THE CABANISS FAMILY

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 CABANISS FAMILY

[Compiled September 17, 2011]

Interviewee: CABANISS FAMILY

Interviewer: Dwana Waugh, Joy Scott

Interview Date: July 15, 2008

Location: Helen Barrow%u2019s house on Suttle Street, Shelby

Length: Approximately two hours, forty minutes

TANZY WALLACE: I wanted Stuart just to hear this, cause it%u2019s good %u2013 I want my kids to hear it.

DWANA WAUGH: Yeah. We can just start however you wanna start, or I just ask if you could talk a little bit about what it was like growing up in Shelby %u2013 what you remember. You could start on a snowy night, or rainy night [laughter].

TW: Are we going to start in order?

PETER CABANISS: We may get around to that ( ). [laughter]

TW: Momma %u2013 you%u2019re the first born.

HELEN BARROW: Well, we always had inside toilets %u2013 some people still had outside toilets, but we always had toilets in the house. We went to a all-black school %u2013 Cleveland School %u2013 I graduated in 1953, so it was from 1941 to 1953.

TW: It went first through twelfth?

HB: Um-hmm. All one school %u2013 first through twelfth.

TW: It was all the grades. Right here at Cleveland School, right over here on %u2013

HB: Hudson Street.

TW: Hudson Street?

HB: Over there at Hudson and Webber Street.

JOY SCOTT: What was the atmosphere like at Cleveland School?

HB: It was good. I enjoyed it very much.

DWANNA WAUGH: Do you remember any teachers, or principals?

HB: Yeah, the principal %u2013 greatest principal. The first principal was Bonnie Roberts, and when I graduated, the principal was James Hoskins. And he was the last principal of the all-black school to when the schools merged, he was still the principal of the sixth grade school there. One of my teachers was Miss Ezra Bridges %u2013 you know Miss Ezra Bridges? She was my third grade teacher. And Miss Louise Howell was my second grade teacher. Mrs. Cara Mack, first grade teacher. Mr. Devon was chemistry and science and math teacher, and Mrs. Martha Simpson was the English teacher. Mrs. Dorothy Womble was the home economics teacher %u2013 they called it home economics then. Mrs. Dorothy Williams taught history. Miss Tula Byers %u2013 she taught English also. [pause]

JS: What was Miss Bridges like as a teacher?

HB: Oh, she was beautiful. She was a very, very good teacher %u2013 she taught me third grade. She still remembers me [laughs]. She%u2019s over at the nursing home now, at Cleveland Pines. And she could tell you more about the ( ), the first school, the county schools, than I could, cause I wasn%u2019t born yet when that school was being run. So she could tell you a lot about everything. She%u2019s a very good historian.

DW: Did you grow up %u2013 we just learned about the communities %u2013 the Flat Rock community?

HB: Yeah, Flat Rock community. We lived on Pinkney St., over there where the post office %u2013 near to where the post office is now. That%u2019s when we lived on Pinkney Street, and Pete lived Pinkney Street too, until the redevelopment of the community, when my mother and father moved out to the outskirts of town, but we lived over there till the sixties, in the sixties, wasn%u2019t it? And maybe the seventies, cause we moved back %u2013 we moved back to Shelby %u2013

PC: I was in college when %u2013 cause I came home to help Frank and Raymond move up to Timberlake Drive.

HB: But that was in the seventies.

PC: It was in -- probably %u201978.

HB: Yeah, it was in the seventies. When they read about when then Flat Rock became another community.

PC: Urban renewal came through, and decimated %u2013

TW: %u201976.

HB: Was it %u201976?

TW: Um hmm. It was in the seven %u2013 well 197 --

PC: %u201978 then.

TW: Well, we were in high school when you all moved up to Timberlake.

PC: Huh-uh. I came home from college.

HB: Aunt Mildred %u2013 no, you were first year college.

PC: First year of college.

HB: Cause Aunt Mildred was here, and she was living with Mother and Daddy when we had to move her up there too.

TW: I remember being in high school.

HB: Yeah, when you were in high school they lived on the %u2013 but we lived here, we moved here in %u201974.

TW: Right.

JS: What was it like to go through that urban renewal process?

HB: Oh, I caught the tail end of it -- they were just going through, as people found places to move, the city would help them to move. Cause I think Daddy was about the last one to move, wasn%u2019t he?

PC: Yes, he was. It was a mixed blessing; there was mixed emotions. Most everybody that went through urban renewal was able to get a better house. I doubt if people could have sold their houses, and even the people who were renting, there was assistance for them to move into better houses. I would say %u2013 maybe forty percent, maybe fifty percent %u2013 actually moved from an all black community to an integrated community, including all my family. I think from the standpoint of having a better material quality of life, that was accomplished. Although from a community standpoint, there was definitely heart strings that was torn. Cause that was a community that had been together %u2013 oh for probably close to eighty, seventy years %u2013 since the early 1900%u2019s, with the church being founded by Mr. Yarrow Roberts %u2013 that%u2019s somebody you definitely want to talk to %u2013 her father or grandfather?

HB: Her father.

PC: By her father, Roberts Tabernacle Church, so %u2013 you know, there was excitement, a little %u2013 I don%u2019t know if trepidation would be the right word, but anticipation in %u201Cwhat is this new community going to be like?%u201D You know, I think once people settled, they %u2013 even though their material surroundings had improved %u2013 I think there was a great sense of loss. To the point that the Roberts Tabernacle began to have semi-annual Flat Rock reunions. And they%u2019ve grown in popularity over the past %u2013 how many years?

TW: A while.

HB: Is this the seventh one? I guess we have fourteen years %u2013 cause they do it every other year %u2013 so the last one was the seventh one.

PC: So you do want to talk to some people, like Miss Black %u2013 what%u2019s Miss Black%u2019s first name?

HB: Frances, Frances Black.

PC: Mrs. Frances Black, and Miss Lidessa Brooks, and %u2013

HB: Mr. Webber.

PC: Mr. Webber.

HB: And ( ) Burn.

PC: Mr. Burn, and Mrs. Hester Ann McKissey. You know, when it comes down %u2013 these are some of the long-standing members who are still living %u2013 of Roberts Tabernacle.

HW: And Roberts Tabernacle is still in the same neighborhood %u2013 it%u2019s right here up on Marion Street, so that was the church that was on Pinkney Street. Then %u2013 we said we wanted to still stay in the neighborhood, so the city helped us to find some land in the city that we could still stay in this neighborhood.

PC: Now, you know %u2013 to think about it -- I think that%u2019s probably the only black community that the community as a whole was displaced. And %u201Cdisplaced%u201D is kind of a pejorative term; I don%u2019t know if you would actually say %u201Cdisplaced,%u201D but relocated.

HB: Relocated, yes.

DW: Just the Flat Rock community?

PC: That%u2019s as far as I know %u2013 the Knot, and there%u2019s some places that house by house, but en masse %u2013 that was something that happened over a very short period of time %u2013 over a two year period of time %u2013 the community was %u201Cevacuated%u201D %u2013 how%u2019s that for a pejorative term? [laughter] We were refugees! Tell them that ( ) -- that renewal made us refugees in our own land! [laughter]

TW: Was Creekside part of %u2013

PC: Creekside was part of it.

TW: Flat Rock %u2013

PC: Flat Rock, Creekside, Blackbottom, and Jail Alley.

DW: [laughter] Is that really the name %u2013 Jail Alley?

TW: That%u2019s what they called it.

DW: Okay.

PC: Yes.

HB: That%u2019s where they put the jail %u2013 they moved the -- where the [claps] courthouse is now %u2013 that was part of Flat Rock. That was Arey Street Jail House.

TW: And there was a brick %u2013 I remember that %u2013 I used to come to Shelby in the summers %u2013 my dad was in the Air Force. And I used to come to Shelby every summer, and I loved Shelby because I remember that community. And every summer I would come for about two months, and my grandfather %u2013 I remember the store. I remember he would always have hot dogs, and I remember Chek sodas %u2013 Winn Dixie Chek sodas. And the whole neighborhood would come up there, and he would sell hot dogs for what %u2013 a quarter, ten cent, a quarter? And the kids would come up there %u2013 just the whole community, and everybody knew everybody. But I know I couldn%u2019t go no further than the church %u2013 I couldn%u2019t go %u2013 I knew my boundaries. But it was just a very loving community. People were very, very friendly. And it was like when someone came from out of town, from up north or whatever, it was like a homecoming. You know, just excited to see people come into that neighborhood. It was a very embracing neighborhood. [phone rings] And my grandfather also knew that black children did not have the opportunity to have extracurricular types of activities, especially during the summer. And I used to help him every summer %u2013 Pete and I used to help him every summer %u2013 he would have about seven to nine busloads of black kids and their families from all over the county. And I think it may have been %u2013 the most I can remember is ten dollars a ticket %u2013 and he would take them up to the Asheville Zoo, up to Lake Lure, and just get a full day outing. And he did that every year for a long time. See back then, kids didn%u2019t have Nintendo, all that, and those extra activies %u2013 and everybody looked forward to that. And I remember chicken, fried chicken %u2013 everybody had that %u2013 they had boxes of stuff! And everybody would share their fried chicken %u2013 it was just wonderful.

PC: It was a grand time. If you talk to people around, they will tell you that %u2013 that they miss those days.

HB: Yeah, they do talk a lot about that.

PC: And one of the things that I seen was the transformation, because people didn%u2019t have cars, and they couldn%u2019t travel. Then there was a brief period of prosperity, when the mills came to town and people were driving cars, people could go places; but then there was the onslaught of drugs in our community. And now you have a whole group of kids that don%u2019t get to go anywhere. Just like it was back then. You go to this neighborhood right down here, and some of these housing projects, and you will find kids that %u2013 you will find fifteen or sixteen and eighteen year-olds that%u2019s never left Cleveland County.

JS: What do you think it was about your father that %u2013 you know, it takes a special person to say %u201CI%u2019m going to organize this, and I%u2019m going to do this for kids that aren%u2019t mine; I%u2019m gonna do this for the neighborhood.%u201D What was it about him %u2013 more than just saying %u201CI know people don%u2019t have opportunities for recreation%u201D %u2013 but what was it that drove him, that motivated him to do this for the community?

HB: I guess he was just a caring person. He was very outgoing cause he had the first %u2013 the grocery store was the neighborhood grocery store. We lived next door %u2013 the house was here, and the grocery store was next door %u2013 so he was just a outgoing person, because they looked forward to %u2013 they knew that he would do something for them all. He had a caring heart for other people.

PC: I always said he was one of the early visionaries, and he could see that -- cause he gave us plenty of experiences. We always had magazines, and he always took us places, and he had enough vision to know that if he could create a sense of hope, or a sense of vision %u2013 if he could show you something of it in your surroundings, that perhaps you would strive to leave your surroundings. And you could help me with the terminology on that.

TW: A choice %u2013 that there are other options.

PC: That there was other options. And like Helen said, he was a very kind man, a very, very, very, very loving man; and he wanted to expose the children of Cleveland County to a world outside of their environment.

TW: And if he couldn%u2019t take them there, he would bring it here.

PC: Oh, that%u2019s so good!

TW: If he couldn%u2019t %u2013- like the singers and stuff, he would have %u2013 he was the first person %u2013 he had The Staple Singers out at Holly Oak Park. I mean, people came from %u2013 I know as far as Hickory %u2013 they came from all over. There was no entertainment %u2013 it was live entertainment at Holly Oak Park. [someone clears throat] I remember --

PC: And the Armory as well.

TW: And the Armory. He had Bo Diddley %u2013

HB: The Staple Singers.

TW: The Staple Singers, Aretha Franklin, Joe Tex.

PC: The Tams.

TW: The Tams.

HB: Who was it %u2013

TW: Kool and the Gang. [Laughter and everybody talking at once] I was fourteen years old --

PC: And the Bar-Kays.

TW: He had the Bar-Kays. I remember I was fourteen years old, and he wasn%u2019t going to let them stand him up. We drove to Winston-Salem, and he got Kool and the Gang, and they followed us to Shelby, and they stayed %u2013 I don%u2019t know if they stayed at the house %u2013 but I remember I met %u2013 Percy met Kool %u2013

DW: Oh wow. [laughs]

HB: Yeah %u2013 he swears he went to Winston-Salem %u2013

TW: He went to Winston-Salem cause that was their %u201Cgig.%u201D

PC: They were doing an outdoor concert in Winston-Salem, and the following night they were going to be in Shelby. He wanted to make sure them rascals didn%u2019t get lost between --[laughter and everybody talking at once] It was like %u201CI ain%u2019t gonna put my name on no program%u201D %u2013 everybody running around saying %u201CI knew they%u2019re wasn%u2019t gonna no Kool and the Gang!%u201D We wanted to get them here on their bus, so they could drive the bus around. He was a big promoter %u2013 he knew marketing like nobody else %u2013 before or since %u2013 him and Donald Trump would have been good buddies. [laughter] He brought them here on their bus, and then he made them drive that bus around town, so people would know %u201Cyeah, they here, they here!%u201D [everybody talking at once]

JS: So how did he come to know all of these people %u2013 he was just %u2013

TW: He was a %u2013 what do you call it?

PC: He was a promoter, and his father used to promote singings %u2013 Walt Cabaniss.

HB: He had a quartet group.

PC: Okay, yeah -- he had a quartet group.

HB: He had a quartet group. But Daddy didn%u2019t sing, he was the one that promoted ( ), but Papa had a group %u2013 he just carried his own group around.

TW: And it was always a family thing %u2013 Mama always handled the money when they came in. And I remember every summer coming down %u2013 he would have it at Holly Oak Park %u2013 and the two first black police officers -- they%u2019re now deceased %u2013 Mr. Bass and Mr. Brooks %u2013 they were always -- he would always security there at Holly Oak Park. But yes, I remember %u2013 what%u2019s his name? Stowe %u2013

HB: Wray.

TW: Wray. I was uptown %u2013 they owned Wray%u2019s %u2013 it was a family-owned business, it%u2019s not there any more %u2013 it%u2019s a clothing business that was uptown %u2013 I remember talking to him one time, and he said %u201Cyeah, I know Mr. Wray. I wanted to go see Bo Diddley up there at the Armory, and Mr. Wray told me to go upstairs.%u201D He was a white man. He said %u201Cyou gonna have to go upstairs.%u201D Because, you know, it was during the fifties or early sixties, and he said %u201Cyou can%u2019t come down here with us, you gonna have to go upstairs.%u201D

DW: How interesting.

TW: He let him come in, but he had %u2013 I think he showed people that they can defy how people define you. He was a risk-taker, and apparently there was something in him that said %u201CI don%u2019t have to stoop to what people%u2019s opinions are about me,%u201D and he just had the tenacity, he was a %u2013 I wanna say he was a %u2013 raw.

HB: Very daring.

TW: Very daring, just raw. You know, he was right there, but that compassion was there too. It was like -- he just wasn%u2019t gonna bow down.

PC: I think %u201Cbold%u201D would be a good term.

TW: Bold, yeah. Very bold.

DW: Was that his primary job, that he was just a promoter, and the neighborhood store owner?

PC: He used to hold between seventy and eighty primary jobs. [Laughter]

HB: This was extra. He had to have a job to take care of his family, so this was the extra. [everybody talking at once]

TW: He was an insurance man, he was in insurance.

PC: Insurance was his primary %u2013

TW: -- his primary, his base. Then he sold eggs %u2013

PC: He was a produce %u2013

TW: And he sold apples, canteloupes %u2013

HB: Peaches.

PC: Christmas trees.

DW: He was a man of all seasons! [laughter]

HB: He said he had to take care of his family, so he had to %u2013 you know %u2013

PC: He had a good hustle %u2013 he had hustle.

TW: You know the last thing I remember Daddy Ray %u2013 he was out there where Sky City used to be %u2013 where %u2013 out there on 74 %u2013 it%u2019s where %u2013

HB: What%u2019s that place used to be %u2013

TW: There%u2019s a Sub Station, but there%u2019s a little tract mall behind it %u2013 sort of a ghost town now.

HB: Where Kimbrell%u2019s furniture store %u2013

[everyone talking at once]

TW: Yeah, Maxway%u2019s used to be %u2013 the last memory I have of my grandfather selling something %u2013 he had to be up in his seventies %u2013 he was sitting up there in that parking lot, and he had cantaloupes, and he had a little bit of stuff on the back of his station wagon. I said %u201Cthere%u2019s Daddy Ray till the end.%u201D He was up in his seventies.

DW: Wow.

TW: And he was selling some stuff. He always %u2013 he was always %u2013 what you call it %u2013 a gatherer and storer. [laughter] Definitely an entrepreneur.

HB: He%u2019d go to the mountains and get apples %u2013 he%u2019d sell apples in the fall.

TW: Uh-huh, uh-huh.

DW: What about your mom, your grandma %u2013 what did she do?

TW: She was a little business woman %u2013 a working woman.

PC: She was the first black dietician for the school systems, I guess. She actually went to A&T to get a certificate in dietary %u2013 what do you call that, Helen?

HB: Yeah, she was dietary %u2013

PC: And you have that in there, don%u2019t you? You have a picture - it%u2019s in the scrapbook, isn%u2019t it? Her graduating class. And so she planned the meals for the Negro schools in Cleveland County, for all the schools. Because she cooked in all the schools too. And she always knew the kids who %u2013 that might be their only meal %u2013 and she always gave them something extra. And then the little boy going through the lunch line %u2013 I always got me a little something extra too. [laughter] I always got me two ( ) cookies!

DW: So you said she also cooked in the schools.

PC: Oh yes. Her and Miss Lidessa -- if you say anything about my mama%u2019s cooking, you got to put Miss Lidessa Brooks%u2019 name beside there.

TW: Miss Homsley.

PC: Cause they cooked %u2013 and Miss Homsley, Miss Alma Homsley.

TW: Alma Holmsley.

PC: Oh, everybody know them from cooking in the schools.

HB: This is her, right here, when she graduated from A & T.

DW: Oh, wow.

HB: This is her.

TW: The dietary certification for the State.

PC: You wanna look at that closer? You wanna look at that, Joy? Maybe you can write that down and get a copy of that or something %u2013 from the archives, or whatever. I think that was in the African-American %u2013

HB: It may have been.

DW: I%u2019ll use it Afro.

PC: Afro-American.

DW: Okay.

JS: So how did that work %u2013 was there -- how many Negro schools?

TW: Well, one the city.

PC: Cleveland, Hunter %u2013 [everybody talking at once]

HB: And the others was county schools.

TW: Douglas in North ().

PC: And Hunter -- Hunter School.

TW: Hunter School %u2013 that was a school in Flat Rock area.

PC: Right.

TW: Hunter School %u2013 which later turned into a special needs school.

PC: Right. Was that %u2013?

TW: It%u2019s where %u2013 you know where Patton Drive is? Joy, you know where the Administrative Office is?

JS: Uh-huh.

TW: You know, there%u2019s a school in back of it. They use it for storage. There%u2019s a school right in back %u2013 if you go and look, there%u2019s a school %u2013 that was a black school.

PC: Hunter School.

JS: Really?

TW: Hunter School.

JS: Hunter School.

PC: It was an elementary school.

HB: You went to Hunter %u2013 you and Warren both.

PC: When I and Warren went to Hunter, they had a program called %u2013 what was the name of that program I was in? I have no idea %u2013 ( ) something or other. Where they %u2013 you know, I went to Holly Oak Park. [laughter and everybody talking at once] I think it was the first gifted and talented program! [laughter] No, no, I think it was the first gifted and talented program. I think it was kind of a special test they were doing. Anyway, there was a school for a brief period of time out at Holly Oak Park.

HB: And that%u2019s where you went.

PC: That%u2019s where I went.

TW: Was that Miss Mack?

PC: Miss Mack %u2013

HB: Miss Mack was your teacher too?

PC: Miss Mack %u2013 was she your teacher?

HB: She was my first grade teacher.

PC: Get outta here! She was my first grade teacher. [laughter]

DW: This is all coming together!

PC: And Miss Lee.

HB: Miss Lee %u2013 she came after me. But Miss Mack was %u2013 she was the one taught me how to make circles %u2013

TW: Make circles?

HB: Yeah, that%u2019s how she started teaching me how to write, on the line. We started slow. [laughter]

TW: I remember, Peter, it was in that little rec center.

PC: That little rec center %u2013 you wouldn%u2019t think a school was in there. We had four classrooms in that little bitty center.

DW: You said now it%u2019s an exceptional school?

PC: No, it was %u2013

TW: Oh, we%u2019re talking about two different %u2013 she%u2019s thinking about Hunter.

DW: Oh.

TW: Hunter School was the school right in back of the administrative office on Patton Drive. That was part of Flat Rock community. And people in that community went to that school.

PC: What schoolteachers are alive now that were back then? Miss Kitty Hawk is dead, isn%u2019t she? Miss Kitty still alive?

TW: Yeah. Mr. Beam %u2013

HB: Miss Kitty Winston.

PC: Winston, yeah.

HB: Yeah, she%u2019s still living. And Mr. -- James Beam was the principal; he%u2019s still living.

TW: Mr. Beam was the principal; he%u2019s still living.

PC: Oh, you need to talk to James Beam. If you want to get a history of the schools, you need to talk to James Beam, and Miss Winston.

JS: Miss Bridges is a walking history.

PC: Oh, Miss Bridges is gonna tell you everything.

HB: Yeah, she does know from whence came we all. [laughs]

TW: And Mr. Raper.

HB: Cause I think Miss Mack taught Daddy.

TW: What? [noise in background]

PC: Three generations %u2013 no, two generations.

HB: I think Miss Mack taught Daddy.

DW: Wow.

PC: So, write a note here %u2013 if you talk to %u2013 and you gonna talk to Miss Ezra Bridges %u2013 I know you gonna talk to Sam Raper. Just put down Cabaniss School %u2013 ask them about that. Both of them can %u2013 because they probably know more about it that I do %u2013 well, for sure.

HB: We%u2019re just word of mouth %u2013 they were there. [laughter]

JS: Did your --?

TW: Tell them the story about %u2013

PC: Okay now, we were talking about schools. You wanna talk about -- what?

TW: The day care %u2013 the first black day care at Roberts Tabernacle CME.

PC: And y%u2019all wanna know the real story?

DW: No. [laughter and everybody talking at once]

HB: Miss Wesson wasn%u2019t the first school.

PC: No. My grandmother, Lavinia Rogers, was one of the first kindergarten instructors at the first African American kindergarten in Cleveland County. The kindergarten was started by her and a group of white ladies from Central United Methodist Church. Now [pauses] --

HB: It was during World War II.

PC: It was during World War II.

HB: And Mrs. [laughs], the lady talked was Gina Harrill. And she said these white women were interested in having somebody work for them, and that%u2019s why they started this kindergarten, so the women that were working for them would have a place for their children to stay while they were working for them. [several %u201Cohhhh%u2019s%u201D]

PC: So, as opposed to compassion, there might have been an ulterior motive to start a black kindergarten! [laughter] You know, we can%u2019t get nobody to come in here and work in our houses, cause they gonna take care of their children %u2013 well, we gotta find somewhere where they%u2019re children can go, so they can go work in the houses.

HB: Because that was during the war, and the men were %u2013 I guess they wanted to help the women %u2013 moneywise, too.

PC: Yeah, and it was a source of income, so it wasn%u2019t a bad thing. It actually %u2013 I went to %u2013 what was the name of the school? Just Miss Wesson%u2019s kindergarten %u2013

HB: No, it was Roberts Tabernacle %u2013

PC: It was called Roberts Tabernacle Kindergarten.

HB: It became Wesson%u2019s Kindergarten when she built her own place over there on ( ) Street %u2013 it was Wesson then.

TW: But I remember coming and going there in the summertime. It was in the basement of Roberts Tabernacle CME Church. And I remember %u2013 you know what they had for lunch? Tomato sandwiches. It was good.

HB: Yum %u2013 summertime and fresh tomatoes.

TW: And pinto beans. That was nutritious. [laughter] And that was good. Pinto beans and onions. And cornbread.

HB: Some of these writeups in the paper about the integration of schools. Did they have that in the archives of the %u2013

JS: Not actually at the Star. So, those are actually things I can get the date, and then get a copy at the library.

HB: Yeah, I guess the library would have it.

JS: Yeah, oh yeah.

TW: Are those all the articles during the integration?

HB: Yeah, that Daddy saved.

PC: I%u2019d like for you to take a moment and just go through that book. While we%u2019re on the schools, let%u2019s back date, and talk about the first Negro school. All right %u2013 which was Vance Cabaness %u2013 started the first African American school in Cleveland County. He donated the land and built a building. And the first schoolteacher stayed with his family. And the building still stands. And we can arrange a time to go up there if you want to take some pictures and maybe get some wood and make that part of the %u2013 cause you guys are working with Destination Cleveland County, right? And one of the ideas I had is %u2013 they may want to restore that school, and get some funding for that to %u2013 I know at one time, the mayor was interested. I think there was something called Roosevelt Schools %u2013 are you familiar with that?

DW: Oh yeah, uh-huh.

PC: Yeah, the Roosevelt Schools were the land grant schools for the African Americans. And there was some money out there to discover or locate those schools perhaps -- to maybe -- I think it would be an added amenity to the Museum, if as part of your touring here, you could take a brief ride up there. And that would be a draw for African Americans %u2013 hey, we got the Don Gibson %u2013 [laughter] and Earl Scruggs right down %u2013 because you wanna make this %u2013 there%u2019s a monetary motive for doing this, right? Because we wanna make this a vacation destination point, right? Well, then, I%u2019m pretty sure you wanna attract %u2013 have something that would draw a diverse group of people. Well, why not have an African American educational museum, and have it up there at that school, you know.

DW: Yeah, that%u2019d be a great idea.

PC: Especially if it came from you, ( ). [laughter] You can throw that out there. %u201CWhile I was talking to Pete %u2013 you know %u2013 did y%u2019all ever think about doing that?%u201D

DW: Um-hmm.

TW: What? I missed that.

PC: Locating that school and rebuilding it.

TW: The Cabaniss School?

PC: Uh-huh, and turning it into an educational %u2013

TW: Because of the historical %u2013

PC: Yeah, as a historical place, and as a museum. You know, they could put the history of African American educational system in America.

TW: That would be great.

PC: That might even get them national %u2013

DW: Actually, there is a %u2013 well, just as an aside %u2013 there%u2019s a national %u2013 the National Historic Registry %u2013 you can put the school on that, and they have a website, and maybe they could help restore it. Well, not fully restore the schools, but get some acknowledgement %u2013 I think some funding to do something.

HB: I saw that on one of the educational stations %u2013 some school in South Carolina that they were restoring. I saw that on one of the educational stations.

DW: Was Vance Cabaniss %u2013 is that your grandfather, great-grandfather?

PC: That was m grandfather %u2013 my great-grandfather. So there was Vance, Walter, Ray, Pete. [laughter]

HB: Four generations.

DW: Okay.

TW: You say you think this is Vance, his wife?

HB: I think that%u2019s Lizzie.

PC: His wife?

HB: Yeah, Vance%u2019s.

PC: Well, fantastic.

DW: Lizzie Cabaniss?

PC: This is old Grandma Lizzie. Oh, she look like a grandmamma too! Oh, oh, ooh! [everybody talking at once]

TW: She looks like she%u2019s Indian.

HB: Yeah, they say she had some Indian blood in her.

PC: Wonder () Hey, you think I%u2019m kidding? You look at this %u2013 you wanna straighten up now! [laughter]

TW: Oh, she wasn%u2019t playing.

PC: No, she wasn%u2019t playing, was she?

HB: No, they were serious back in them days.

JS: If she told to sit down, you %u2013 [everybody talking at once]

PC: She didn%u2019t have to tell you to sit down! But she does look like she%u2019s got some Indian in her.

TW: And that%u2019s Rayfield -- the other brother that couldn%u2019t make it today %u2013 that%u2019s him.

DW: The little one?

TW: That%u2019s Rayfield %u2013 the one that integrated Shelby High.

DW: Oh, Okay. Is that your daddy, granddaddy %u2013

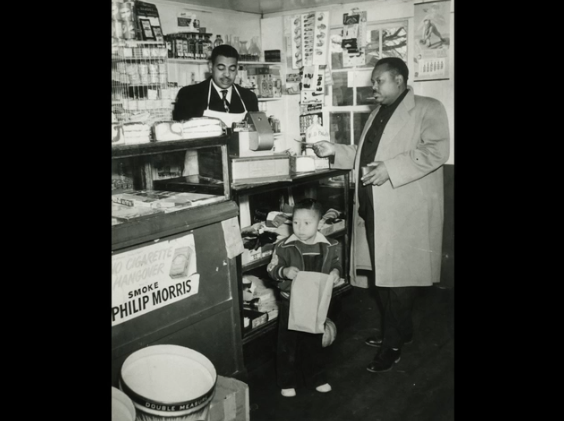

TW: That%u2019s my grandfather. That%u2019s Pete%u2019s dad, and my mother%u2019s father. That%u2019s Ray Cabaniss. And that%u2019s the store. See, when they came back, they went to Connecticut and worked in the factory during World World II %u2013

HB: The defense plant.

TW: The defense plant %u2013 during the forties, and %u2013 for two years %u2013 and Mom and her sister were taken care of by her their maternal grandmother while they went up North. And after they came back, what he saved, he built the store. Right, Mom?

DW: Oh, okay.

HB: After a period of time, the store became his insurance office, right?

TW: Right.

DW: And with the %u2013 I don%u2019t know where to start with [laughs] questions about the schools %u2013 cause I don%u2019t know a whole lot. I did -- from just people telling me %u2013 that these were some of the black schools. Like seven black schools %u2013

TW: Green Bethel %u2013 that%u2019s where my dad went. Cleveland School %u2013 that%u2019s where Mom. Compact is in Kings Mountain. Lawndale School %u2013 was that the elementary?

PC: Douglas.

HB: Douglas.

TW: Douglas. Lawndale and Douglas the same?

HB: Well, I guess Lawndale may have been an elementary school, but Douglas was the high school.

TW: High school. Then Camp School was going south. Kings Mountain school?

HB: Davidson.

TW: Davidson, okay. Crest and Burns, were they around?

HB: No, no, no %u2013 Crest and Burns came when integration.

TW: Integration. But there was Maple Springs.

HB: That was an elementary school.

TW: That was Maple Springs Elementary.

HB: But the high schools weren%u2019t called Crest and Burns, they were called something else. They all had whole neighborhood schools like we did. Like Piedmont, and stuff like that, were the high white schools.

TW: So all the black schools -- what are they?

PC: They%u2019re missing one.

TW: Which one?

PC: Northside.

HB: No, that was integrated. That%u2019s integration.

PC: The teachers was integrated. Wasn%u2019t no white kids go to Northside. Not when I went, not the first year.

TW: All those kids over there in Roberts Dale, at the projects.

HB: Okay, I wasn%u2019t here then, so %u2013

PC: It probably wasn%u2019t meant to be a black school, but it ended up being a black school.

DW: Oh, Okay.

TW: What we call North Shelby, Joy %u2013 that used to be all %u2013 That%u2019s called Northside School. Yeah, all the kids that went there %u2013

PC: Now, Mr. Beam was the principal at Northside, too.

DW: Huh, okay.

PC: Cause I got a lot of spankings over there.

PC: No, that was third grade. Didn%u2019t get no spankings in high school. Spanking days were over. [laughter]

DW: Are any of these schools still around %u2013 the buildings still around?

PC: Most of %u2018em.

HB: Yeah, Cleveland School%u2019s still around.

PC: Hudson and Webber Street.

HB: Hudson and Webber Street, and Green Bethel is still up there in Boiling Springs.

PC: Douglas is still %u2013 it%u2019s Lawndale Baptist Church. [everybody talking at once]

HB: And so is Washington School; it%u2019s a church too.

PC: What about Camp?

TW: We forgot about ( ). Yeah, Camp School.

PC: Green Bethel is a church now, too.

HB: No, no. The school%u2019s still there.

PC: It%u2019s still there? Yes, multiple schools are still here.

HB: Camp was being used as a church for somebody, wasn%u2019t it?

TW: No, Camp for a while was the Life Enrichment Center.

HB: Okay. Isn%u2019t that where Lois and --? No, no, no. What%u2019s near the church that Lois and her husband pastor?

TW: Lois who?

HB: Covington.

TW: Covington? New Life.

HB: New Life. It%u2019s on the highway. It%u2019s on 18.

TW: Yeah, it%u2019s on 18. On Shoal Creek. But I%u2019m trying to think if there was another %u2013 now Hunter School was a black school. That was in the Flat Rock community %u2013 it was an elementary school.

DW: Was this %u2013 even after the schools were integrated?

TW: It was before.

DW: Before, Okay.

HB: What did it become after integration?

TW: It was Hunter School, but it became a special needs school.

PC: Now, you know %u2013 now, you have to date that integration as a time line there right. There%u2019s your documented, historical, written date of integration, and then there%u2019s %u201Cwhen did integration really happen?%u201D

JS: So, walk me through that -- walk us through that in Cleveland County.

PC: Well, in 1958, the Supreme Court ruled that %u201Cseparate but equal%u201D was not the law of the land, was no longer the law of the land. Was that called the Dred Scott decision? No --

TW: Brown --

PC: -- that was Brown vs. Board of Education.

TW: 1955.

PC: Was it %u201955?

TW: Um-hmm.

PC: Okay. And in 1963, the schools in Cleveland County were still segregated. And my father %u2013 I remember him saying that the white kids at Shelby High %u2013 each one of them had a microscope in their biology classes, and the black kids shared microscopes. And there was just %u2013 the schools were separate, but by no leap of the imagination were they equal. And he felt like the African American kids in Cleveland County deserved an equal education, and the only way to achieve that would be to integrate the schools. So he contacted the NAACP, and they assigned a lawyer to him, and he put in for a transfer. And the NAACP, from what I recall, they did everything very methodically. They really %u2013 even with Rosa Parks %u2013 they always tried to work within the law, and they%u2019d let you kinda make the mistake. So he put in for a transfer, and my brother was denied a transfer to the schools. One of the reasons he was denied a transfer was that they said he wore glasses. [laughter] Another reason is that well, socially it wouldn%u2019t work out for him, cause he would be the only black kid there %u2013 he%u2019d be better off in a black school. When they repeatedly denied his transfers, that%u2019s when he brought a lawsuit %u2013 with the help of attorneys from the NAACP. During that time our house was fire-bombed %u2013 a cross was burned in front of it. I distinctly remember the night it was fire-bombed. I was sitting in front of the TV with my legs crossed, watching the Ed Sullivan Show, as millions of households across America was doing. So from a society standpoint, we all had that in common. But from an African American community standpoint, my night was rudely disturbed when we got a phone call. And the lady was screaming on the phone and said %u201CMargaret, you better run, you better run! They throwed something in your yard!%u201D And I remember my momma grabbing me, and dragging me out the back porch, and down the back street to my aunt%u2019s house, because our house had been fire-bombed.

DW: Fire-bombed like a fire %u2013

PC: Like a fire-bomb %u2013 it%u2019s in the papers. Okay, now %u2013

HB: It%u2019s in one of these articles here.

PC: Yeah, there is an article in there about it.

TW: Cause during that time, my mom and dad %u2013 my dad was in the military %u2013 and they would send articles over to Japan to let Mom know what was going on. And Mom would keep %u2018em.

DW: How many siblings are there?

HB: Five.

DW: Five.

TW: Here they are, right here %u2013 well, minus Pete. [laughter]

PC: Well, actually what happened is that after Daddy had four kids, and he looked at them, he looked at his wife and said %u201CMargaret, I know we can do better than this!%u201D [laughter]

[everybody talking at once]

TW: Tell me your name again.

DW: Dwanna.

TW: Dwanna, I think it%u2019s so interesting %u2013 you have two generations here. You have Pete%u2019s perspective on integration and what%u2019s happening, but my mom was in it, and I think my mother has a really interesting perspective. I want Momma to share what you%u2019ve shared with me %u2013 I%u2019ll help you. Momma%u2019s kinda shy sometimes.

HB: What do you want me to say? [laughing]

TW: You remember you thought you didn%u2019t like anything, cause you felt like her education was superior because the teachers really put their heart %u2013

HB: They did. They were very caring, very, very caring. And I know I told her this once %u2013 I went to school %u2013 after I graduated from high school, I went to a school in Providence, Rhode Island.

TW: She went to Johnson and Wales.

[inteviewers %u201Cohhh%u201D]

HB: And that was my first school with white people. And I thought %u2013 we were always taught %u2013 oh, we always thought that they were smarter than we were, but when I went to school with them, I thought no, I was just as smart as they were.

TW: It was Johnson and Wales, it was in Rhode Island, the business school, and Momma pulled out her yearbook from up there.

DW: Wow. So you %u2013 what do you think helped to make it so much %u2013 what made the schools better from your perspective than %u2013

HB: Well, they had more equipment, but sometimes the classroom wasn%u2019t that different. You know, the teachers were %u2013 it depended on %u2013 some teachers were kinder to you than other teachers, and some teachers were %u2013 if you wanted it, you get it yourself. Some teachers were %u2013 in the black schools, those teachers made sure that you knew what they were trying to teach you. But sometimes, in the white schools, they didn%u2019t take that much time with you, I don%u2019t think. But, if you wanted to do what you wanted to do %u2013 if they saw that you were interested in learning, they would help you a little more. All ( ) are so interesting, I guess that%u2019s what you would say.

DW: Were you one of the only black students?

HB: I think there was another. Would you say %u2013

TW: I think there was about four.

HB: Four, I guess. I know %u2013

TW: That%u2019s Providence, Rhode Island in 1955. Momma was in %u2013 what was it %u2013 typing class?

HB: See, they just had the senior classes individual pictures, but they took pictures of classes %u2013 each class that you%u2019re in, so I was in one of the pictures of one of the typing classes.

DW: Did you ever experience any different treatment from other students?

HB: Huh-uh.

TW: Not in Rhode Island.

HB: Because the next semester, I wanted to change to office machines, and my teacher told me to stay in bookkeeping %u2013 I didn%u2019t especially like at that time %u2013 continue to do accounting would be more opportunity for you to have a better job if you just did office. That%u2019s when all this electronic machinery, and data processing %u2013 all that was coming in. And that%u2019s what I wanted to do -- I wanted to get into that. And she told me to stay with the accounting department. I thought that was kinda interesting, her %u2013

DW: And did you stay in touch with either the students growing up here, or with the students at this school %u2013 Johnson and %u2013

HB: No, I didn%u2019t really know any of the students, I just went to school there. You know, being black, you didn%u2019t make too much social contact with the students, so I just went to school there.

JS: Tell me about this cotillion %u2013 you had the first %u2013

HB: Oh, that was [laughs] my sixteenth birthday %u2013 it was just a party.

PC: Sweet sixteen. It was more than a party %u2013 it was the party! [laughter]

HB: No, that was just a party.

PC: You look at that picture and tell me if that looks like %u201Cjust a party.%u201D [laughter]

JS: That%u2019s more people than come to any party that I%u2019ve had.

TW: I mean, they%u2019re all dressed up %u2013 looks like a %u201Ccoming out.%u201D She was sixteen, and you%u2019re daddy put that on for you, didn%u2019t he? Did he have live entertainment?

HB: No, I think we just had regular records.

TW: Records? Forty-five records? They was spinning little %u2013 [laughter]

HB: Yeah, we all wore our best dresses to that.

DW: Yeah. Was this at the Armory?

HB: No, it was at the old Holly Oak Park, Holly Oak Park.

DW: Ohhh.

HB: And see, he had his first dances at the old Holly Oak Park %u2013 but no, he started at the Armory. And he had those big entertainers to come into town, he would have it at the Armory. Then when the local dance bands came, he%u2019d have it at Holly Oak Park.

TW: Didn%u2019t he have %u2013 the man that sang %u201CSitting on the Dock of the Bay?%u201D

PC: Otis Redding.

TW: Yeah, Otis Redding.

HB: He came to %u2013 those people would come to the Armory.

TW: That was special %u2013 people looked forward to stuff like that.

DW: People%u2019s shoes were shining %u2013 looking sharp! [laughter]

PC: They ain%u2019t wearing no baggies, are they?

[everybody agrees]

DW: So did this happen %u2013 did your other sister have %u2013

HB: Yeah, they gave her one too %u2013 when she turned sixteen. And then when %u2013 you all %u2013 they gave you and Tanzy a big party too.

PC: Yeah, we had a big party.

TW: 1973.

JS: Now, you said this was the first African American %u201CSweet Sixteen%u201D party.

PC: I don%u2019t know that to be true. [laughter] But you could say it.

TW: You could say %u201Clifestyle of the %u2013 %u201C that was just the %u2013

PC: It would probably be a good bet that it was.

DW: What is your %u2013?

PC: ( ) a dance for a young girl. A young, beautiful lady.

HB: Oh, okay. He knows how to put those words together [laughter].

PC: You could call it ( ).

HB: But the first %u2013

PC: Black ( ) [laughter]

HB: They did %u2013 now, the Shelby Women%u2019s Club gave a %u2013 they did a %u2013 what was it they did the next year, when I graduated from high school? They had a %u2013 what did they call it? A cotillion?

[several people say %u201Cdebutante ball%u201D]

HB: Debutante Ball? Debutante, debutantes.

TW: Shelby Negro Women%u2019s Club. That%u2019s the oldest black organization in the county, isn%u2019t it? Started in 19--, before 1920.

DW: And they would have an event like a debutante ball?

HB: Yeah, they had the first one %u2013 I graduated in 1953 %u2013 the first one they had was in 1954, so you can talk to some of the %u2013 Miss Kitty Winston probably could tell you %u2013 she%u2019s in the Shelby Negro Women%u2019s Club, and she would love to talk about that.

DW: Kitty Winston?

HB: Uh-hmm.

JS: I want to back up just a moment %u2013 when your father was able to actually go into an integrated school, did he talk about that?

PC: Oh, you have to call my brother %u2013 he can tell you some stories.

JS: Okay.

PC: You mean, when my brother was able to go? Or %u2013 when you saying?

JS: He %u2013

PC: Did he talk about %u2013 I don%u2019t recall %u2013 Helen?

HB: You wanting to know if he had any encounters with the school itself when he %u2013

JS: Yeah, what was his first day of school like %u2013 at an integrated school?

HB: You%u2019ll have to ask Ray, cause I %u2013

PC: Yeah. I do know one thing Rayfield told me that the first time he felt like a man is when he graduated, and Daddy looked at him, and said %u201CWe did it, didn%u2019t we.%u201D [laughter]

TW: Wow.

HB: He was the first boy %u2013 there were three or four girls went with him. [telephone rings]

TW: He was the first man.

HB: And his daddy was the one that instigated them getting there. He was the one that went through all this to get them there.

TW: And Severne Budd was one of those women.

PC: And the lady across the street %u2013 didn%u2019t she go? Miss Watson? Arnie Watson%u2019s daughter?

HB: Char %u2013

PC: Charleen?

HB: Charlene. I don%u2019t know.

PC: We%u2019ll have to call Rayfield, cause he was the one. And that%u2019s carrying a lot of weight. I mean, there%u2019s been stories about %u201Cthose girls that integrated Little Rock,%u201D or %u201Cthe kids that integrated Little Rock,%u201D right? And the effect %u2013 and some of it hadn%u2019t been so good.

DW: Yeah.

PC: And that%u2019s a lotta weight to carry on %u2013 it%u2019s like a whole race %u2013 both races %u2013 the whites are looking for you to fail, and the blacks are looking for you to succeed, praying that you don%u2019t fail.

DW: Did you %u2013 after your house was fire-bombed %u2013 how did you feel, living there after? Do you remember being afraid?

PC: I wasn%u2019t afraid because I had a lot of confidence in my father.

DW: Um-hmm.

PC: I remember that people was following %u2013 it looked like -- his every move. When he would get home, people would call the house, and they would say %u2013 they would ask for my father. I remember one night he answered the phone, and they asked him %u201Cwhat color casket do you want?%u201D And he said %u201Cthe same color your momma had.%u201D [laughter]

TW: He wasn%u2019t afraid! Man.

PC: Papa Strong used to sit on the porch with a gun, with a rifle, or shotgun, or

something. That was our next-door neighbor. So you have to talk to Miss Jenny Ree too.

DW: You%u2019re saying %u201CReeds?%u201D

HB: Jenny Ree %u2013 that%u2019s her middle name %u2013 Jenny Ree.

PC: ( ).

HB: Yeah, what%u2019s her name now, Bell? Jenny Ree Bell.

PC: She married?

HB: Yeah, she married a Bell. He died. But she married James Bell.

JS: I imagine -- from looking at your file %u2013 people also were looking very closely at you. What was it like being %u2013?

PC: I was five years old. I%u2019m %u201CLittle Petey.%u201D [laughter] That%u2019s what they still call me.

HB: I guess Warren could tell them.

PC: I don%u2019t, I don%u2019t %u2013 I remember when JFK was shot, and Momma %u2013 I was playing with ( ), and Momma said %u201Ccome inside, cause something bad might happen to you, cause the president%u2019s been shot.%u201D But I don%u2019t have any of those sociological viewpoints, that an older child might have. I didn%u2019t feel put down, or left out %u2013 I was a child, had the emotions of a child, and the concept of society that a five-year-old child would have, so -- no, in that regards -- I can%u2019t give any deep, profound insight into how it felt. I was scared, running down the back street, but as a child, as long as you have your parents with you, you probably aren%u2019t as afraid %u2013 as a thirteen-year-old child might be. Because your mind isn%u2019t developed to the point where you can judge, or even think about consequences.

HB: I guess Rayfield could tell them what %u2013

PC: Oh, Rayfield and Warren %u2013 they were in the house all through. There was three boys there %u2013 and Rayfield and Warren can tell you %u2013 express some of their feelings. And you may get some anger, some things of that nature.

DW: So by the time you both came along, what was it like to be in the schools? [phone rings and laughter]

PC: It was great for me.

DW: How so?

PC: That was in the %u2013 I was in high school in the seventies. So that was right after the riots, and that was %u2013 there is a historical term for that time period for blacks %u2013 help me out with it, Dwanna; what is it? It was like a brief period of enlightenment, right? I mean, you had the Black Power movement, you had the afros, you know -- %u201Csay it loud, I%u2019m black and I%u2019m proud,%u201D and it was pretty much like %u201Chey, I%u2019m still here, man.%u201D And that%u2019s when we were %u2013 I don%u2019t want to say %u201Cfull of ourselves%u201D %u2013 that%u2019s when black consciousness, you know, you were allowed to have such a thing as black consciousness, right? You could actually stand up and say %u201Cno!%u201D

DW: Um-hmm. So did you have %u2013 by that point, were schools fairly integrated, were the teachers integrated?

PC: Oh, we were integrated big time. You know, except for lunch period, which even now %u2013

JS: Yeah, you definitely still see %u201Cwhite,%u201D %u201Cblack%u201D %u2013

HB: Yeah, they still separate %u2013 we still separate ourselves %u2013 even now. [laughs]

PC: You know, it was during that period where they had parity elections. You remember that? Did you do any reading on that %u2013 parity elections?

DW: Um-hmm.

PC: Okay. Where if there was a black president, the vice president would be the %u2013 even if the black guy got the most votes, the next one would be a white guy; and if a white guy won, the black guy would be %u2013

TW: Was this at Shelby High?

PC: Um-hmm %u2013 they had parity elections.

HB: If the black guy was black, then the vice would be black, right?

PC: Um-hmm %u2013 would be white.

HB: One black, one white.

PC: One black, one white.

NIKAO WALLACE: That still goes on with the homecoming queens, and stuff.

HB: Is that the way it still is, Nikao?

NW: Well, the homecoming queens and stuff, they don%u2019t. I think up until a couple of years ago, Shelby %u2013 they were white/black every year.

DW: Is that where just the all black, white --?

NW: Yeah, and I think the only reason it stopped was there wasn%u2019t a white homecoming queen with a nominee, so %u2013

PC: That%u2019s when they stopped having homecoming queen?

NW: Well, no, no, they didn%u2019t stop having %u2018em, but they -- it was just like a black girl two years in a row. And, when I was going, it was always white/black.

HB: They don%u2019t vote on them? Don%u2019t they elect them?

NW: Yeah, they vote, but I mean you %u2013 nobody counted %u2013 the teachers, nobody counted them. I just thought it was weird. Maybe they did vote for %u2018em; maybe they did get the most. But I thought [laughter] it was just weird, you know %u2013 every other year, they%u2019d be a different %u2013

HB: Oh, one year she%u2019d be black; next year she%u2019d be white.

NW: Yeah.

HB: [laughs] So the teachers were doing the counting, huh? [laughter]

NW: Yeah.

TW: I remember Rayfield sharing with me %u2013 and it was in his yearbook %u2013 one person said %u201Cif it wasn%u2019t for you, Rayfield, I wouldn%u2019t have passed Geometry, Calculus,%u201D or something like that.

HB: White person?

TW: Um-hmm, it was a white person. Cause he went on to school to be a %u2013 what, chemist?

HB: Uh-huh.

TW: He went %u2013 Rayfield went to school %u2013 where did he %u2013 at Lane College, and he studied out in Lincoln, Nebraska, and then he got %u2013

HB: He changed to Lincoln.

TW: -- a degree in chemistry.

PC: Yeah, my brother, Rayfield, was very, very smart.

HB: He is.

PC: He%u2019s a very smart man.

DW: He lives in Charlotte?

PC: He lives in Charlotte. Sharp as a tack.

HB: You know he knows it.

PC: But I do encourage you %u2013 we%u2019ll make sure you get his phone number.

HB: He had planned to come up today, but something happened.

PC: Oh, he can tell it. You may be able to even to draw some things out of him, because you ask very probing questions, thoughtful ( ) questions.

TW: Unless you can put him on speaker phone %u2013 you don%u2019t have a speaker phone, do you?

HB: Huh-uh.

TW: Cause I have a speaker phone on my cell phone.

PC: It has a speaker phone with the phone upstairs. We could bring it down here, it has a pretty good ( ) to it. You know them little phones upstairs?

HB: There%u2019s one in the --

TW: I mean, does it detach from the %u2013

PC: No, no, no. The handheld %u2013 you put it on %u201Cspeaker%u201D and it%u2019s pretty good. Get the phone from the bedroom %u2013 Frank%u2019s bedroom upstairs, and we%u2019ll put it on %u201Cspeaker,%u201D if we wanna try to call him.

TW: Detach it from the wall?

PC: No, no, no, no, no, no, no %u2013 it%u2019s a portable handheld thing.

DW: So, we were talking %u2013 Joy and I were talking a little bit yesterday, about this %u201Cparity%u201D %u2013 and Joy came across this picture of Miss Black Cleveland County %u2013

JS: Yeah, um-hmm.

DW: -- has that always gone one?

PC: I don%u2019t know a thing about it. Helen?

HB: What is that?

PC: You know anything about Miss Black Cleveland County?

HB: Yeah, they did have that, but it was %u2013 they did have that a couple of years %u2013 Miss Black Cleveland County. But%u2026I don%u2019t remember anything about it, but do I remember that they did have it.

TW: This doesn%u2019t have a speaker. [she and Pete discuss the phone]

PC: I think it does have %u2013 I could be mistaken. Let me see %u2013

DW: Oh, I was gonna ask you, Nikao %u2013 what was school like for you?

NW: Oh, it was cool %u2013 I enjoyed it, when I went there. I think Shelby High is like %u2013 over sixty percent black now, or something like that, so the roles are pretty much reversed.

DW: What%u2019s the percentage of blacks? It%u2019s not that high for the county, is it?

NW: No, it%u2019s not for the county %u2013 I think there%u2019s more of the white students are in the county schools and stuff. I%u2019m pretty sure %u2013 I think there%u2019s more blacks than whites in Shelby High.

DW: Okay.

PC: Is this charged?

DW: Then that%u2019s probably why the %u2013 you were saying about Kings Mountain %u2013

PC: Oh, this isn%u2019t charged up. It wasn%u2019t in the cradle?

[two conversations at once]

TW: I have a speaker on my cell phone.

PC: Okay, a good one? This has a speaker too %u2013 it%u2019s pretty good.

HB: There%u2019s another one in the other room.

PC: While it%u2019s on my mind %u2013 the Negro Fair. Have you heard about that?

DW: Yes, yes. Had that on the list of questions. [laughs]

HB: That was nice %u2013 it was nice.

DW: Mrs. Barrow, I%u2019ll ask you, since you%u2019re here %u2013 I came across %u2013 I think this is you %u2013 did you work for First National Bank?

HB: Yeah, yeah, that%u2019s me. [laughs]

DW: Oh, Okay. What was it like working at the bank?

HB: It was different %u2013 I came here %u2013 when I came here, I had worked in a bank in Maryland.

TW: ( ) She was the second black who worked at First National Bank.

HB: Well, they were nice, but %u2013 as time grew, it became better.

SW: I know I can%u2019t walk into the bank %u2013 %u201Cnow you Helen%u2019s son %u2013 I mean grandson.%u201D Everybody %u2013 she left her mark.

DW: Yeah %u2013 how long did you work there?

HB: Over twenty-five years. ( ) One of your reporters came in, and people were very nice to %u2013 you know, the customers were very nice to me, and he came in and said %u201Cwe want to write a article about you as a teller, or something,%u201D and I told him no, I didn%u2019t want to stand out and make them uncomfortable %u2013 no, don%u2019t do that.

DW: Yeah.

HB: But he did, he came up when I was there and said he wanted to write a story about me as a teller for First National Bank %u2013 now, don%u2019t put that down, cause nobody knows that -- I didn%u2019t publicize it %u2013

TW: It%u2019s on %u201Crecord%u201D, though. [laughter]

DW: Well, we can take that out %u2013 [everybody talking at once]

HB: It%u2019s just something that I%u2019m saying, cause I never told them %u2013 he came to me twice and said he wanted to do a article about me. You have seen it in articles lately, that they do recognize tellers that, you know %u2013

TW: Was this for the Shelby Star?

HB: The Shelby Star %u2013 and this was years ago, that he came by.

TW: The seventies?

HB: Yeah, maybe the eighties %u2013 between eighties and nineties, something like that. He came in twice and asked me if he could write a story about me, as a teller. I told him no.

DW: Awww. [laughter]

HB: Because I didn%u2019t %u2013 I didn%u2019t want them to feel like %u2013 you know, I was thinking more of the other person than I was thinking of myself. But I thought it was nice of him to ask.

DW: Yeah %u2013 but I%u2019m sure you have great stories to tell. Stories to help remember what it was like.

TW: I remember %u2013 she was more than a teller up there %u2013 I mean she was social worker, advocate. A lot of people stopped banking there when she [laughs], because they knew Momma would take care. I think a little bit of that spilled over with everybody in the family, cause Momma wanted to make sure people%u2019s business was taken care of. Sort of a quiet %u2013 quiet missionary.

HB: You know, there were ( ) that would come in %u2013 they couldn%u2019t read, and they couldn%u2019t write, and you%u2019d take more time with them, and show them what they should do, and how to do this, and how to do that, and you%u2019d be a little more concerned about making sure that they took care of their money in the right way, and stuff like that.

DW: Did you -- that was the only bank for everybody in the county?

HB: No, there was another bank.

DW: Oh, Okay.

HB: The first two banks were First National and Union Trust.

DW: Okay.

HB: Then there was a company came in and bought Union Trust -- no, no, Northwestern bought them %u2013 Northwestern came in as Northwestern. But it was %u2013

TW: NCNB?

HB: No, no. It ended up being BB&T. That%u2019s what it is now, BB&T. But there were two or three other banks that bought them before it became BB&T. But First National has always %u2013 nobody has ever %u2013 they may have tried to buy First National, but nobody has %u2013 First National has been First National since it started. And it was 1874, something like that. And %u2013 now far as been retirement, retirement was very nice %u2013 they were very nice to me %u2013 after %u2013 after -- when you first go in, there%u2019s a cool %u2013

TW: Transition. [laughter]

HB: You don%u2019t feel exactly like you gonna %u2013 you know, you%u2019re there and they%u2019re there, but they finally came over, and they were extra nice.

DW: How long did that take for them to kind of -- get comfortable?

HB: Oh, I guess for me, [laughing] a couple of years %u2013 I don%u2019t know. You could feel it, but you don%u2019t feel it. You just go ahead and do what you have to do, and as they see how you progress and how you do handle yourself, that makes them become more confident in you. I guess it%u2019s something like these people now with Obama [laughs] %u2013

DW: Yeah.

HB: -- they%u2019re giving him a rough time %u2013 but I didn%u2019t have that kind of time, but you can compare yourself to %u2013 it%u2019s a change, it%u2019s a difference between %u2013 because sometimes now when they%u2019re saying something about him, it%u2019s not because they don%u2019t really like him, it%u2019s because he%u2019s not doing it like they think it should be done. So that%u2019s the way I feel about it.

DW: I%u2019m sure you opened the door for other people, so --

HB: Yeah.

DW: -- they appreciated it.

TW: There was quite a number. After a while, you were the only black there for how long, Momma?

HB: Oh, a long period of time.

DW: Only.

HB: Cause the first black, she had a little problem with the -- and they had to let her go. I said %u201Cthank you, thank you, thank you%u201D that I able to retire here. Sometime you look at it and you say sometime or another somebody%u2019s gonna try and find something to keep you from getting ( ). So I said %u2013 when it was time for me to go %u2013 thank you, I%u2019m retiring. Cause I was the first one to retire. I was glad %u2013

TW: First black to retire from First National?

HB: Um-hmm, uh-hmm, first black teller, first black teller.

DW: A lot of firsts! [laughs] Wow, wow. So I was talking with %u2013 this is in Charlotte -- but I was talking with a woman a few months ago, and she was the first black salesperson, and she was saying %u2013 which I had never really thought about, because by the time I came up in their stores and stuff, things were much different than now %u2013 they look probably probably forty or fifty years ago, but did they have like black maids work in different stores, or black butlers %u2013

TW: Janitors, or custodians?

DW: Yeah.

HB: Well, the custodians were men, they didn%u2019t have any women %u2013 they were all men.

DW: Oh. Oh. So if you were a maid, you would just work in someone%u2019s house?

HB: Um-hmm. But the First National never had a woman do maid work. They always had men to do that %u2013 black men.

DW: Did you feel that %u2013 were there any tensions between the janitors and you being the first black teller, and just the positions?

HB: Huh-uh. No, because %u2013 I guess because my grandpa was a %u2013 Papa Walt worked at the bank, too. And he was their bank chauffer. Now I don%u2019t know whether %u2013 I don%u2019t think Papa did any cleaning, I don%u2019t think he did any cleaning, but they had a black crew to do the cleaning. But my grandfather worked for the First National Bank, too.

DW: A chauffer?

HB: Yeah, he worked there %u2013 I don%u2019t know what he did! [laughter]

DW: It is different.

PC: And he took the money from Lawndale to Shelby.

DW: Oh, Okay.

HB: Yeah, he was the courier, he was the courier.

PC: Courier, yeah.

HB: He was also %u2013 the courier %u2013 but he was also %u2013 if old lady Blanton had somewhere to go, he would %u2013 you know -- he was a chauffer, too.

DW: Wow.

PC: ( )

DW: That%u2019s a big job, that they trusted him with the money [laughs].

PC: Well, now, talking about a chauffer, wasn%u2019t %u2013 now I could be wrong, but wasn%u2019t A. L., Uncle A. L., old Mrs. ( ) chauffer?

HB: No, he was chauffer for ( ) Hoey.

PC: Oh, Governor Hoey?

HB: Um-hmm.

DW: Huh.

TW: Who %u2013 A. L. Bailey?

PC: Um-hmm.

HB: Yeah, he worked at Hoeys.

TW: Huh.

PC: So, there%u2019s two governors from Cleveland County.

HB: Yeah.

PC: Okay. You know, so there%u2019s two governors from Cleveland County.

HB: Governor Hoey, and Governor Max Gardner.

DW: So, what would be %u2013 I do wanna go back to the schools a little bit, if that%u2019s okay %u2013 but, what were good jobs for black people in the county %u2013 then or even now %u2013 what would be considered good jobs?

HB: Janitors and maids. [laughs]

TW: Well, you would find school teachers.

HB: Yeah, school teachers would be the number one thing that %u2013 cause that was one thing I said when I graduated from high school, I was not gonna be a school teacher. [laughter]

TW: They just primed you for that -- schoolteachers and %u2013

HB: Cause my girl friend was a school teacher %u2013 she went to school to be a school teacher.

TW: Mrs. Beam?

HB: Um-hmm.

TW: And your sister.

HB: Um-hmm, my sister%u2019s a school teacher. And I was determined I was not gonna be a school teacher. [laughter]

DW: Did you know what you wanted to do?

HB: Oh, well what I started %u2013 I started out as %u2013 I wanted to be a social worker. I wanted to be a social worker. But I ended up working in accounting, in bookkeeping.

DW: That sounds like what your daughter was saying, you got a little bit of the social worker [laughs] out %u2013

HB: Well, I grew up wanting to be one of those missionaries who go into foreign countries. You know how little girls have all these kinda dreams %u2013 they wanna go out and be a missionary and do things, so I really did want to be a missionary. But, black folks didn%u2019t go to foreign countries to be a missionary, but I did, I really wanted to be a missionary [laughs].

DW: Wow.

HB: So I%u2019m still doing, touching on some of the stuff there. Come to find out, it%u2019s better to do things locally than to want to go way out somewhere.

DW: Yeah. Take care of home first? [laughs]

HB: Yeah, I know but %u2013 as I say -- you know, when you%u2019re young, you want to go to foreign places and do things %u2013 I wanted to be a missionary in Africa or something like that. [laughs]

TW: Well, you married a military man.

HB: [laughs] Oh, yeah I did. But that was far from being a missionary! [laughter]

TW: Home missions!

HB: That was quite the opposite of being a missionary %u2013 being a military wife, I tell you that!

TW: Yeah, home missionary.

HB: They would send %u2013 you%u2019d be %u2013 we did travel with him, so we were in Japan, and he would go %u2013 they%u2019d take us to Japan, then they%u2019d send him to %u2013

TW: India.

HB: India, or somewhere %u2013 I%u2019d say %u201Cnow he brought us over here, and here we sit here in the house.%u201D [laughter] But that%u2019s the case %u2013 we did %u2013 we went everywhere. We traveled a lot with him. When he retired, we came back to Shelby. We stayed in Washington, D. C. about ten years %u2013 eight or ten years, didn%u2019t we?

TW: A good eight years.

HB: Of course, he was with the President. He was appointed to one of the President%u2019s sections there.

JS: So you traveled with him with the military, then came back and worked at First National, and retired at First National?

HB: Um-hmm.

DW: So was going in the military a option for a black man?

HB: Yeah, um-hmm. Well, see %u2013 when he went in, first he was drafted %u2013 that%u2019s when they had the draft %u2013 he was drafted. And when he came out, he reenlisted and volunteered for the Air Force. Cause he said he wanted to go into the %u2013 I was a military %u2013 Air Force military wife the whole time, cause when we got married, he was in the Air Force.

JS: Was that like the best option for black men at that time? Military service?

HB: He thought so. Course that was in the fifties %u2013 I got married in the fifties. So he thought that was better %u2013 he%u2019d have better chances of progressing. Cause he did %u2013 when he got out of the service, he went to Washington, D. C., and he worked at the Pentagon for a period of time, and he decided he didn%u2019t like Washington, D. C. He wanted to go back into the Air Force. That%u2019s what we %u2013 that%u2019s what us did! [laughter] And when he came back here, he retired %u2013 he worked at PP&G till he retired from PP&G. So now he%u2019s a wood carver %u2013 see these flowers here %u2013 that%u2019s what he does now.

DW: Oh. Wow, that%u2019s nice.

TW: ( ) did a piece on him.

JS: Okay.

HB: The Star has done a write-up on him. He does %u2013 mostly, I guess %u2013 his walking canes.

JS: Okay. Yeah.

DW: What%u2019s PP&G?

TW: Pittsburgh Plate and Glass.

DW: Oh, Okay.

TW: PPG.

HB: What did I say? PP&G. [laughs]

TW: Pittsburgh Plate and Glass. They wind fiberglass.

DW: Are any blacks in like sales positions in the stores downtown?

TW: Yes. My aunt, Corine. She%u2019s one of the first black retailers I know of. She worked for a Jewish family %u2013 Cohen%u2019s?

PC: Cohen%u2019s.

TW: C-O-H-E-N. Uptown.

PC: Yeah, you have to put her down, too. She%u2019s 94, 92?

HB: She%u2019s 92.

PC: 92.

TW: Corine Cabaniss.

HB: She turned 92 in May, cause she and Daddy were the same age.

TW: And she worked for the Cohen%u2019s until they closed the store, and she%u2019s still working at Goodwill.

DW: Um-hmm. Wow.

[someone mumbles]

DW: Whew! I%u2019ll have to move here, cause a lot of people are in their nineties, or in the hundreds! [laughter] I%u2019ll bottle some of that up and take it with me!

TW: And she still drives!

HB: Yeah, she%u2019s still driving. Yeah, she%u2019s doing very well.

TW: And working %u2013 works some at Goodwill.

HB: And Miss Bridges is %u2013 she%u2019ll be 103 this month. July 19th. She%u2019s 103. Well, she has a memory like %u2013 ohhh.

DW: Oh my goodness.

TW: She%u2019s at Cleveland Pines nursing home.

HB: I think they%u2019ve interviewed her a couple of times over there.

DW: Um-hmm.

HB: And they%u2019ll probably do another interview when her birthday comes.

DW: That%u2019s coming right up.

HB: The 19th. What%u2019s today %u2013 the 14th?

TW: This weekend %u2013 Saturday.

HB: Yeah, they%u2019ll be over there interviewing her.

TW: Yeah, Corine Ca %u2013 I was thinking about that %u2013 I didn%u2019t see many black people in sales positions uptown. She was %u2013

HB: Yeah, because she worked for them %u2013 she started working for them as their maid, and then they just moved her, when they moved out of Shelby, they just put her in the store %u2013 gave her a job in the store. She worked for them for years.

TW: About what %u2013 fifty? Long time.

HB: Yeah, she still keeps in touch with them.

TW: She%u2019s been in retail over sixty years.

HB: Um-hmm. She%u2019s been there a long time.

DW: So, now %u2013 for blacks and jobs %u2013 have you seen that it changed a lot, in terms of what%u2019s available %u2013 over the past --?

HB: Yeah, seems like there%u2019s %u2013

TW: Primary jobs -- when I was coming up, everybody graduated and went to work in the mill, wasn%u2019t it, Pete, because this was a textile area. That was very %u2013 what%u2019s the word I%u2019m trying to think of?

DW: Industrial?

TW: Yeah %u2013 it was well %u2013 I mean, people didn%u2019t think a mill would ever close. I don%u2019t think they even conceived of that happening. They didn%u2019t conceive back in the fifties, sixties, seventies, that machines would take over manual power. But that was the people%u2019s attitude %u2013 I would think, at least half. The mentality %u2013 if they went to school, they went to either be nurses or teachers. Or it they wanted to go, they knew they had a job in the mill. And they worked %u2013 a lot of mill houses around here %u2013 this is a mill town.

DW: Were there a lot of %u2013 well, it sounds like your grandfather, and your father, and your great-grandfather were like entrepreneurs. Were there a lot of black entrepreneurs around? [several murmur %u201Chuh-uh%u201D] I guess maybe just like funeral businesses %u2013

TW: The Dockerys.

PC: Well, there was %u2013 yes, there were. Porter Freeman. That was whole little black-owned city over there. He had a cleaners, right? He had a restaurant.

HB: Yeah.

TW: Where?

HB: Up on Carolina Avenue.

PC: Yeah, up on Carolina Avenue. He had a cleaners, a restaurant, a cab stand.

[end of Disc 1]

HB: Barber shop. Beauty shop.

PC: A barber shop, a beauty shop. So, yeah, you have to do Carolina Avenue, and all the things that went on there. And you have to talk to Carl Dockery. Did somebody give you his name?

DW: Ummm.

TW: He%u2019s a funeral home %u2013 Enloe.

PC: You know him, don%u2019t you Miss Scott?

JS: Um-hmm.

PC: Oh, please talk to Carl.

TW: Paul Dockery and Enloe.

PC: Carl, and Paul, and I don%u2019t know %u2013 which Enloe is still alive? I know one of %u2018em.

TW: Kevin is the only living, and his mother.

PC: Is neither one of his uncles alive?

HB: No, no. He only had his daddy, was the only man.

PC: Is his mother still alive?

PC: Yeah. But she married into the Enloe family. But the Enloe was his daddy, and he had two sisters. And the sister %u2013 she still lives here. Her name%u2019s Elsie %u2013 Elsie Foster. She lives in the home up there on Buffalo Street.

PC: And one of the things we want you %u2013 you probably don%u2019t want to be remiss in is the first black doctor in Cleveland County.

HB: Dr. Ezell. The one that delivered me. He%u2019s the black doctor delivered me.

TW: He came to the house?

HB: Um-hmm.

TW: Wow. Dr. Ezell? I didn%u2019t know that. [pause]

HB: Then there was a Dr. Smith.

PC: Do you have a picture of Dr. Ezell?

DW: Oh I don%u2019t know %u2013 this is %u2013 um -- this picture. [laughs]

JS: I found that in a reporter%u2019s files, but it didn%u2019t have the name.

TW: In Shelby?

HB: We never had a black dentist, have we? We never had a black dentist.

PC: You know there was a black doctor who was killed, in Shelby.

HB: Dr. Singleton.

JS: Dr. Singleton?

DW: And he was killed?

HB: He died in an explosion.

PC: Murdered.

HB: We don%u2019t know he was murdered.

PC: I know.

HB: Oh, you do know? I%u2019ve ( )

TW: I remember people -- I remember hearing that.

PC: Ask Carl Dockery about that.

JS: Okay.

TW: His office was on Carolina Avenue.

PC: I don%u2019t know.

[several people talking at once]

JS: But -- just over the years %u2013 I%u2019d go to somebody%u2019s house and interview them for this one thing, and they%u2019d say %u201Cwell, you know, you used to have somebody that was killed back in the day, and da-da-da-da-da.%u201D And it was a black doctor, and some people say there was an explosion, an accident, but he was killed, not %u2013 but who would %u2013 where was it -- ?

HB: Well, did you not %u2013 where was that -- excuse me %u2013 some time back that the FBI was investigating the death of him --

JS: Yes, that%u2019s what it %u2013 yeah.

HB: -- the death of Dr. Singleton?

JS: Yes.

HB: Fifty years %u2013 something about it had become an investigation of an FBI file, that they were investigating his death. It was in the paper. [several murmuring] That they were investigating %u2013 it was 50 years ago.

TW: And Dr. Edwards was after that, wasn%u2019t he?

HB: He was here when Frankie was born.

TW: In the sixties.

HB: He was my doctor when Frankie was born %u2013 Dr. Edwards.

TW: Where%u2019d he come from?

HB: I don%u2019t know. He was %u2013 he came from in the mountains. But his wife was a teacher; she taught English.

DW: So %u2013 when childbirth happened in the house %u2013

HB: Yeah, I was born in the house %u2013 [laughs] I don%u2019t know what happened, but I was born at home. [laughter]

TW: What about Ann?

HB: Yeah, I guess she was born at home, too.

DW: When did %u2013 I guess at some point, blacks went to the hospital %u2013 around what time?

HB: Rayfield was born in the hospital. And Warren, [laughs] and Pete.

TW: All over here at Cleveland?

HB: Uh-huh.

TW: Probably Cleveland Memorial Hospital%u2019s %u201Cblack unit.%u201D

DW: Ohhh. [laughter]

HB: Now, Rayfield and Warren were born in the black %u2013 you know, it was segregated %u2013 they had the hospital for the blacks, but it was all in the same building. The blacks were in one area, and the whites were in another area.

TW: Oh, so Pete wasn%u2019t a part of that?

HB: No, no -- he was born %u2013 it was integrated then. Just Rayfield and Warren.

[pause]

JS: So tell us about the Negro fair.

HB: [laughs] I just know I went!

TW: Oh, Momma!