they were the kinds that were really undesirable. They did a good enough job that you couldn%u2019t just fire them, you know, because of them being with the attitude that they had. I don%u2019t mean because they were wanting unions. They were just generally negative in a lot of things. And even though you had some of those, the majority was satisfied with their work and their amount of work, and also their pay. They were happy with their pay and all, so as a result, we didn%u2019t have to worry too much about unions. We had them a couple of times coming and trying to get information. They had to stay out in the street--they couldn%u2019t just--in so many feet of the gates, which is pretty much the same now, but they didn%u2019t get to first base with it. After hanging around a few days, they realized they were barking up the wrong tree, so to speak, so they got out and left.

CS: What do you think the difference was about here in Cleveland County versus, is it Gastonia where there was such an uproar?

BB: Yeah, Gastonia was--I don%u2019t know. When I was coming along--and not being disrespectful to Gastonia and Gaston County--I%u2019ve got some relatives and I%u2019ve got some real good friends that live there, but I can remember, coming along, that they would talk about a murder in Gastonia. You wouldn%u2019t hear of one, very rarely, in Cleveland County, Shelby, or the area that I grew up in. So they were, a lot of those people down there were the hotheads. They got mad and shot each other and all that good stuff. I remember, my wife, Beth, talking about her grandparents on one side of the family who lived in Mt. Holly. So, to get to Mt. Holly, you had to go through Gastonia, and at that time, (Interstate) 85 wasn%u2019t there, and you had to go through the middle of town. They got detoured because they were investigating a murder on the main street there.

CS: Wow.

BB: It used to be, you know, you%u2019d hear of it%u2026

CS: %u2026It was just a rougher%u2026?

BB: %u2026right much. And, of course, it%u2019s gotten too bad everywhere now. You just didn%u2019t hear of that kind of thing here, and I think that was one of the big reasons that the union was trying so much to get in down there.

CS: Okay. Who were the owners of the Cliffside mill? Were they local?

BB: Mr. Hanes, as I mentioned, came from a farm over in the Goode%u2019s Creek community, south of Cliffside. He built a plant in Henrietta, up the road three or four miles from Cliffside, and he built a plant in Forest City. Then he decided to build one down where the plant is now, so around 1900 they started construction of that, and completed then, it was in operation, I believe, in %u201902, 1902, somewhere around there. But his name was Mr. Raleigh R. Haynes.

CS: Okay.

BB: He later on--the folks that sold his goods that they made at that time, which they started on in a gingham fabric, and then they went to terrycloth products, which includes towels, beach towels, washcloths, and also piece goods of terrycloth that you make bathrobes and all of that out of. They made all of that there. The Cones were the folks that were the selling agents in New York. So they would buy a little stock now and then, and in the fifties, I guess in the %u201954 to %u201956 range, I think is the year--I stand to be corrected--but they bought controlling interest, so then it became Cone Mills Corporation.

CS: Okay.

BB: They had our plant; they had a plant in Avondale. Later on, the one I told you about in Henrietta was sold to Burlington Industries; they owned it. Then we had one plant in Forest City, which is roughly ten miles from Cliffside. So we had three Rutherford County plants, and later, in the last fifteen years, maybe, they built a jacquard plant there in Cliffside that is still in operation. They make the jacquard fabric, the woven patterns, primarily for the automobile industry, upholstery for automobiles.

CS: That%u2019s interesting.

BB: Yeah.

CS: Since there were several mills around here, was there interaction with the different mills, or was it more competitive, or how did it--?

BB: Well, surprisingly, you would have, sometimes, a family, a man and a wife, one would work at one plant and one at the other. Let%u2019s say they were both real good employees. Well, the plant that had either the husband or the wife would try to get the other one to come to work there if they were real good employees, but other than that there was nothing competitive about it. Shelby had several plants that were owned by the Dover family, and then they had others that different companies had, and the rivalry, I guess, came in the form of sports.

CS: Yes, baseball, right?

BB: Everybody had baseball teams. [Laughter]

CS: Did you play?

BB: No. Well, I played early in life. When I finished high school, that was it. I played high school ball, played one year of college basketball here at Gardner-Webb. I had to yield to some more important things at that time, at least. But the question that you asked about the differences in the different plants and villages--I%u2019ve had the comparison with one of my interviews of an employee up in Lawndale. They were like we were. They had a doctor%u2019s office, a dentist%u2019s office. They had a local store, a company store. They had running water; they had bathrooms.

CS: Okay.

BB: So, after one of the interviews of one of the people that had worked up there, I told them, I said, %u201CYou know, y%u2019all are similar to where I grew up at Cliffside.%u201D The only thing we lacked was a hospital. We had a car dealership, we had a movie theater, we had two barber shops, two beauty shops. We had a doctor and a dentist%u2019s office, hardware, and pretty much anything you wanted except a hospital. So this lady said, %u201CYeah, but we had running water.%u201D It was forever before we got bathrooms in most of the houses.

CS: Really?

BB: So I couldn%u2019t say anything. But they were--a lot of them similar. You had, like South Shelby had what they called Shelby Mill, and then there were a couple of them that were south of there, down across the railroad track a ways. Except for playing ball, pitching horseshoes and this kind of thing, and probably playing croquet or different things that you could do at home, most of their time in recreation was spent that way. To go to the movie, which, even though it was nine cents, you know, it was a real treat, and most of the families couldn%u2019t afford to--especially, when they had five and six kids and they couldn%u2019t afford that many tickets, so they made it a point to go periodically. The rest of the time, they played baseball or played horseshoes or something like that. Any kid is going to get entertained some way, if it%u2019s nothing but the pasteboard box a toy came in. They%u2019re going to find a way to entertain themselves.

CS: That%u2019s true. So when you%u2019re talking about the village and the different shops, the company stores, and you had a dentist and a doctor--were all of those shops kind of funded by the company?

BB: Well, the company had--it was kind of a lease deal. Dad and the other barber, Mr. Sparks, they had, in order to use the barber shop, they paid a portion of rent of what they earned. It was like, maybe, twenty percent and eighty percent. But the company also paid for that portion of supplies. Like, each shop had a shoeshine boy, and when they bought the polish, Dad paid eighty percent and the company paid twenty percent. That was the way they got rent. The grocery store, the dry-goods store, all of those were rented out. The main buildings were company buildings and they rented just like you see in a lot of it now, rented to individuals, even the doctor%u2019s offices were rented. And the homes--we were talking earlier about the price of rent--I can remember them talking about each room was a quarter, and we had some places that had--we called them car sheds. Most of them was for one single car. If anybody was lucky to have a car, they had a place to keep it. Well, it cost, like, twenty-five cents a week, so everybody had it made in rent. I can remember, we haven%u2019t talked about this, but I can remember when they paid off in scrips.

CS: Yeah, okay.

BB: You know what I%u2019m talking about.

CS: I do, I think. That%u2019s when they, instead of using money, they would pay with the company%u2026

BB: %u2026Movie ticket%u2026

CS: %u2026papers.

BB: That%u2019s what it looked like to me.

CS: Okay.

BB: And then, folks would have accounts in the store. If they needed some groceries, they would go on and that was charged. When they got their paycheck, it came out. Now, I don%u2019t know how much problem they had with the places in Shelby or Cleveland County as a whole, but there at the plant I worked at--this is before I went to work--I can remember I had some family members that worked down there, and they would go in and maybe work a couple of days, and then they%u2019d get some orders and they%u2019d go back and work maybe another day. It wasn%u2019t going in on Monday and leaving on Saturday. It was a lot of curtailing. It was the word they used, was curtailing. Then, later on, in fact, when I first went to work, there was an area that I worked in, and I was still in high school, and we would go out--it was called the bleachery, where you bleached out all the (28:18) trash or anything that was not desirable in the fabric. You bleached it out. Gray goods became finished goods going through this process. Well, the supervisor would go out to the prior department, which was gray inspection, right off of the loom. We mentioned this morning about the doffing of the rolls and all. Well, they would go out on, like, Wednesday, and check and see how much fabric they had out there to determine whether we were going to work on Thursday or not.

CS: I see.

BB: So it was two, three, sometimes four days if we hit it lucky. But then, by the time I finished college and got into the supervision end, it was pretty much flat six days. Then, and I think some of the plants here did this same thing later on. They went to twelve-hour shifts, which they only had two groups of people working a given day, and they ran the plant seven days. They ran it around the clock.

CS: I see. So before, they only ran the plant six days?

BB: If we were lucky enough to get six days, right.

CS: I see. Okay.

BB: In finishing, we had to a few times run part of the day on Sunday to complete an order, which didn%u2019t set well with anybody. Although it was double-time pay for the hourly folks, they didn%u2019t like it all that much.

CS: Yeah. When did it change to the twelve-hour shifts in the seventies? Do you remember?

BB: It was a good bit after we converted the fabric we were making. I would say it was in, it was probably in %u201985, %u201986, in that area.

CS: Okay.

BB: Maybe just a hair on the nineties%u2019 side. Just to have it in my noggin%u2019, I can%u2019t recall exactly.

CS: What about when they stopped using the scrip? Do you remember approximate when that would have stopped?

BB: The scrip?

CS: Using the scrip in the company store.

BB: Oh, they paid off in cash when I first went to work. Shortly thereafter, they paid every two weeks and paid with a check.

CS: Okay.

BB: I would say the scrip went out in the thirties.

CS: Yeah, okay.

BB: I couldn%u2019t believe that they used to handle all that much cash. You know, at payday, there was a place you went and picked up your money. This day and time, there would be somebody robbing that place.

CS: That%u2019s true. [Laughter] I hear so much about the villages, the mill villages. When did that start to change?

BB: In the sixties.

CS: In the sixties?

BB: Yeah, when Little Rock, all that happened out there, and they started tearing them down and started selling some. There%u2019s several of the homes that came off the village that%u2019s in that (31:31) today.

CS: Okay.

BB: Yeah, it was roughly %u201964, %u201965, in that area.

CS: What do you remember about that time?

BB: I really don%u2019t remember that much because it wasn%u2019t as direct as it was in Omaha. The trickling down that we had encouraged folks, really, to get their own home, or go out in the village and get their own home. I was fortunate enough to go out of the village to get my own house. I was fortunate enough that I was able to get some land near the town. One of my brothers still worked at the plant at that time, I sold him part of it, and he was able to put his house out there, and he could really walk to work. He was in about a mile of the plant, but he could have walked to work if he had had to. It encouraged that kind of thing. A lot of people bought their own homes and bought land outside the town and moved the houses there. They kept the newest ones. On main street, they kept several of those, and there was a street near the cemetery that actually had maybe (32:59) homes. They kept those and they%u2019re still standing. People are living in them. Individuals bought them and fixed them up the way they wanted, and they look real good.

CS: Do you think when that changed and people started living outside of the village, did that change in the closeness of the employees? For example, when we were talking to Jack, he sort of said that everyone was like a family. Do you think that that also changed when people moved?

BB: Oh, definitely. Yeah, it changed. It was kind of like this. If I had a pan of biscuits, you had a pan of biscuits. I mean, it was just, doors were never locked. If they were, it was the screen door, and it had a little latch. If you bumped it just right, it would open up. You know, everybody trusted everybody. You didn%u2019t have crime and all. To answer your question, I guess, when it became a reality that the homes were being moved and torn down, you lost that togetherness. Also, in the town, our school was first grade through the twelfth. Toward the end of my high school days, they decided to consolidate four of the high schools and put them in one. That was good, in a way, even though kids had to, in some cases, travel a good bit more to this centrally located high school. It was probably as equal as you could get. A lot of them are nowhere near equal. One will travel twenty miles and lot of them, five miles. But anyway, that took away from the togetherness too. I mean, even the kids going into high school, they had to learn new friends, and they live, some of them, ten or fifteen miles apart. Back then, everybody didn%u2019t have cars like they do now, so they just saw each other at school, or maybe on the weekend if they went to a movie they would see each other. But yeah, it took away a lot. You see, the village at its peak had, like, five hundred homes.

CS: Wow.

BB: And twenty-five hundred people. That was comparable to your individual villages in Shelby. Probably some of them didn%u2019t have quite that many homes, but it still had similarity.

CS: Did any of your children work in the mills?

BB: Yeah, we had four generations.

CS: Four generations, okay.

BB: My granddad, my mom, me, and my son and all three daughters worked at least in the summer. My son worked, he worked his way up into supervision in the shipping area, and then of course when they began to close down the plant, a lot of them lost their jobs, and they let them go to school. He was one of the ones fortunate enough to go to school and maintain his--he was receiving pay as well at the same time. But the others just were there in the summer, the three daughters, but they all had some real experience. I think I told you my granddad helped build the plant. He was a next-door neighbor to Mr. Haynes. They had farms adjoining each other, so he moved over there with his twelve kids and lived on the village. Then my mom and dad, as I mentioned, both worked in spinning, and then I came along and was in finishing. Then Allen and the girls worked in shipping and the weave room doing primarily summertime jobs.

CS: And did you have brothers? Did they work in the mill?

BB: I had a brother that worked there forty-five years. He%u2019s deceased now. My other two brothers worked there for periods of time, mainly when they were in high school. Neither one of them took the textile career; they did other things. One of them became a college professor and the other one was the recreation director at the state hospital in Morganton. Then he left there into sales. One of my sisters had a career there of roughly forty-five years as well. She was in the finishing department. In fact, when I first took the job, she was under my jurisdiction.

CS: Oh, really?

BB: And my brother that had the forty-five years, his wife also worked in the finishing department.

CS: Uh-oh. How did that work out?

BB: Well, I tell you, it%u2019s hard not to not kind of give in a little bit, but I had to toe the line. My sister gave me no problem, but my sister-in-law%u2026I had to kind of get the facts straight with her a couple of times, but it was fine. I couldn%u2019t have hired them; you can%u2019t hire them to put them in your department, but if you inherit it, that%u2019s a different story.

CS: Right.

BB: But I definitely, I don%u2019t think anybody could accuse me of showing partiality because I didn%u2019t. The only partiality I would show to anybody, if you%u2019ve got four people here and you need one of them to work a little overtime, and only one of them will ever do it for you, the other three, never, if I%u2019m going to show partiality, it would be that one that helps me out working. And I think most anybody would do that. I couldn%u2019t do it, but if I had shown it, that%u2019s who would be working. I%u2019d ask him first, knowing he%u2019s going to take it. [Laughter]

CS: Well, that makes sense. Well, let me just ask you, with these mills being such a crucial part of the economy, and spanning generations of families working in these mills, did you ever foresee, did you ever think that this would happen, or the mills would close down?

BB: Well, I don%u2019t think any of us, for a long period of time, could foresee--all of us thought gosh, we%u2019ve got a job from now on.

CS: Right.

BB: And our kids that want to take the jobs, they%u2019ve got a job.

CS: Right.

BB: And then, it began to show a little, fairly, not all that close, probably in the last five years, you could begin to see some of the handwriting on the wall. But then, something would crop up and make it look--you know, you%u2019d kind of forget that. For example, if we were slack on orders, and we had cut back some--like, if we had been running six days or had cut out Saturday--then that was making it hard on some. But then all at once, you get a big order for somebody that%u2019s going to take six months to complete, you%u2019d forget about the slack time, and not even think about the fact that we%u2019re going to be, one of these days, closing down. It ended up, what really started our slowdown and so many of the others here in Cleveland County was--I know our company went down and bought some stock in a Mexican textile company. And of course, the initial word was that we don%u2019t have to worry about it; the fabric is going to be made down there; it%u2019s going to be shipped to the third-world countries, so it%u2019s not going to take our jobs. It%u2019s not going to take our jobs, and then it will add to the bottom line. Well, all of us had our retirement in stock with the company, and who wouldn%u2019t want some more money on the bottom line?

CS: Yeah, yeah.

BB: So, then in a short period of time, and that could have been two years, you could really see the bottom was falling out, because that fabric that was going to be shipped to the third-world countries was shipped right here in the States and made into fabric. Levi-Strauss was one of our biggest customers, [Phone ringing, recorder is turned off and then back on] and after we could see that the fabric was not going to third-world countries, and Levi and the other customers of ours were gradually getting their work done offshore and then they had a cut in plants. Of course, now, you know, they%u2019re still in business: you have Blue Bell (00:26), you have Levi, and there%u2019s a lot of new ones come on stream. But they%u2019re primarily getting their fabric made in places like Mexico, overseas, and Europe, and getting it finished and made into the various garments offshore as well. And as I mentioned, we have the jacquard plant still in operation in Cliffside. We have the big plant that makes the same thing we did, still in operation in Greensboro.

CS: Oh, you do?

BB: So we are still supplying some goods.

CS: Some of it.

BB: Yeah, so you can still get some American-made if you can find the identification, in blue jeans.

CS: That%u2019s good to know.

BB: And you may be sitting on some fabric in your car that came from Cliffside, North Carolina. [Laughter]

CS: What year did the plant close?

BB: The final production, I believe was in--see, I wasn%u2019t there--I had already retired.

CS: You had retired, okay.

BB: It was after that. I would think it was around 2004.

CS: Okay.

BB: Part of it might have--I know a good bit of it went ahead and shut down as other parts were running. I think 2004 was the actual year it was.

CS: What year did you retire?

BB: My retirement date was 2002.

CS: Okay.

BB: Now, I last worked in %u201999.

CS: Okay.

BB: I think I mentioned maybe that.

CS: Right.

BB: But I was on leave until I became eligible for my full retirement, which was 2002.

CS: Okay. So at that point in %u201999 up to 2002, had they been laying off workers?

BB: Oh, yeah. Yeah, I could see it, and see the handwriting on the wall, but it was too late to do anything.

CS: Yeah, what can you do?

BB: So many of us were depending on the powers to be looking after us, and it got to the point that no longer did that happen. By the way, let me interject this: even though my working years was in Rutherford County in Cliffside, I lived all those years here in Cleveland County, so I have people that came from Cleveland County over that worked with us, and vice-versa, so we had an intertwined kind of thing, but I know a lot of the people that worked here in the county. Even though my career was in Rutherford County, I had a lot of it involving Cleveland County. A lot of the plants, I couldn%u2019t tell you the wherefores and whatnots about them, but some of them I did know along, because I had family that worked in them. I had a brother-in-law that worked at the Esther plant, and you know, two or three more.

CS: What was it like during that time when the mills were starting to close down and so many people were losing their jobs? It seems like such a sad story.

BB: Well, most of them would have like to have gone ahead and applied for a job somewhere else, but the insurance factor came in. A lot of them toughed it out until the last day so they could continue to keep their insurance. It was unreal what you had to pay compared to what you had been paying. In fact, I elected not to even keep mine. I mean, it was like five times, and it got some other--of course, a lot of people couldn%u2019t afford to do that, but if they were drawing, like, if they had retired and were drawing fifteen hundred dollars, it wasn%u2019t uncommon for them to have to pay five or six for that, just for one item--the insurance. It didn%u2019t always include life insurance. It was just for the health and hospital and doctor%u2019s insurance. But it really affected them, and I have to think that was one of the biggest things because that hits your pocketbook, and all the other things tied in hit your pocketbook. One of the best examples I can give you is in %u201976, we were converting to denim from the towel operation. All these people had worked, like the folks that worked in my area, they had been in there their whole career. Well, we were running both fabrics at the same time until one weeded out and the other one took on full-blast. Some of the folks would learn to do the new jobs. Well, the jobs may involve a person that had worked for the last fifteen years on the first shift having to go to the third. A lot of them did that because they knew if they learned that job, that later on they would have a job, and as jobs came open they could go to the first shift. A lot of them elected to stay on their old jobs because during that process the company decided to pay everybody the average wages that they had been used to up until that time, and the better productive people had above standard or normal wages, and they didn%u2019t want to turn that loose.

CS: Right, stuck.

BB: When the shutdown began to come, they toughed it out because of the insurance, and they also toughed it out because they didn%u2019t want to go hunt another job. But then, everybody had to do something there eventually. In 2004, they had to jump on seeing what they could come up with. Now, fortunately, everybody got to go to school for a period of time, and they were paid for that period of time.

CS: Oh, really?

BB: I guess it came from the unemployment kitty, but they had income and they could learn new trades. A lot of them really capitalized on it. I occasionally see some of my older employees, and in talking with them, maybe I haven%u2019t seen them for a good, long while, and in talking with them, I%u2019ll ask them what they%u2019re doing and how satisfied they are. As I mentioned early on about the twelve-hour shifts, a lot of them loved it because they would work, every six weeks, the way the cycle came out, they were off for a week.

CS: That%u2019s nice.

BB: So they didn%u2019t have to take vacation pay if they didn%u2019t want to. And see, that occurred six times a year.

CS: That%u2019s nice, yeah.

BB: But they didn%u2019t want to give that up. But some of them, they got such a--maybe their pay was even greater than what they%u2019d been making, and they thought they were doing pretty good. Most every one of them I%u2019ve talked with, they%u2019ve been satisfied. In a lot of cases that going to school required them to have a complete turnaround in what job they were doing.

CS: Wow, that%u2019s interesting.

BB: So, for the most part, it worked out fairly well.

CS: That%u2019s good.

BB: And then, a lot of them were able to retire, either at sixty-two or sixty-five.

CS: Right.

BB: So it worked out pretty good.

CS: Okay. Do you have anything else you want to say?

BB: Not right now. If you think of something else, give me a call and I%u2019ll try to help you if I can.

CS: Thank you. That was great.

END OF INTERVIEW

Mike Hamrick, October 4th, 2010

Born on December 5, 1937, in Cliffside, Rutherford County, NC, Buzz Biggerstaff was employed by Cone Mills for 45 years, primarily in management. The owner of the mill, Raleigh R. Hayes, built three plants: one in Henrietta, one in Forest City, and the one in Cliffside, which Biggerstaff believes began operating around 1902.

Given his lengthy experience with the mill, Biggerstaff is able to explain a great deal about the operation, the shifts, and the employees, as well as the problems that developed with the closing of the plants and the changes in the mill village, which at its peak had 500 homes.

Biggerstaff retired in 2002, and the mill ceased operation in 2004.

Profile

Date of Birth: 12/05/1937

Location: Boiling Springs, NC