EARL OWENSBY

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 EARL OWENSBY

[Compiled November 10th, 2010]

Interviewee: EARL OWENSBY

Interviewer: Andrew %u201CDrew%u201D Ritchey (DR)

Interview Date: August 12th, 2010

Location: Shelby, North Carolina

Length: Approximately 63 minutes

DR: This is Andrew Ritchey, here with Earl Owensby at his studios in Shelby, North Carolina. It is August 12th, 2010. Just state your name please, and when you were born.

EO: Earl Owensby, 9-30-35 when I was born, yeah.

DR: And where were you born?

EO: I was born at Dysartsville, up in the mountains near Lake James, and grew up in Cliffside.

DR: And what was it like%u2026?

EO: %u2026Probably twelve miles from where Earl Scruggs grew up. Go ahead.

DR: What was it like growing up in Cliffside?

EO: Wonderful.

DR: What did your family do?

EO: My dad worked in the cotton mill.

DR: Did you have brothers and sisters?

EO: Adopted. Only child.

DR: And your mother took care of you?

EO: Oh, yeah. My mother, did you say, %u201CDid she take care of me?%u201D Yeah, from the time I was eleven months old.

DR: Do you know why you were adopted?

EO: I didn%u2019t have no daddy; he was a traveling man. They didn%u2019t need me, so they gave me away.

DR: What was it like growing up in Cliffside? What did you do for fun?

EO: Wonderful, wonderful. It was wonderful, yeah.

DR: What did you do for fun?

EO: What did I do for fun? Well, anything. Now, what did I do for fun? Does the

statute of limitations run on all this stuff?

DR: [Laughter]

EO: I went to work in a theater when I was ten years old, so I worked for fun, and then went to work at a cotton mill when I turned sixteen, and that wasn%u2019t fun.

DR: What did you do at the movie theater?

EO: Oh, I cleaned the place up, ran the projectors, set up the concession stand, popped the corn during all that time. That was it--and watched movies, of course.

DR: Pretty good job for a ten-year-old, then?

EO: It was a job.

DR: You said the cotton mill wasn%u2019t a lot of fun.

EO: Well, it was hard work. Any cotton mill--people who worked in a cotton mill--not easy work, not easy work, and of course, they%u2019re gone, mostly, now, the cotton mills. Lots of people died from brown lung because of the cotton, and I reckon that%u2019s it, Andy. I don%u2019t have no--I don%u2019t know--go for it.

DR: What was the hardest part about the job for you?

EO: In the cotton mill? Just the job. There wasn%u2019t nothing hard about it, necessarily; it was what people did.

DR: So you did that with all your friends then?

EO: Do what?

DR: You worked at the cotton mill with your friends and things?

EO: I worked in the cotton mill with whoever worked in the cotton mill, yeah.

DR: And did you go to school then, too?

EO: Yeah, I went to school. Went to high school, finished high school in Cliffside, and worked the second shift. Went to school during the day and worked the second shift at night.

DR: Did you have any favorite classes?

EO: Do what?

DR: Not a fan of school?

EO: You don%u2019t really want to know about me. You better get on to Earl Scruggs.

DR: No, I%u2019m%u2026

EO: %u2026Because this really ain%u2019t got nothing to with Earl Scruggs playing a damn banjo and being on TV and doing the Beverly Hillbillies thing and having a museum in Shelby, does it?

DR: It does. As I said before, it%u2019s not just about Earl Scruggs. It%u2019s about all of Cleveland County and all the people of Cleveland County.

EO: You%u2019re sure now?

DR: Positive.

EO: Okay.

DR: Are you all right with this?

EO: I%u2019m all right with it. Go for it. I have questions about it, that%u2019s all.

DR: So how long have you lived in Cleveland County?

EO: I got out of the Marine Corps and moved to Cleveland County in 1959. Yeah, %u201959. I spent five years in the Marine Corps.

DR: And what brought you here?

EO: The lady I married was from Shelby, and we just moved here and got a job. That was it.

DR: How did you meet your wife?

EO: Oh, lord, on a date when I was home on a weekend or something--first wife. She%u2019s gone now, but anyway, go ahead.

DR: So when you were in the Marines then?

EO: Yeah, five years in the Marines.

DR: Going back to Cliffside, you said you grew up near where Earl Scruggs grew up?

EO: Yeah, Earl Scruggs is from Flint Hill, and Cliffside is about, from Boiling Springs, maybe five miles--cotton mill town.

DR: Did you know Earl Scruggs?

EO: No, didn%u2019t know him.

DR: Did you know about him?

EO: Yeah, I knew about him. Nice man. Really a wonderful person.

DR: Did you listen to his music or anything like that?

EO: I%u2019m more a fan of--I%u2019m not really a big, big fan of bluegrass, really. %u201CFoggy Mountain Breakdown%u201D was a hell of a thing, you know, with the banjo. I think I lean more to, now, country music. I%u2019m a big fan of Don Gibson. They ought to have a museum for Don Gibson, in all honesty. If you don%u2019t believe that, you go over to the Sunset Cemetery and you see the monument that his wife put on his grave where he%u2019s buried, and you see all the people that recorded what he wrote. %u201CI Can%u2019t Stop Loving You,%u201D the whole deal. He%u2019s something else, something else. I like Don Gibson.

DR: Have you been to the new Don Gibson Theater?

EO: Oh, yeah, went down to see Paula Poundstone when she was there, and she did a movie with me called Hyperspace. Yeah, I%u2019ve been there. It%u2019s a nice theater, really a nice theater. It%u2019s a nice facility. I don%u2019t go to the theaters very much.

DR: So when you came to Shelby--you said your wife%u2019s from Shelby, so you moved to Shelby and got a job.

EO: I went to work for Shelby Supply Company as a truck driver. I moved myself on into sales, which is what I wanted to do anyway, and finally left there and went to work out of Charlotte as sales, and then in 1967, I opened my own company, Carolina Pneumatic and Supply. It was August 1st, %u201967, and then from there, we had started several companies and all, and then I went in the movie business. 1973, I made my first movie, yeah.

DR: What were your first impressions of Shelby when you moved here? Do you remember?

EO: I had none. I had none.

DR: Just a place to live?

EO: Well, you have to have employment and you have to work. I did not want to go back into the cotton mill. You know, I just didn%u2019t want to do that. I don%u2019t know, I guess I picked Shelby because I wanted--I had to live somewhere. Worked out of Charlotte for a while, and then decided to open up my own business and did that? Have you ever gone on the Earl Owensby web page? It tells the story.

DR: How did you decide to--? [Telephone rings]

EO: Excuse me. [Interruption]

DR: So I was asking%u2026

EO: %u2026I don%u2019t mean to have a bad attitude. I just don%u2019t--you know. But if they don%u2019t know who I am by now, they ain%u2019t going to find out, because we%u2019re in 137 countries all over the world. We%u2019ve made forty-two feature films. We bought and sold a nuclear plant, which we made five movies there. We did The Abyss, with Jim Cameron. Listed in Cameron%u2019s book, yeah. Jim Cameron%u2019s a friend of mine. Top filmmaker in the world. How would I be able to prove that? Titanic and Avatar. I don%u2019t have to say nothing else. Spielberg can sit there and twiddle his thumbs %u2018til hell freezes over. Ain%u2019t going to do the six million dollar story. Anyway, I know people.

DR: So you were in sales and then you opened up the movie company. You tried to get in the movie business. What made you decide to make that move?

EO: Would an answer such as because I wanted to? Would that be all right? Because I wanted to. There was a movie--. We did interviews--I%u2019ve been on Sixty Minutes twice, GQ, Penthouse--. You know, I%u2019ve done interviews, Andy. There was a movie came out called Walking Tall, with Joe Don Baker--the Buford Pusser story. I went to see it. I wasn%u2019t in the movie business. It was made in (13:40) Tennessee. That%u2019s where it was made, and I thought (13:45), Tennessee? North Carolina, Piedmont, where we are, seemed like a good idear to go in the movie business, so, when I decided to go into the movie business, what you must do is do a prototype, and so Challenge was the movie that we made and paid for, financed ourself, and it was a hit. Had it not been a hit, I wouldn%u2019t be here. I had a studio and all. It had to be. That was just like fishing, you know. See what happens and it did. It did good, so we went on and we%u2019ve made forty-two features. Some for Twentieth-Century Fox, some for Warner Brothers, Home Box Office, and our own twenty titles that we own, of course, is ours. We bought them and paid for them, and they still sell. That was Elvis, my son, Elvis, there. We just got a distributor on one called Living Legend, which Roy Orbison did the soundtrack for, and that%u2019s what we%u2019re working on now. So, anyway--. That%u2019s the story.

DR: So just wanting to start working in the movie business, is that related at all to%u2026?

EO: %u2026You see, I had been in manufacturing, machine shop manufacturing, screen manufacturing. I had Carolina Pneumatic, which was industrial sales. My background for that was I worked for a major, major company out of Houston, which made the torque equipment for all of the missile things. (15:31), Polaris, you know, (15:35), and I had that background with pneumatic as well as torque controlled equipment. Then I decided to cater to nothing but the man-made fiber industry, along with that special (15:48) and man-made fibers, which would be Celanese, Fiber Industries, Hoechst Fibers, Phillips Fibers, Dupont--I catered to them. I didn%u2019t work no cotton mills, didn%u2019t work whatever, that was it. It went from two hundred dollars in my pocket, and in less than fourteen months, I could write a check for a million dollars and it wouldn%u2019t bounce, so I%u2019m a salesman. There%u2019s a gentleman I have a meeting with that wanted to come in and handle whatever, but, like I told him on the phone yesterday--nothing happens until somebody sells something. Period. Nothing, nothing, so you%u2019ve got to sell something, and that%u2019s what we do. We sell movies, but we%u2019re very careful how we do that. You just don%u2019t want to throw it out there and not get paid, and then they ruin the title, so we take one at a time. We don%u2019t throw somebody out there and you take the whole twenty titles, and--. No, we can%u2019t do that. But anyway, that%u2019s what we do. I don%u2019t know why I got on that subject. It%u2019s got nothing to do with Earl Scruggs. Go ahead.

DR: That%u2019s great. Is going into the movie business at all related to you working in a movie theater when you were ten?

EO: I%u2019ve had that question asked several times. Let me go back. I worked at the theater, doing whatever I had to do at ten years old, you know. You%u2019re a young man, you do whatever growing up and learning to run the projectors and whatever, but I also delivered the Charlotte Observer in the morning and the Shelby Daily Star in the afternoon. So, I delivered papers but I didn%u2019t go in the paper business. Then, when I got to be sixteen, I did a little bootlegging, and I didn%u2019t go into that business either. When I got out of high school, so that ended all that mess, but, yeah. There%u2019s a statute of limitation on the bootlegging stuff, you know.

DR: Can you tell me a little bit about bootlegging?

EO: Yeah, I did bootlegging, sure did. I%u2019m not proud of it--it%u2019s one of them things that you do, you know?

DR: Did many people in the area bootleg?

EO: Not anybody that would have been in my category. They were all professional people. I was real small, doing whatever. You do what you can for a living.

DR: So when you started, you did your first movie. When was the moment that you realized that you could successfully produce movies, direct them, and things like that?

EO: When that one was finished and edited together and we had a New York company, Cinemation Industries, we opened the two Carolinas with it. We opened it ourselves, going into the film distribution, which was not a brilliant idear, but it made money, and so when it made money and was a hit in the two Carolinas, that--people read Variety and whatever--they wanted to buy it. They came with a substantial amount of money up front, and actually at that time, Coca-Cola Bottling Company was using, for a tax shelter, letting them people pick up movies. They picked up Challenge, and United Artists picked up one called The Klansman, which was O.J. Simpson%u2019s first movie, starring Richard Burton and Lee Marvin, I believe it was. Challenge outdid that big-time, and in essence, it just rolled us into the next movie, and so on and so on. Yeah, that%u2019s true, very true. Anyway, that%u2019s what happened.

DR: You mentioned working with James Cameron on The Abyss.

EO: Yeah, I think he%u2019s wonderful.

DR: Do you have any memories of working with him or working on the movie?

EO: He and I were just friends. Actually, James Cameron came here to try to do Terminator because I had a contract with (20:33), John Daley, which was out of England. I think he%u2019s dead now, but anyway, they couldn%u2019t get their money together, so I had a contract with Daley, so he, in essence, changed Terminator to a movie called A Breed Apart with Kathleen Turner and Powers Boothe, and we did that to fulfill that obligation of his and mine both. Then Jim went on later, and they got their money together but they shot terminator in California, so that was--. I had a good relationship with Jim. Jim Cameron is brilliant. I mean, absolutely brilliant, you%u2019d have to say, because Avatar not only set a stage for something, but Avatar, which he had in 3-D and the regular, had to be the most difficult movie to shoot because when you%u2019re doing this computer stuff and you%u2019re doing all this--. Jim Cameron wrote the movie--had no way of doing the movie unless Panasonic and those major people who manufacture hadn%u2019t worked with him, but they did, and then it went on to do three billion dollars. Anyway, that%u2019s just--. Somebody said, %u201CWell, he didn%u2019t make but two movies in ten years.%u201D You let me make two movies in ten years and do that, and you wouldn%u2019t be sitting here interviewing me. You%u2019d have to fly some damn where to interview me, or whatever. But, no, he%u2019s awesome. Golly, he%u2019s awesome. But, he%u2019s down to earth when you start thinking about he did not need the Academy Award, and in essence, he promoted Kathryn Bigelow for her Hurt Locker. When he%u2019d do interviews, he thought she deserved the Academy (Award) and she got it. That was his ex-wife, and she did visit him on the set of The Abyss, but her mindset follows through with him as action-adventure, actually. That%u2019s what she%u2019d done. Gale Anne Hurd was his ex-wife at the time who produced the Abyss. It upset her when Kathryn came to the--. Anyway, and they%u2019re still friends and whatever. That ain%u2019t got nothing to do with Earl Scruggs. I don%u2019t know why I even got on that. But there you go; you got your answer.

DR: Do you remember hanging out with James Cameron when you weren%u2019t working on the movie?

EO: No, we both had a full-time job. I mean, it may sound like this is nothing here, but it%u2019s--and of course, I don%u2019t spend what they spent on The Abyss. I don%u2019t spend the money that--but each one of those movies cost in excess of a million dollars, and that%u2019s in-house making it, but they also brought their money back. Yeah, they did.

DR: Do you have a favorite movie that you%u2019ve worked on over the years?

EO: Yeah, the one that made the most money would be my favorite. I don%u2019t have a love affair once I%u2019ve made them and seen them. I don%u2019t go watch my movies. I don%u2019t like to watch my movies. I%u2019ve got several that deserves a sequel, but I probably won%u2019t do them. But whatever comes across the table, and whatever comes across the desk, I might say that the script%u2019s good and can be put together and has a way of selling it once it%u2019s done. I have people come in here all the time and hand me a script or a story and want to do a movie but don%u2019t have the money. The questions that you ask and the answers you get are pretty well always the same. Somebody%u2019s going to finance it for them. Now, they haven%u2019t yet, but they%u2019re going to, and they don%u2019t have no problem because they%u2019ve been told in Hollywood that, oh, it will do two-hundred-million dollars. It will be a hit. You show me one person that can tell you this movie%u2019s going to do this and it does it, he don%u2019t have to work no more either. But when they say it%u2019s going to do this and they put that multi-millions in it, and it don%u2019t, sometimes they%u2019re unemployed. A lot of the times they%u2019re unemployed. That%u2019s the way the industry is. I%u2019ve never had anyone in Hollywood using that name, the entertainment industry, to help me in any way. In any way. I%u2019ve had stumbling blocks put in front of me, didn%u2019t want me--because I don%u2019t do union--I do Screen Actor%u2019s Guild, obviously, and Director%u2019s Guild. Got no choice with that, but as far as the Teamster%u2019s and (25:59) and all--huh-uh. Noo, that wouldn%u2019t work for us because you do that one time, pretty soon you%u2019re tied to union deals, and that, it don%u2019t work. It doesn%u2019t work for us.

DR: Did you have any problems with the Teamsters or anything like that?

EO: I don%u2019t have a problem with nobody.

DR: You just said you had some stumbling blocks.

EO: Oh, no, when we--like, a movie, when we made Dark Sunday--they rated it X. No profanity, no sex. That%u2019s a (26:31), Wild Bunch, whatever. It shouldn%u2019t have been an X, because it was at the same time Clint Eastwood did Outlaw Josey Wales. Our story was a preacher worked with kids on drugs. The bad guys come in and kill his family, and in Eastwood%u2019s they ride in and kill his family. It%u2019s a revenge thing, and I went through a period it was a battle, because they had the Motion Picture Association of America. So we negotiated, and we went for an appeal, and they changed it to an R before we ever went to appeal. The vice president of NPAA, Dick Heffner, called from LAX airport and said they%u2019d decided to change it to an R. Now, if it%u2019s that damn easy. Anyway, we went to New York for the appeal. That%u2019s a political thing. We ended up with the movie, and you don%u2019t really have to rate them. You don%u2019t really have to do that, so we just put %u201Cnot rated%u201D on it, and away we went. We did good business. But we had those kind of little stumbling blocks, and I realized two names are very important: Smith and Wesson. Smith and Wesson, .44 Magnum, I mean, whatever, if you want to play. You know, I ain%u2019t saying that I%u2019d do that, but that%u2019s the way this whole thing is, just man, golly. But anyway, that%u2019s-- on The Abyss, we were at the nuclear plant we bought. It was fenced in, two thousand acres, and from the top of the hill on the road to down to where we were filming--a mile-and-a-half. We even flew in from New York and they were going to march and protest up on the highway. That was funny. That, to me, had to be funny. I mean, how stupid can you be? Unfortunately, when folks look past the Dixon Line, I think they think we fell off the turnip truck. Probably did, but didn%u2019t land on my damn head, and I said, %u201CYou know,%u201D they come in my conference room, three of them, actually four because there was three lawyers and then the other guy--blue suits, red tie. My lawyer came over--he%u2019s in town, and we said, %u201CI think that%u2019s a good idear. I think y%u2019all ought to protest and walk up and down that road.%u201D It%u2019s way the hell out in the country. %u201CI think you should do that. That would be a good idear.%u201D %u201CWhen can we start?%u201D %u201CWell, don%u2019t you worry about it, we%u2019ll start when we want to unless you give us $100,000. I said, %u201CNo, I can%u2019t give you no money, but go ahead and do that. Now, y%u2019all don%u2019t have no problem with media?%u201D %u201CWhat are you talking about?%u201D I said, %u201CI want the media there. Hell, this is good. This is good.%u201D They looked at me and said, %u201CMr. Owensby, you don%u2019t realize who we are.%u201D I said, %u201CNo, sir, I think what you should realize, I know who the hell you are, and that%u2019s your problem.%u201D Never heard from them again. Never. Why anybody would do it, out in the middle of the woods and protest? What they going to do, carry signs? Them people out there would probably take care of them. I mean, we%u2019re talking about a rough area, but anyway, it doesn%u2019t matter. I don%u2019t even know why I got into that. That was on The Abyss. We did Florida Straights down there with Raul Julia and Fred Ward; we did the Jonestown flood thing for the Department of the Interior deal down there, and they won an Academy Award for it that year, which was a documentary on the Jonestown Flood. I don%u2019t know, but anyway, what else? This ain%u2019t got nothing to do with Earl Scruggs. Why am I telling you all that mess anyway?

DR: The movie business sounds like it%u2019s pretty tough.

EO: More so than anybody would ever realize. It%u2019s not just that you go here and use these eight sound stages and you make a movie, and you edit it and you get the soundtrack done, and when you have to do replacement dialogue, you know? There%u2019s a lot to the manufacturing of a motion picture, and that all falls in. Of course, I get credit for doing this, that, and the other. That%u2019s a bunch of bull. There%u2019s about ninety people. You know, it takes a whole lot of people, and that%u2019s true with Cameron. Cameron don%u2019t miss one man to go out. He can write and he can direct, but they%u2019ve got a crew. The Abyss, at one point, we had four hundred people working on that movie. Four hundred people, so it%u2019s a major, major deal. Anyway, that%u2019s where we are. So that%u2019s what we do. We either do them or we don%u2019t do them. But if it%u2019s not going to sell, you shouldn%u2019t do it. And we%u2019re never going to win an Academy Award, don%u2019t look to win an Academy Award. We%u2019re not in that end of the business.

DR: Have you enjoyed any movie before it%u2019s come out, before you%u2019ve made any money on it? Have you enjoyed the process of creating it or enjoyed any moments?

EO: Andy, it%u2019s fourteen to fifteen hour days, six days a week. We don%u2019t work on Sunday. We have twenty oil-on-canvas paintings of Jesus, birth through ascension, which took thirty-five years for the artist to paint, and we did a movie on those, and I enjoyed doing that, following Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, totally, totally. That%u2019s something I did like to do. It was not as expensive as some of the others, not near as expensive. But we didn%u2019t do it to try to go out and make money on, you know, but we did that. That%u2019s probably have to be my favorite, because we just used the paintings and researched what happened to the disciples and whatever, and it turned out good. That%u2019s one we enjoyed doing.

DR: Did you enjoy it because of the art or did you enjoy it because of your faith?

EO: I enjoyed it because of the subject. The subject was--you don%u2019t find no bigger superstar than Jesus Christ, and he ain%u2019t a member of no union. My opinion, that%u2019s just my humble opinion.

DR: So, over the years that you%u2019ve been running this business, have you ever had to do something that you weren%u2019t expecting when you first got in?

EO: I do a lot of stuff that I%u2019m never--I do my own stunts. I%u2019m in several of the movies. I [pause]--just whatever the script calls for.

DR: What was the hardest stunt you had to do?

EO: Walking on top of a hot-air balloon.

DR: On top?

EO: On top?

DR: How did you do that?

EO: Grabbed on it, and they pumped it up, and I was up on it. We went out to the fairground to do--did it first to make sure I could do it, and went out to the fairground and had a big thing out there all day to raise money for the Oxford Orphanage, which is in Oxford, North Carolina--the Masonic orphans. Somebody thought I was going to be sending my kids to the orphanage when that got over, but I survived it. We went up a mile and went out ten miles and landed. I did it. Drove a car through a burning house, which was in one of our movies, and things like that, but you just think well, the Lord%u2019s going to look after me, maybe. And if he don%u2019t, maybe it%u2019s time to go anyway. It ain%u2019t no big deal. But I don%u2019t care much about any more. I mean, I%u2019ve got awards all over that don%u2019t really--went into the hall of fame, which is fine, but you know, that%u2019s--bottom line is, if you do a movie and it sells, and it does, that%u2019s the bottom line. When that movie is over, I don%u2019t dwell on--I just don%u2019t go back and say, %u201COh look at--that%u2019s a bunch of bull.%u201D But, we try to keep them not being X-rated, which really irritated me with Dark Sunday. I don%u2019t do pornography at all, and sometimes things will come in with a script of somebody else%u2019s movie, and you start reading one thing and then when the shooting starts, it gets into something a little different. We have to be careful with that.

DR: Can you give an example?

EO: No, I would have to name names, but any time one comes in from California, whatever they feel like we%u2019ll do, and I don%u2019t have no problem with nudity. People, I mean, good lord, keep the flies off the watermelon, I reckon. But anyway, there%u2019s certain things that you kind of--I do have to live here. That church on the corner started at our studio. It%u2019s there, doing good. I don%u2019t go there because it got to be %u201CEarl%u2019s church.%u201D No, if it ain%u2019t God%u2019s church, I don%u2019t need to be there. They%u2019re doing good, but it started here for several years. It started out of a Sunday school class that the church we were going to, we had too many members in the Sunday school class, so they wanted to split it up because there was a chance that some of them people in that Sunday school class might get elected deacon. Could I ask a question? What in the hell is a deacon? I don%u2019t know what religion you are, or if you are, but I%u2019m a Baptist, and I guess we have deacons. My wife is an Episcopalian. They have something another, but they go down in front and get the wine and get the bread every Sunday. Baptists are a little bit better than that; they give you curb service. They bring it to you. What religion are you, Andy?

DR: Catholic.

EO: Well, that%u2019s good. There%u2019s nothing wrong with that.

DR: We get bread and wine also.

EO: They do the same thing. See, all that shuffled down from the Catholic, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, you know. Well, I%u2019m just--I think, my opinion, if it%u2019s Christian, I don%u2019t care what denomination it is. We have Jewish folks that come in here, and I%u2019m in the middle of doing some negotiating with Jewish folks now, out of New York. They came down, and of course there%u2019s pictures of Christ here. Most of the time, it will get into the conversation: %u201CWell, you know, Christ was a good teacher,%u201D and he was. %u201CA wonderful prophet.%u201D %u201CYeah, yeah, I agree with that.%u201D And he%u2019s coming, yeah. We use another word: back. You know, he%u2019s coming back. Then I%u2019ll say, %u201CYou know I have the most admiration for the Jewish men. I really think they%u2019re the most optimistic people in the world.%u201D There%u2019s normally two or three sitting there, and they%u2019ll say, %u201CWhat do you mean, Mr. Owensby?%u201D %u201CWell, you know that deal on circumcision? Y%u2019all cut some off befor you know how much you%u2019re going to have,%u201D and they%u2019ll look at each other and they get the joke. But I think, over in Romans, Paul pretty well explained that don%u2019t get you to the gate. I had a lot of dear friends that%u2019s Jewish, and they have their philosophy, and that%u2019s good. I%u2019ve known a lot. I had a condo in Beverly Hills, and the guy that was the manager of (40:04)--I bought Dolly Parton%u2019s condo in Beverly Hills, and he was what they called a converted Jew. It was the first time I had ever seen the Star of David with a cross in it. He wore that. It was a Star of David, but he had a cross in it. He was what they called a converted Jew, and he sat down and explained all that, and I said, %u201CHey, man, whatever you think, I%u2019m on your side. Just don%u2019t let me knock on that gate and not get in.%u201D That%u2019s the way it is, Andy. But we%u2019ll do whatever we can and get it done. Hopefully, people will go see the museum of Earl Scruggs. I hope they do. That would be fine, but that%u2019s still (40:56) had something on Don Gibson. He%u2019s way on up there as far as a songwriter. I had heard people say, %u201COh, he nothing but one of them old mill-village people.%u201D Then I get in trouble by running my mouth. Go ahead.

DR: What about Don Gibson do you love so much?

EO: He was a very talented songwriter. I mean, when you take someone that wrote what he wrote--that%u2019s not easy to sit down and write something that%u2019s going to sell, that other people want to record. He was a good recording artist. I mean, he did real well with the records, and then his wife, I met her. I had never met her before until we went down to the Don Gibson Theater to see Paula Poundstone, and met her at that point. They%u2019d been married a long time. I mean, a long time. But it%u2019s like I had said to her, and it%u2019s true, you take that talent, it doesn%u2019t matter where you come from. Now, I understand he had a little drinking problem. I understand those things. You know, you put them all in a deal, and pretty soon you see them leaving us, and sometimes they left us because they had that problem. Johnny Cash is a good example, and Elvis Presley, (42:33). He never did illegal drugs, but if you could get a doctor to write prescriptions, it don%u2019t matter, it%u2019s still drugs. Then, of course, Ginger Alden, who we did the movie, Living Legend, she--(42:54). She was his girlfriend and the one that found him dead in the bathroom. I don%u2019t think Elvis Presley, ever, in his wildest imagination, could ever realize what he, in essence, became after he died, I don%u2019t think. (43:19). As long as people keep shelling out that money, I reckon.

DR: How did you know Elvis Presley?

EO: Well, I wasn%u2019t a personal friend of Elvis Presley, but as far as the crowd, so you meet people, and, %u201CGood to see you,%u201D and %u201CLove your music,%u201D and all that. [Phone rings] [Interruption]

DR: So, can you tell me a little bit about bringing Roy Orbison in for the Elvis film?

EO: Well, Roy was--and we didn%u2019t do--people thought it was the Elvis Presley story; it was not. We took a rock star, so to speak, and put together a story of that type of story. They guy%u2019s name was Eli Canfield--nominated Best Movie of the Year, Academy of Country Music--didn%u2019t win. Willie and Robert Redford won for Electric Horseman, but it was California. The thing that I thought, I%u2019m--any movie we make, I go over it and over it and over it in my mind. Sometimes I don%u2019t win. Sometimes I don%u2019t win because if you have a director and you have a writer, you have hired them and paid them for their vision. I%u2019m only setting back in the sales deal, but I knew that Roy was Elvis Presley%u2019s singer, and I did a movie that one of my people in it was Ed Parker. Ed Parker and I became real close friends. He was Elvis%u2019 bodyguard and Kenpo karate instructor and all that, and a star in his own right. He and I just became buddies. He was going to be in that movie, and then he has a tournament, or had a tournament out in California with karate, whatever. He was the one that developed Kenpo karate; he was the world%u2019s leader in that deal. We talked about it and he suggested Ginger. He said, %u201CShe%u2019s really a gorgeous lady,%u201D and she hadn%u2019t grabbed a hold of the fact that she was there when Elvis--she didn%u2019t play on that at all. Didn%u2019t need to after that sort of jewelry that he gave her--a little mechanic%u2019s metal thing that was full of diamonds and everything. He didn%u2019t pay for them, but the people out in Las Vegas threw it on the bed--Mafia, of course--and he didn%u2019t want it, gave it to her. But anyway, long story short, I started putting it together and wanted Roy to do the singing %u2018cause there ain%u2019t no way I%u2019ve recorded before and had the hit records, but I ain%u2019t doing what nobody--that%u2019s what Roy Orbison does. So I flew over and met with him and his wife, Barbara, at his house, and just told him the whole deal, and we come to an agreement, basically. He lived right beside Johnny Cash. That%u2019s where he lived. So we had coffee, and Barbara left and come back with more coffee. I said, %u201CNo, I%u2019m fine on coffee.%u201D She said, %u201CNo, Mr. Owensby, the man in black had to get up and give me that coffee. It would be nice if you%u2019d thank Johnny for it and drink it.%u201D And I knew Johnny. I knew Johnny; I had met him a number of times. But anyway, we come to the agreement that he would do the soundtrack. Now you have me--going to star in this movie with Ginger Alden and all these people, and we can%u2019t shoot the concerts. We can%u2019t shoot the things that has the singing going on %u2018cause Roy ain%u2019t done it yet, so he brought his band from Oklahoma and they started working on it. He come up with the ten songs that we needed, and went over to Arthur Smith Studios in Charlotte and recorded the soundtrack. The movie was awesome. It just turned out to be dynamite and got nominated for all this stuff. Not because of Roy, but it was just unusual; nobody had done that. We sold it when we had the (49:07) thirty-five millimeter. Had a call from a guy with Pacific International, which was a distributing company, and wanted to buy it. We flew out there, and after two days of him bringing nine people to the table, and myself and my president, it went on to that, and I finally got up and said, %u201CThe heck with it.%u201D I walked out on the streets; he followed me, and he got to running his mouth. (49:49) was his name. I said, %u201CMr. (49:52), the only way, if you wire-transfer the money to my bank account and I hand it to you (49:58) number by tomorrow morning at ten o%u2019clock, that%u2019d be fine. Now, if you get in my face one more time, I intend to clean up Sunset Strip with your ass,%u201D and I laid down my attach? case, which was true. I%u2019ve been known to do that, and you shouldn%u2019t, and I know that. I don%u2019t do that no more. I got too old; somebody will whip me. He looked at me, and he said, %u201CI guess you just don%u2019t push ol%u2019 Southern boys around, do you?%u201D I said, %u201CWell, I don%u2019t know nothing about Southern boys or who you push, but man, I%u2019ve been hearing you for two nights here, starting at four o%u2019clock and going to eleven, and all I have is a movie, and it%u2019s called Living Legend, and this is who%u2019s in it and this is what it is.%u201D He wire transferred me double what I had in it, and I had a contract, which he did not live up to. Didn%u2019t live up to it. Six months went by, so I got the movie back. I didn%u2019t go out to that deal. He was in Medford, Oregon, and my president and my lawyer out of Charlotte flew out, and he signed the paper and gave it back to me. But, I didn%u2019t know at that time, it had been alleged that he took his daughters camping, and that wasn%u2019t real good what the word went out that he was the type of person, so he just kind of bailed out. But we got the movie back and it sells all over the world. As a matter of fact, just did a DVD deal with it, my son Elvis did. They%u2019re doing a new campaign and it will be in Best Buy and it will be in Wal-Mart and it will be everywhere. I%u2019ll be saying thank you, thank you very much, I appreciate that.

DR: So you named your son after Elvis Presley?

EO: Elvis Presley, yeah.

DR: Do you have any other kids?

EO: Oh, yeah, Rhett works for me, my son Rhett. And my oldest son, Dennis, is in the construction business over in Gramling, South Carolina. He didn%u2019t like the movie business. What he didn%u2019t like was six days a week, fourteen-hour days, and the pressure, but there%u2019s a lot of pressure. You just have to stop and think that you%u2019re going into a business that you%u2019re competing--you%u2019re not competing with people who have a service station on the corner--you sell gas; he sells gas. You%u2019re not competing with somebody who has a clothes store, and you%u2019re at the mall with the rest of them. You%u2019re competing with people with billion-dollar companies. I can tell you (52:45). That%u2019s just the way it is, and when you shuffle down with unions, Screen Actors Guild--. I%u2019m a member of the Screen Actors Guild, which is fine. If you do a movie that has Screen Actors%u2019 people in it, you%u2019re going to sign with them and pay them; that%u2019s what the deal is. Directors Guild, which we don%u2019t normally use unless it%u2019s somebody like--they send you Cameron, or the Hemdale guy, (53:17), they pay. What we get is, we have a car wash; we%u2019re ain%u2019t going to change the oil; we%u2019re going to wash your car. That%u2019s sort of what we furnish is what we furnish and it%u2019s in the contract, and what we get paid for it. But as far as signing a union contract with this studio, or we didn%u2019t with the nuclear plant either because we wouldn%u2019t be able to survive that. You can%u2019t fight Universal and the unions and Fox, and you can%u2019t do that. I mean, it would be nice to say, %u201CWell, I%u2019ll take %u2018em on.%u201D They%u2019re going to whip your butt. Now, Fox left here owing me $300,000. Twentieth Century Fox, on The Abyss. And their answer was, %u201CWell, we probably owe you, but sue us.%u201D That was the answer from Twentieth Century Fox. So, I believe in doing what folks ask me to do: I sued them. They made a mistake. They thought--now, they had eighty lawyers. They thought we%u2019d go to California and fight it, so we get out there and they put it off. So, back and forth, so then we decided (54:26) in the whole deal, since they shot the movie in Gaffney, South Carolina and they paid their bills in Gaffney, South Carolina, Fox did, and everything was fine, then we%u2019d try it in Gaffney. Clifford (54:44) was the guy%u2019s name, head lawyer. He called me and said, %u201CMr. Owensby, could I come see you?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah, Clifford, come on out. You going to bring me a check?%u201D He said, %u201CCertified.%u201D I said, %u201CWell, why?%u201D He said, %u201CYou got the damn trial put in Gaffney, South Carolina, to the good ol%u2019 boy network. And next time you fall off that damn turnip truck, just land on your head if you don%u2019t mind.%u201D We made a joke and they brought me the money, but it took about four months between--and I%u2019m in Variety every day and we were battling Fox--that wasn%u2019t doing me no good. You know, I%u2019m %u201Cbattling them, battling them,%u201D but they did pay me. They paid me and I went on to the next deal. Lordy, mercy. But North Carolina has a film commission, Andy, they have one. I brought Dino De Laurentis here to make a movie called Firestarter; we couldn%u2019t get together, so he went on to Wilmington. They promote, you know, anything they could do. Never, not one time, has the State of North Carolina Film Commission, ever sent anyone to me to make a movie. Never. Not one. Not ever. Nobody has ever. Maybe I just don%u2019t have the personality and politic with the film commission, because the film commission don%u2019t have a clue of how to make a movie. They just don%u2019t. When someone comes in looking for locations, they%u2019ve carried them everywhere. They don%u2019t bring them here, but that don%u2019t matter. I don%u2019t--that%u2019s it. I tell everybody that EO don%u2019t mean equal opportunity. I don%u2019t think it does.

DR: Now you talked a little bit about working with Roy Orbison and knowing Johnny Cash a little bit. Do you play any instruments or sing at all or anything like that?

EO: I%u2019ve had a couple of CDs. I don%u2019t push that. One of them got to be a hit called Cotton Mill, which did whatever. That%u2019s not my thing.

DR: If you don%u2019t mind, you were a little anxious earlier to talk about your relationship with Horace Scruggs a little bit?

EO: Oh, Horace? I just knew him. He played in a band with one of my former doctors, Dr. Jones. He worked at Gardner-Webb College. That%u2019s all I know. I think he passed away, but I%u2019m not sure.

DR: How did you know him? How did you meet him?

EO: He played in a band with Bobby Jones. I didn%u2019t know him that personal.

DR: Okay.

EO: I don%u2019t think he worked in a cotton mill. I think he worked at Gardner-Webb University.

DR: Did you pick up any stories about him?

EO: Huh-uh.

DR: You%u2019re a businessman--what%u2019s kept you in Cleveland County?

EO: A ten-million-dollar damn studio! [Laughter] I have a home in Rutherford County. I had a farm out near Boiling Springs, between Boiling Springs and Cliffside. I sold it and then when I did, I bought a house back in Rutherford County. I have a house here--seventy-two-hundred square feet--didn%u2019t want to live there. I lived there for a long time. So, you know, that%u2019s it.

DR: Okay. Well, you could conceivably sell the studio and open somewhere else, though, right?

EO: I ain%u2019t going to open nothing nowhere.

DR: You%u2019re happy here, then?

EO: Whatever happens.

DR: How has being located in Cleveland County affected your business?

EO: Well, it goes back to a story, and I don%u2019t know the whole thing, but a guy wanted diamonds and he searched all over the world for a diamond, and finally sold his place that he lived at, and the guy that bought it found the largest diamond ever. You know, them kind of things, but, no, I%u2019m not out a looking for anything, period. I bought a nuclear plant and turned it into a studio and sold it. I had partners in it and they bought me out, and then I think Duke Power%u2019s got it back now, going to build a nuclear plant, but I don%u2019t know. But you%u2019re talking about thirty years and forty billion dollars, so it ain%u2019t going to bother me. But that%u2019s it, my friend. I appreciate you interviewing me.

DR: Thanks. Do you mind if I ask one more question?

EO: Ask one more question.

DR: All right. Over your time in the movie business in Shelby and Cleveland County, how have you seen either the movie business or the county changing over the years that you%u2019ve been here?

EO: The movie business changes all the time. It will change next year for some reason. Now we%u2019re back into 3-D, and I%u2019ve made more 3-D movies than the damn people out there. I%u2019ve made six 3-D movies. I made the first 3-D movies in twenty-five years, but that%u2019s okay. It was called Rottweiler. But that changes--now we%u2019re going to have 3-D TV, and all of a sudden they%u2019ve realized--they come out with 3-D movies. Invictus was not a 3-D movie, yet it was number one for two weeks in a row. It was not a 3-D movie. The second one in line was (1:01:02) was not a 3-D movie, with (1:01:04). Then last week, we had--the number one was (1:01:09), with Will Ferrell, and it wasn%u2019t a 3-D movie, so they%u2019re now tending to say, %u201CWell,%u201D and personally, if I%u2019m watching television, I don%u2019t resent seeing an old classic in black-and-white. That don%u2019t bother me. I think it%u2019s absolute wonderful because when you forget what the story is, and worry about the technical, you get lost anyway, but that%u2019s just the way it is. And it changes, and it will change again. They come out with 3-D TV--still wear glasses. I don%u2019t think--but that%u2019s just me. It might be the biggest thing that ever happened, and then again, it might not.

DR: In the county? What about the county then?

EO: About the what?

DR: Cleveland County, how has it changed?

EO: Oh, I don%u2019t keep up with Cleveland County. When I was in the industrial business, Fiber Industries was here. When you start talking about what I catered to, it%u2019s not here. Fiber Industries is gone. The cotton mills are not here. I never did work the cotton mills, but Cleveland County is changing. I don%u2019t get involved in the county end of it. I certainly don%u2019t get involved in county politics or anything like that. It%u2019s obviously not like it once was because of the things that%u2019s gone. I don%u2019t know whether they%u2019re out working to bring more industry in or not. I have no idea, but we%u2019re here, and that%u2019s it. We are in the hall of fame deal and that%u2019s fine. I%u2019ve got another award coming up in Indiana in September. I just got an email congratulation. I was the top filmmaker, blah-blah-blah, which is not worth anything. It won%u2019t get me a hamburger at Hardee%u2019s. So I don%u2019t know, Andy, I reckon we just keep doing what we do, and that%u2019s it. So I%u2019ll walk you out and get my other guy in here and I%u2019ll start negotiating.

DR: Thank you.

END OF INTERVIEW

Mike Hamrick, November 10th, 2010

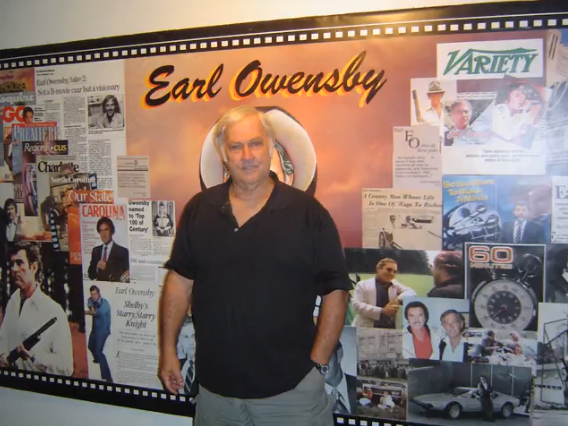

Earl Owensby was born September 30, 1935, in Dysartsville, N.C. and grew up in Cliffside, N.C., the only child of adoptive parents. When he was ten years old, Owensby worked in a movie theater operating the projector and running the concession stand. While in high school, he worked second shift at a cotton mill and he said he was involved in smalltime bootlegging when he was 16 years old.

Owensby moved to Shelby with his first wife in 1959 after five years in the Marine Corps. He started at Shelby Supply Company as a truck driver and then moved to sales. After several more sales jobs, he started his own company, Carolina Pneumatic, in 1967, followed by several other businesses.

Owensby explained that when he saw “Walking Tall, the Buford Pusser Story” with Joe Don Baker and discovered that it had been filmed in Tennessee, he decided he would make movies in North Carolina. He made his first movie, “Challenge,” in 1973. Owensby established his own movie studio and has made 42 feature films, including “The Abyss,” with director James Cameron, and “Living Legend” with a soundtrack by Roy Orbison.

He said he has performed stunts for his movies, including walking on top of a hot air balloon and driving a car through a burning building. He bought a nuclear power plant, turned it into a studio, and sold it. Owensby said his movies are distributed in 137 countries.

Profile

Date of Birth: 09/30/1935

Location: Shelby, NC