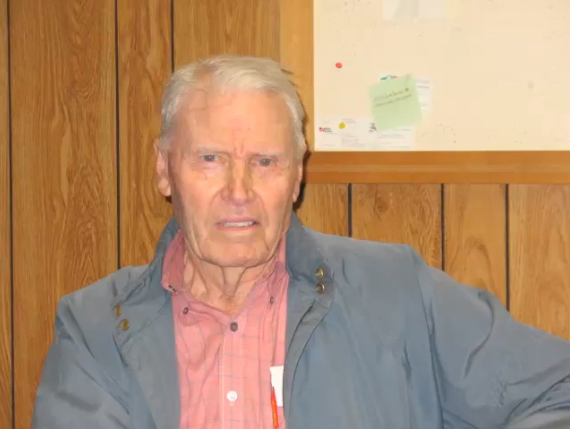

WILLIAM YANCEY ELLIS

Transcript

TRANSCRIPT %u2013 YANCEY ELLIS

[Compiled March 9th, 2010]

Interviewee: YANCEY ELLIS

Interviewers: Darlene Gravett, Katherine Brooks

Interview Date: February 15th, 2010

Location: Ellis Lumber Company Office, Shelby, North Carolina

Length: Approximately 53 minutes

DARLENE GRAVETT: The first thing we%u2019d like for you to do is to give us your full name and where you were born and when you were born.

YANCEY ELLIS: William Yancey Ellis, born July 30th, 1921, Cleveland County, seven miles down south of here, about a half a mile from ( ) River. The river that the city gets the water from over here, they call it %u201CFirst Broad.%u201D We always called it %u201CLittle Broad%u201D %u2018cause it runs into Big Broad just about a half-mile from where I live. I used to play in both rivers when I was a kid.

DG: Yeah, we want to hear about that, too. Let me say first of all that I%u2019m Darlene Gravett, and Katherine Brooks and I are interviewing Mr. Ellis. We are at the Ellis Lumber Company in Shelby and the date is February the fifteenth%u2026

YE: %u2026The fifteenth%u2026

DG: %u2026because Valentine%u2019s Day was yesterday, 2010. Okay, why do you mention that? Do you want to go ahead and talk about your connection to the Broad River? Are you part of the Ellis Ferry family?

YE: Well, yeah, a distant great-great uncle or something like that, or grandpa. I don%u2019t remember exactly how it is, but I%u2019m part of the original Ellis family. They settled--the land where I was raised was granted--I forgot the year, way back, from the King of England, when they first took up the land here. The land has been in the Ellises--and then other people got, at the time they went on, other people bought in on it. Not many Ellises left down there, but I%u2019m one of the few that still have some land down there. Of course, when I was down there, I was raised down there in an old house on top of a hill and no underpinning and no running water, no electricity, dirt roads, and we was kids. When we left there, we said, %u201CThe heck with that place,%u201D and didn%u2019t care if we ever went back.

KB: Oh, really? [Laughter]

YE: That%u2019s what we said, but as time went on, we got the road paved, and we got a water line, a county water line run down, electricity and telephone line. I have two kids that both of them live down there. They built houses down there, and they love it down there.

DG: Is that right?

YE: Back by themselves, yeah. Got plenty of room for their garden and all, yeah. They%u2019re different from what we were when we were down there.

KB: Now is this Ellis Ferry Road that you%u2019re talking about?

YE: Ellis Ferry Road, yes ma%u2019am. Yeah.

KB: Okay.

YE: I own the land, the old road bed down to where the ferry used to be, down to the ferry.

KB: Down to the river?

YE: Uh-huh.

KB: Okay. I used to go tubing down there some.

YE: You did?

KB: So I know that well.

YE: Yeah, I played in there. All us kids played in it as long as we lived down there. I stayed twenty years and left home. There%u2019s a lot of history to that Ellis Ferry down there. I don%u2019t know whether you want to know any of that or not.

KB: Sure I do.

YE: I used to hear my daddy talking about it. He said that they had--and his daddy was part of it too, part of the ferry folks. They had a raft; I think it was twelve feet. I got a picture I meant to bring. I have a picture of that ferry at the house, and it was twelve feet wide and eighteen feet long. What they would do, they would--they were down at the ferry--the ferry went across, it had a cable up here, and it went across and connected to Ellis Ferry Road on the other side and went into Gaffney. It%u2019s still the same way. Ellis Ferry Road goes into Gaffney, and into Shelby this way. So that is still the nearest way, I think two or three miles nearer down that way, to Gaffney, than where it is now %u2018cause it went down below Dravo Dam.

DG: Okay.

YE: They built a bridge down there and that--. The ferry washed away in 1916. My daddy was down there. He said the river got up as high as it ever been in his lifetime, and the ferry looked like it was gonna hold, but he%u2019d stick his finger up like that, and he said he saw this tree coming from down--the fork like that, and when that fork hit the cable that held the ferry, the ferry took off.

DG: Oh, no!

YE: But anyway, before that--getting back to the raft, they would get either cotton and tobacco or meat and tobacco, and load the ferry down. I mean, not the ferry, but the raft, and they would float down to Charleston. See, that river runs%u2026

KB: %u2026to Charleston?...

YE: %u2026into Charleston .

DG: Yeah.

YE: It runs%u2014I%u2019ll be right back. ( ) where it goes. [Interruption in recording while Mr. Ellis leaves the room]. That river starts at Hickory Nut Gorge, up above Chimney Rock. I%u2019ve been up there where it starts. It goes down by Duke Power at Cliffside, then down--. Where I was raised is where this little river here, Little Broad, we call it, they call it %u201CFirst Broad,%u201D runs into Big Broad. Then that runs into the Saluda River in Columbia, and this side, I%u2019ve seen the sign; I saw it a while back, the Saluda runs into Broad this side of Columbia. You go through Columbia and you go across the river, and it%u2019s the Congaree then. It%u2019s the Congaree. All right, the Congaree runs on down south into the Wateree. The Wateree runs into it, and then the Santee--the Santee runs into--getting bigger all the time, then the Cooper, the Cooper River. That%u2019s what they call it when it runs into Charleston. It%u2019s a big thing then.

DG: Yeah.

KB: A lot of fishing there.

DG: Yeah, and all the way out in the ocean.

YE: What they would do, they would, like I said, they%u2019d take the stuff down to Charleston and swap it for coffee and sugar. Bartering--they didn%u2019t any money much, and they%u2019d just swap it.

KB: So what were they taking? Cotton, did you say?

YE: Sometimes cotton, sometimes meat. Most of the time it was tobacco.

KB: Tobacco.

YE: I guess you didn%u2019t have tobacco in places over there. What they would do, they would float that down there. See, they didn%u2019t have any dams then. They%u2019d float down there. They had twelve men. Coming back up was the problem. They%u2019d have poplar poles about as long as this building, about that big, six men on each side and what they called %u201Cportage.%u201D Each one of them pushed; they%u2019d holler %u201CPush!%u201D Push a little bit at a time. It would take %u2018em, it would depend on the flow of the river how much, how fast you%u2019re going. But they said it takes a week to ten days to go down there. They%u2019d take two or three or four, five weeks to come back up.

DG: Yeah.

KB: Oh, wow!

DG: Coming upriver.

YE: Yeah, the higher the river got, the slower they got. Sometimes, if it got real high and they couldn%u2019t make any time, they%u2019d pull over and stop, camp a day or two and then start again, that kind of thing. It was a hard life, but they did it.

KB: Now, was it different twelve men or it was the same twelve men that--?

YE: The same twelve men. Yeah, they%u2019d float down and float back up, yeah.

DG: Wow! That was quite a bit.

YE: Then they%u2019d swap it for--people would come down there to the ferry. See, that was the ferry between Shelby and Gaffney. They%u2019d swap the stuff out.

DG: Yeah, yeah.

YE: If they had the money, they%u2019d sell it.

DG: So you have a picture of the Ellis Ferry?

YE: Yeah, yeah.

DG: I%u2019d love to see that. We%u2019re working on a Broad River Greenway Oral History. YE: Where I lived was about three or four miles below the Greenway.

DG: Yeah, okay.

YE: Maybe that%u2019s enough; I never measured it.

DG: Yeah, well, I saw that you were quoted in a supplement to the Shelby Star%u2026

YE: %u2026History ( )%u2026

DG: %u2026that was done in 1984%u2026

YE: %u2026Oh, yeah, yeah.

DG: I saw that you were quoted in there and that%u2019s why I was interested in hearing your connection to it.

KB: Now when did you start your business, your lumber company?

YE: I can tell you a little more about the ferry if you want to.

KB: Okay, go ahead.

YE: It%u2019s so comical, and I used to come out here and hear my daddy talk about it. He said that they had a circus; played in Gaffney, and they were going to play in Shelby next. You got to the ferry, when you crossed the ferry it was about dark, so they pulled up there to a neighbor%u2019s house about a half mile beyond my daddy%u2019s house, and they had two or three elephants. Farmers back then, you%u2019ve probably heard or seen a picture of an old

( ), a corn bin; had slats in it. They put the corn in a building about like this. So those elephants, they smelled that corn and they pushed the building over and ate corn all night. [Laughter] The next day my daddy wanted to shoot the elephants; they wouldn%u2019t let him. [Laughter]

DG: Oh, gosh, that%u2019s funny. Oh, dear.

YE: Now to go on to some of the other.

KB: Just about your--let%u2019s talk about your business as far as the lumber company. Did you start this or your grandfather?

YE: Yeah, but I had a background. Let%u2019s see, how do I want to start? One thing, I didn%u2019t have much sense back then. I was fifteen years old and in high school, went through eighth grade. When I started ninth grade, I kinda got tired of school, and my daddy came in one night. He run a sawmill, and he would--had an old truck. He would put the sawmill on the truck, and if a man wanted to build a barn and had some timber, had some trees, he%u2019d move it to his farm, set up and saw his lumber, and get his money and go down to somewhere else. He was a farmer. He farmed in the summertime, and the sawmill in wintertime and what they called %u201Claying-by%u201D time between crops. When crops got planted and before they got ready to harvest, he%u2019d have some time; he%u2019d run the sawmill then.

KB: Now this is your father?

YE: My father, yeah.

KB: And what was his name?

YE: Gordon Ellis.

KB: Garden?

YE: G-O-R-D-O-N, Gordon Ellis.

KB: Gordon.

YE: William Gordon Ellis. That%u2019s where I got part of my name.

DG: Um-hmm, William.

KB: Okay.

YE: But anyway, like I said, I was about to get tired of school. Daddy--I went in one night; Daddy came in and he said his main man at the sawmill quit. Said he didn%u2019t know; he had eight kids to feed and he didn%u2019t know how he was going to do, and this and that. I said, %u201CDaddy, I%u2019m tired of school anyway. I can make a hand at the sawmill.%u201D I had worked some anyway when I was a kid. I said, %u201CI can do his job.%u201D (Daddy said), %u201CAw, you can%u2019t do that.%u201D I said, %u201CWell I can try and learn.%u201D So the next morning, I didn%u2019t go to school; I went to the sawmill. Fifteen years old. Worked there for five years, and I made a hand. It was a job and I did it, handling lumber. So that kind of got me interested in lumber, so I got twenty years old and I said, %u201CWell, that%u2019s five years.%u201D I had saved up fifty-six dollars, and I left home with fifty-six dollars, and then my cousin carried me down to Union, South Carolina, and caught a train and went to Charleston and got a job in the shipyard down there.

DG: Oh, really?

YE: That%u2019s how I got down to Charleston.

KB: Oh, okay.

YE: So anyway, I worked there about a year and a half, a little better. Then the war came on.

KB: And what war was this?

YE: World War II.

KB: World War II.

YE: And I was in the draft. The shipyard picked out a bunch of us boys around twenty or twenty-one, twenty-two years old, put our name up on the board, a bulletin board, said we%u2019re going to have to go to the Army. I decided, well, and I went down to the draft board in Charleston the next day. I said, %u201CThey%u2019ve got my name on the board out there. About when will I need to go to the--have to go to the Army?%u201D He said, %u201CWell, be %u2018bout a couple of weeks.%u201D So I said, %u201CWell, I%u2019m going to go back and turn in my resignation [phone ringing] and resign from the job, and go home and spend a couple of weeks, then go to the Army. So I did that, and so then, after about two weeks I didn%u2019t hear anything, and I went another week and didn%u2019t hear anything. Then I got the newspaper; Daddy and Mama, they took the Star at the time. I picked up a newspaper, and it said the draft board was several weeks behind with their records, and they wasn%u2019t going to call anybody for at least a month.

KB: Huh-oh. [Laughter]

YE: So I said, %u201CDaddy, I%u2019ve been loafing here a couple of weeks. Now I need to go to work again. You need a man?%u201D (Daddy said), %u201CYeah,%u201D so I went back to work in the sawmill. [Laughter] Back in it again. I was twenty, twenty-two or three years old then. So then, I was cutting down a tree. I had to cut trees part of the time and sawing the rest of the time. Another man and me were cutting down a tree, a good-size tree, with a cross-cut. Didn%u2019t have chainsaws back then like that. We cut that tree down, and it went across the branch and hit another tree and knocked a limb off, and knocked that limb back and hit me in the top of the head. I had an old black leather cap, and I fell over. They thought I was dead.

DG: Oh!

YE: They got me up and got me to the hospital, and they sewed me up; I think ten stitches and I stayed in the hospital ten days.

KB: Ten--really? Did you have a concussion or was it worse than that?

YE: Yeah, a brain concussion, right.

KB: Oh, okay.

DG: Wow!

YE: So anyway, after I got a little better I got to where I could get around. I didn%u2019t have a headache too bad, so they called me to the Army. They called me down there. I went to Fort Bragg that time, and so they said, %u201CWell, we%u2019ll call you in a few weeks. We%u2019re not calling anybody right now. You%u2019ll be class 1-A. We%u2019ll let you know.%u201D But the war got over then, and I didn%u2019t have to go. I just ( ).

DG: Oh, so you never had to go. [Laughter]

KB: Oh, well, that%u2019s wonderful.

YE: I just come that close to%u2026

KB: %u2026That was a good deal.

DG: Right.

KB: So at that time, did you continue just to stay here and work?

YE: I got a job down in Wilmington. I went to Wilmington and got a job and worked down there about a year and a half. In the meantime, I got to going with a girl here in Shelby. Huh-oh. [Laughter]

KB: Now was this your wife?

YE: Yeah, so--. I married her. Had an apartment down there. We stayed down there a while and her mother got sick and she wanted to move back to Shelby. So, we moved back here. Then I got to wanting me a job; I needed a job. So I was uptown one day, and Daddy used to sell lumber to the Carl Thompson Lumber Company. It was--you folks don%u2019t remember it, but it was a yard right--you know where the Mexican restaurant is now, I believe. It%u2019s right across from the old market, Farmer%u2019s Market.

KB: Oh, yeah, yeah.

YE: Across the street.

DG: Mi Pueblito.

YE: It%u2019s a restaurant. At that time, that building where the restaurant is was the office and warehouse, part of the warehouse right then.

DG: Oh, really?

YE: Saw the boss man up there on the street one day; told him I was looking for a job. He said, %u201CWell, I don%u2019t know; I don%u2019t need nobody right now.%u201D He said, %u201CLet me have your phone number.%u201D He called me in two or three days and said, %u201CI%u2019ve got an opening. I%u2019d like to have you come up here and talk to me.%u201D I went up there and talked to him and he said, %u201CI%u2019d like to have you just come be a yard man. You count lumber, don%u2019t you?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D So, he hired me at twenty-five dollars a week. Fifty hours, fifty cents an hour. That was good money to me. I was well pleased with that.

KB: Back in those days.

YE: That was 1944.

DG: Yeah.

KB: 1944.

YE: Anyway, I worked there a year and a half, but in the meantime--like I say, I liked to work, liked that work, liked to work with lumber, and but I know it was several times a week, people would come in there with a pick-up load or a big truck load of lumber %u2018cause they wanted it dressed, that%u2019s smooth. Lumber--it was rough lumber. It%u2019s got splinters on it and it%u2019s different sizes. They can%u2019t cut it accurate enough to build a house. They used to, but it%u2019s much better to run it through a machine and dress it for a size and it works a lot better. So, he%u2019d--several times a week, he%u2019d turn down a dressing. He%u2019d say, %u201CTake it to somebody somewhere else.%u201D There were two other places in town that could do that. One day I was walking out across the yard there. I saw a big truck load of lumber pull up there and stop, and the boss man went out and talked to them and then he walked back in the shop. The truck pulled off. It just hit me; I thought if I had a little money. If I had a little machine. If I could just dress the lumber he%u2019s turning down, I believe I could make a living. I got to thinking and got scared. I never got nervous in my life. I said, %u201CI don%u2019t have any money much,%u201D and I said, %u201CHow can I start?%u201D No land, no money, I--I don%u2019t know. Went home that night and talked to my wife. I said, %u201CHow much money can we get together?%u201D We counted up, and we both had a little in the bank and a little at the house. We had twelve hundred dollars. I said, %u201CI know where I can get a machine and a motor for about that much money.%u201D I said, %u201CI can rent--may rent me an acre of land somewhere around here and set up my machine. If I can just dress the lumber Mr. Thompson%u2019s turning down, I believe I can make a living.%u201D She said, %u201CI believe it%u2019ll be all right.%u201D So I said, %u201CI%u2019ll be willing to put up what I%u2019ve got.%u201D So that day, I drove down to my daddy%u2019s house; he was living at that time. I told Daddy, I said, %u201CDaddy, I%u2019ve %u2018bout decided to quit my job. I%u2019m satisfied; I like to work for the man; never had words or trouble, an argument or nothing.%u201D I said, %u201CHe%u2019s turned down lumber several times a week, dressing.%u201D I said, %u201CI%u2019m thinking about putting what money I%u2019ve got--we%u2019ve got together and buy a little machine, rent me an acre of ground and put it up there and dress lumber for the public, see, and I believe I can make a living.%u201D So the next day, I told the boss man. He said, %u201COh, I don%u2019t want you to quit, don%u2019t want you to quit, no. I want you to stay on here.%u201D He said, %u201CYou%u2019re making twenty-five dollars a week?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D He said, %u201CI%u2019ll double your salary.%u201D

KB: Wow!

DG: Gosh!

YE: Double my salary for the same amount of hours. I thought oh, that makes it hard. Went back down there that next time; told Daddy what the man told me. He said, %u201COh, wait a minute.%u201D Said, %u201CYou might start on your own; you might make fifty dollars a week; might go broke.%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D He said, %u201CYou might be in debt and work half your life paying your debts back.%u201D No, he said, %u201CYou better keep that. Don%u2019t make a mistake like that.%u201D To this day, I don%u2019t know if I%u2019d have quit or not if Mama ( ). Went in there where Mama was cooking stuff on an old stove, wood stove. You know what a wood stove is.

DG: Oh, yeah.

YE: Told Mama, I said, %u201CMama, Rebeka and me have decided to put what money we%u2019ve got in a little machine to dress lumber, and I thought I could make a living. But, I told the boss man and he said he%u2019d double my salary, and I told Daddy what the boss man said. Daddy said %u201COh, don%u2019t make a mistake like that.%u201D I can%u2019t remember what happened yesterday. That was sixty-something years ago, sixty-five years ago. [Laughter] I said, %u201CMama, Daddy, he put a wet rag on my deal. I had done decided to quit my job and go to dressing lumber for the public, and Daddy said, %u201CNo, don%u2019t make a mistake like that.%u201D Mama said, %u201COh, you%u2019ll make it; go on,%u201D and to this day, I don%u2019t know, if she%u2019d agreed with Daddy, I don%u2019t know whether I%u2019d have started or not.

DG: How about that.

YE: That%u2019s a fact.

DG: She gave you the incentive, yeah.

YE: But anyway, we did. And this ( ), man that lived across the road there that rented the land. I told him I%u2019d like to rent an acre of ground out here. I said, %u201CWhen you harvest your crop this summer, this fall, you tell me how much I owe you for that acre of land of cotton that I destroy, and I%u2019ll pay you.%u201D He said, %u201CGo ahead.%u201D So that%u2019s how I started. I went out there with a little machine. We had ( ). We had twelve hundred dollars; we spent eleven-hundred-and-thirty-five dollars. We had sixty-five dollars between us, and that sign out there, %u201946.

KB: Wow, and this right here is where you started?

YE: Yeah, right here.

KB: Right here.

YE: Later on, I bought ten acres here and then I bought two acres more up there, and then bought some more back here. I just kept on expanding.

KB: So how many acres do you have now?

YE: I have twelve here, and I have about four hundred down--acres down at the river where I was raised.

KB: Oh, so you own that land down there at Ellis Ferry now?

YE: Oh, yeah.

KB: Four hundred acres?

YE: Yeah.

KB: Do you use that to cut your lumber and to bring it here?

YE: Some, some, but most of it is just to let it grow into more timber. And my kids--I deeded off some of it to my kids. They wanted to--. It started with one, and another one wanted it. Now another has got some land down there, but she hasn%u2019t built yet. I divided up some of that between the kids.

DG: How many children do you have?

YE: I have two girls and two boys. The two boys are here.

DG: Yeah, the two boys are here with the business, aren%u2019t they?

YE: Yeah, that%u2019s right, yeah. I%u2019ll gradually turn it over to them. So that%u2019s about the story of the way I got started here.

KB: What was your daddy%u2019s name?

YE: William Gordon Ellis.

KB: William Gordon, okay, and you already told me that. And your wife%u2019s name?

YE: Rebeka, R-E-B-E-K-A is Rebeka. My mother was named Gertha Ellis.

DG: How do you figure that you%u2019ve been so successful with this business, with Home Depot and Lowe%u2019s and all those big stores coming in?

YE: Yeah, that%u2019s a good question. I fought them for years, and I just got to where I couldn%u2019t make any money. I%u2019ve worked this thing all the year, and I%u2019d have less money in the bank at the end of the year than I had at the start.

DG: Oh.

YE: So I gradually, over the years, fifteen years or so ago, I had machinery to handle big timbers, like that big stuff, instead of--. Home Depot, they have two-by-fours and two-by-sixes, little stuff; that%u2019s why I couldn%u2019t make any money, from fighting them.

So I got in the log home business. You%u2019ve seen log homes?

KB: Right.

YE: Started out right easy. The more I went into that, my bank account started building up. I found out two things. I found out that--I never thought of--I didn%u2019t know there was as much demand for that stuff as there is. Not around here, there%u2019s some built around here, but most of it is around the edge of the mountains, lakes and all. But I found there%u2019s a big demand for it, and no competition within a hundred miles of here.

KB: Well, that%u2019s great. Still, to this day?

YE: To this day. Oh, yeah. Well, I couldn%u2019t--to this day, I couldn%u2019t fight with Lowe%u2019s and Home Depot; I couldn%u2019t make it, no.

KB: So, you market more the log home, the larger--?

YE: Yeah, yeah. We still do some hardwood furnishing business. A lot of the big hardwood furniture companies went out of business, Drexel and%u2026

KB: %u2026Right.

YE: A lot of them went out of business, but there%u2019s some small outfits out in Hickory and Conover, up in there. We still furnish some lumber for them to make furniture. They are small outfits and they can make special stuff. One place that--one of our best customers makes little, all little stuff, from coffee tables to bedside table lamps, little ol%u2019 stuff like that. He ships it all--she said he ships a lot into Florida and all over the country. He%u2019s still doing pretty good. We do some of that. No competition in that, you see, and that%u2019s a pretty good sideline for us.

DG: Great. You found your niche. You found a niche.

YE: That%u2019s what it is. It%u2019s a niche. That%u2019s what it took, yeah.

DG: Yeah, yeah.

KB: And you said that you were living in Wilmington?

YE: Wilmington, when I moved back to Shelby, yeah, and got me a job.

KB: Okay, and got your job here. Do you have children, still, all your children here, still live in Cleveland County?

YE: Karen, one of my daughters, lives down there on the river, like I said. They built a house down there, and Scott, there%u2019s two of them down there. Then Tim, one you saw in there, lives right down this side of James Love School. We own that land, and we owned the land--I owned the land for the school.

DG: Really?

YE: Yeah, back then. Yeah, I sure did. We got to deed him off three acres, and he%u2019s got a pretty nice house right down there. Then Becky, my daughter, talked to her a while ago, I said, %u201CHuntsville, Alabama is famous.%u201D

DG: Yes, it is, unfortunately.

YE: Famous town. That%u2019s where they live. That%u2019s where they live, Huntsville, Alabama.

DG: That%u2019s where the professor killed, shot and killed--.

KB: Oh, okay.

YE: Where all that shooting went on. Yeah, sure did, not too far from where they live.

DG: It%u2019s scary.

KB: Well, let me ask you this. Do you play a musical instrument? Or did you ever?

YE: Oh, that%u2019s a long story there. I better not go into that. [Laughter]

My daddy was a good fiddle player, and he could play a guitar pretty good. He had a little band. Leabron Rogers was one of his friends about his age.

DG: Who was that? What was his name?

YE: Leabron Rogers.

KB: Leabron.

DG: Leabron, okay.

YE: He played a banjo, and Miller Ellis, Daddy%u2019s second or third cousin, played a ( ). He had a little three-piece band, three-man band. They%u2019d get together at either one of them%u2019s house and practice and play. Then several times a year in the summertime, some of the neighbors might want to have a dance in a house, and they%u2019d go out and play for a dance in the house back then. So I got to try to play Daddy%u2019s guitar. Well, it was too big for me. You might not want to go into all of this. It%u2019ll take a little bit to tell this about the guitar story.

DG: Well, it%u2019s okay; we%u2019re going to see if your%u2026

YE: %u2026You can edit out some of it there. You can edit out what you want to.

DG: Well, yeah, yeah.

YE: Yeah, that%u2019s the thing to do.

KB: You just keep going.

YE: Leabron Rogers was a good banjo player, and his son is Ernest Rogers. You see Rogers on the TV, Rogers Motors.

KB: Right.

YE: That%u2019s a...

KB: %u2026The Rogers%u2026

YE: %u2026Rogers Automotive.

KB: Yeah.

DG: Yeah, we see them all the time. [Laughter] A lot.

YE: I knew him. He had, let%u2019s see, he had five or six boys and one girl. I knew the whole family, and they were tenant farmers back then. Daddy owned our land. He owed some money on it, but the Rogers were tenant farmers. You know what that is, they%u2026

KB: %u2026Tenant, yeah.

YE: The landowner furnished their land and the fertilizer and the seed, and they planted and then harvested and split the money. That%u2019s how you did. Anyway, I got to wanting to try to play a guitar, and I%u2019d get that ol%u2019 big thing up and couldn%u2019t hardly reach it and I kept--. And Mama saw in a Sears Roebuck catalog--get a smaller guitar for five dollars. It took me a while to get Daddy talked into spending five dollars on a guitar [laughter] for me to play with. ( ). I was proud of that thing. I played that thing. I%u2019d play it and when I got grown I%u2019d still try to play it. Mr. Leabron Rogers, he got to wanting to play a guitar like that and if you noticed--. I don%u2019t know whether you ever noticed people playing guitar, most of %u2018em fram it like this, have a flat pick and they fram it like that.

KB: Strum.

YE: Daddy picked like this; you call that %u201Cthumb picking.%u201D

KB: Like a banjo picker.

YE: Like a banjo, yeah, and Mr. Leabron was a good banjo picker, and he thought he could learn to play a guitar like Daddy. That tenant farmer, back in %u2018bout %u201931 or %u201932, went to a music store and paid fifty dollars for a guitar, to try to learn to play like Daddy. He kept it a year or so, and he was down at the house one day and I said, %u201CMr. Leabron, how much--I haven%u2019t seen you picking your guitar lately. Still got it?%u201D %u201COh, yeah.%u201D I said, %u201CDo you still pick it?%u201D He said, %u201CNo, I decided I can%u2019t pick like your daddy, so I just quit.%u201D I said, %u201CDo you want to sell it?%u201D He said, %u201CYeah.%u201D He said, %u201CYou got any money?%u201D I said, %u201CNo.%u201D [Laughter] I said, %u201CI got a bicycle.%u201D I had an old bicycle. I had fixed it up and painted it. I%u2019d rather give up my right arm than that bicycle, but I said, %u201CI%u2019ll trade you the bicycle.%u201D He said, %u201CGo get it.%u201D I went and got it. He said, %u201COne of my boys is wanting a bicycle. I%u2019ll trade you the guitar for the bicycle.%u201D

DG: Wow.

KB: Wasn%u2019t that neat?

YE: So he went and got the guitar and I let my bicycle go. I hated to, but I got to--on that thing, I was about grown then. I was fifteen or sixteen years old. I really got--I said, %u201CI want to try to play like Daddy.%u201D Then Daddy got us an old battery-powered radio in 1936, and then we could turn on WLW station, WLW Cincinnati, early at six-thirty in the morning before Daddy went to work. They had Merle Travis on there. Now he%u2019s one of the best guitar pickers there ever was. He could beat Daddy. I said, %u201CDaddy, there%u2019s a man I want to imitate. I want to get like him. I want to beat you.%u201D [Laughter] I really went to bearing down on the guitar. I messed with that thing %u2018til I was twenty years old. That gets back to when I left home. I got to thinking about the thing. I said now, %u201CI wanted to get as good Merle Travis. I want to beat Daddy. I%u2019m not good as Daddy. I%u2019ve got to make a living somehow, and I can%u2019t do what I want to do on a guitar and make a living.%u201D I%u2019m laying it out, pushing it under my bed, then I left home, like I said, with fifty-six dollars. And I give up on my guitar. Time goes on; it goes way on and goes, keeps on going. I started here--then one day--now, Daddy had a colored fellow that worked at the sawmill. I was in Charleston at that time. Had an old motorcycle and rode in home there one weekend, and this boy said, %u201CMr. Ellis, you still got your guitar?%u201D He couldn%u2019t say %u201Cguitar.%u201D He said %u201Cgui-tah.%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D He said, %u201CDo you want to sell it?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D I said, %u201CI%u2019m not going to mess with it any more. I don%u2019t have time to mess with it. I%u2019ve got to make a living.%u201D He said, %u201CGo get it.%u201D He looked at it. He said, %u201CWhat do you want for it?%u201D I said, %u201CTwenty-five dollars.%u201D He said, %u201CCan I pay you five dollars a week?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah, if you give me five dollars,%u201D and I didn%u2019t have the guitar and he paid me twenty-five dollars for it.

KB: He was an honest man.

YE: Yeah. Time went on. Several years went on. He quit the sawmill, quit Daddy%u2019s sawmill, went to working for somebody on a farm. He didn%u2019t like that. He walked by here one day, and I was out there working. I had a couple of men, two or three men hired then. He said, %u201CYou need a man?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah, this is hard work. You know what hard work is, about like a sawmill.%u201D He said, %u201CYeah, I%u2019d like to have a job.%u201D I think I paid him at that time, fifty cents an hour. That%u2019s what I was making before I started.

DG: Yeah, right.

YE: Anyway, after several years, one Christmas, Rebeka, my wife, found out that he still had my guitar. So she went down and bought it from him.

KB: Oh, how sweet.

YE: He lived down below the school. Went and bought the old guitar%u2026

DG: %u2026Is that right?...

YE: %u2026and I still have it to this day.

KB: You still have it to this day? Oh!

YE: The Rogers man, it%u2019s his son runs it now. Ernest Rogers, the man that--still owns the building up there. But he was out here getting lumber. Oh, it%u2019s been a year or so ago and he said, %u201CBy the way, you still got my daddy%u2019s old guitar?%u201D I said, %u201CYeah.%u201D He said, %u201CWhat do you want for it?%u201D I said, %u201COh, I don%u2019t want to sell it.%u201D He said, %u201CI%u2019d like to have it. Make me a price on it.%u201D I said, %u201CNo, that%u2019s the only thing I%u2019ve got I had when I was a kid, and I don%u2019t want to sell it.%u201D

KB: Isn%u2019t that something?

YE: That%u2019s the old guitar.

DG: I don%u2019t know if you were going to ask this or not, and you maybe were, but did you or your dad know Earl Scruggs?

YE: Oh, that%u2019s another story. [Laughter]

KB: I was going to lead into that, if you ever played with Earl Scruggs or Don Gibson?

YE: Yeah. I didn%u2019t know Don. Knew Earl well. I%u2019d seen Don, but never really talked to him. Yeah, Earl--Daddy had a sawmill on the Gardner-Webb farm. I forgot who owned it. Some Gardner--some Gardner, I believe, owned the Gardner-Webb farm or part of it. Anyway, they wanted some lumber sawed, and Daddy moved the sawmill down there and was sawing lumber for them. So he came in one night, and that was before I--yeah, I was still in school then. That was before I quit school. Anyway, he come in just one night and he said, %u201CYou know, they had a little circus over there at Boiling Springs. They had a little boy up there on the stage picking a banjo.%u201D He said he was a good banjo picker and said he was twelve years old. He said, %u201CI found out he was Junie Scruggs%u2019 brother.%u201D Junie Scruggs was a pretty good banjo picker. That was Earl%u2019s older brother. Daddy played some with him. Said he found out it was Earl Scruggs and said, %u201CThat boy%u2019s going to beat Junie before long. That boy%u2019s going somewhere on the banjo.%u201D

DG: Oh, really?

YE: First time I heard of Earl Scruggs he was twelve years old right then.

KB: Now, at that time, how old were you?

YE: I think I%u2019m a year older than him. I was about thirteen or something like that.

KB: Okay, so it%u2019s about the same.

YE: We%u2019re close to the same age. Yeah, that%u2019s right. That%u2019s right. Oh, yeah, and I kept up with Earl. We went to--one was friends and one was sons--he was going up to Nashville, and we--. Let%u2019s see, Earl had a brother working at Gardner-Webb named Horace; he went with us. We stopped at Earl%u2019s house, went through his house, and his brother spent the night with him. We went on to a hotel and spent the night. We enjoyed that, and then we went again. Earl started--that was in the sixties, I think. Earl started home one weekend to visit his mother; she was living here, and some ( ) fellow pulled out in front of him and wrecked him and almost killed him.

DG: Yeah, I heard about that.

YE: We were up there in Nashville again at that time. We went to the hospital and talked to him.

DG: Wow.

YE: He was in the hospital. I said, %u201CEarl, you haven%u2019t got your banjo ( ). You don%u2019t play it, do you?%u201D He said, %u201COh, these doctors around here, they hand it to me and want me to play the banjo.%u201D

KB: So at that time, I guess he was quite popular.

YE: Yeah, that%u2019s right, that%u2019s right.

DG: Oh, gosh.

YE: Oh, he%u2019s been at my house. He pulled up there one time, a big ol%u2019 long limousine, %u201CMartha White Flour%u201D all over the side of it. [Laughter]

KB: Oh, interesting!

DG: Yeah, that is very interesting. Did you go to see the show when he was here?

YE: No, I was out of town. I wouldn%u2019t have missed it if I had been here.

DG: It was packed. It was full.

YE: They said it was, yeah.

DG: He did a good job, yeah, of course.

KB: So you still have the guitar? I%u2019d love to take a picture of it with you holding it--the guitar that you still have. I think that%u2019s neat. And you said that was Mr.--that was Ernest Rogers?

YE: Ernest Rogers%u2019 father%u2026

KB: %u2026Father%u2026

YE: %u2026that I got the guitar from, yeah.

KB: And that was Leabron.

YE: Leabron Rogers, L-E-A-B-R-O-N, Leabron Rogers.

KB: As far as Cleveland County and how you look at it now and then and all, what do you think is--like what stands out to you most about the changes?

YE: Oh, a lot of things. The biggest thing that helped this part of the country, county, was paved roads. Back when we had a T-Model, had a T-Model car--you know where Wendy%u2019s is right now?

KB: Uh-huh.

YE: That%u2019s where the pavement stopped. Belmont Mill was across the street.

DG: Is that right?

YE: Yeah, and the old car, when it would go off the pavement and bounce down on the dirt, boom-boom-boom! That scared me. I thought the old car was going to tear up. [Laughter] But, we would--Daddy would take us to town, when the weather was good, take us to town sometimes on Saturday. If we had saved up a nickel, we%u2019d get us a nickel cone of ice cream. Then he%u2019d stop at Evie Crane%u2019s store down here, a store building.

KB: What was it called?

YE: Evie Crane. E-V-I-E, Evie Crane%u2019s store.

KB: Evie Crane?

YE: It%u2019s a variety shop now.

DG: E-B-I-E?

YE: E-V-I-E, Evie. Evie Crane, yeah.

DG: E-V-I-E. Oh, okay.

YE: He would sell coffee and sugar a little cheaper than they would in town, and Daddy and Mama, they%u2019d stop there and buy their sugar and coffee. Later on, before I left home, I told Mama, I said, %u201CMama, I%u2019m going to have a job sometime. I%u2019d like to work for myself.%u201D I said, %u201CI wonder if I could save up enough money and get enough money saved up to buy an acre of land up there on 18 (highway) and start me a little store like Evie Crane. I believe I could make a living doing that.%u201D She said, %u201CThat might do.%u201D But time went on, and Evie died. He didn%u2019t have any kids and the bank was settling up his stuff, so I bought the Evie Crane house and the store building, so I own it myself.

DG: Oh.

KB: So did you run the store for a while?

YE: No, no, no, no. They had sold it out. There wasn%u2019t anything in it. I just bought it and I rent it. I rent the house and I rent the store building, that variety store down there.

KB: You sound like you were a very ambitious person at a young age.

YE: Oh, I don%u2019t know about that.

KB: Let%u2019s see what else I have here. If you have anything, go ahead.

DG: What was it like growing up in Cleveland County?

YE: It was hard. It was hard. Like I said, we got dirt roads. An old T-Model car, Daddy used to--he kept a car most of the time. But, in weather like this, the ruts would bow down %u2018til the axle would be dragging, and if you met a car, one of them would have to stop %u2018til you got to somebody%u2019s driveway and back in that driveway and let this man through.

DG: Oh, yeah.

YE: Several people down below us there had buggies, horse and buggies. I remember that, I sure do. Daddy had a T-Model car; he was a little bit [laughter] more well-off than the other--. He didn%u2019t have anything.

DG: Now where did you go to school?

YE: Broad River School was%u2026

DG: %u2026Broad River School.

YE: Yeah, they called it Broad River School.

KB: Now is the building still there or not?

YE: No, no, they tore it down. I was in the%u2014I finished the third grade at Broad River School. It was a wood building, two rooms; first, second and third grade and the fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh in the other room. It had a partition between %u2018em. After I finished the third grade, they put a bus on the road, and it%u2019s still dirt road and hauled, carried us to Earl School. I went there the fifth, sixth and seventh grade.

KB: And where was that?

YE: Earl School. Earl, the town of Earl.

KB: Oh, okay, Earl.

YE: The school is still there, but it--made %u2018em an annex for the church out of it. Consolidated the school with Patterson, I believe it was. Anyway, I went to Number Three School, which is about a mile on this side of Earl, Number Three Township School. It%u2019s a pretty good size school. I went there the eighth grade and a few months in the ninth, and that%u2019s when I ( ). I tell people if I hadn%u2019t been a fool and quit school in ninth grade, if I%u2019d gone--. Daddy told me, %u201CGo on to college. You could make a surveyor or a lawyer and make a lot more money than you could working a sawmill or something like that.%u201D So I tell %u2018em when ( ) and got a good education, I might have amounted to something. [Laughter]

DG: But you know, so many men your age back in that generation, and women, had to quit school, sometimes to help their families.

YE: I did. I saw Daddy--that%u2019s the first time I%u2019d ever seen him cry in his life. He came in crying and said, %u201CHow am I going to feed eight kids?%u201D and the main man quit, and I decided--I said, %u201CWell, heck, I can fill in now. I can help him raise the family,%u201D and I did.

KB: Now, your eight, the eight children, are they still around here? Did they go on to--?

YE: No, half of them are gone. Four of them are gone.

KB: Did they go on to the lumber company or anything like that?

YE: No, no, none of them.

KB: Did they start their own businesses?

YE: Well, I had a sister. I have a sister that%u2019s still living. She%u2019s seventy-two years old. She married a--that%u2019s a story in itself there [laughter]. I tried to get the Charlotte Observer to print that story. It would be worth something if they could print it.

DG: Who is--who is she? Yeah, go ahead and tell us. Who is she? What%u2019s her name?

YE: My sister%u2019s name is Ruth. Ruth Ellis Arrant. His name is Larry Arrant from Indian Trail.

KB: What%u2019s the last name?

YE: A-R-R-A-N-T, Arrant. Larry Arrant. She married him and she worked at the telephone office, Bell Telephone at that time, in Charlotte. They got together and got married. He was a machinist working at a machine shop, but he was going from Charlotte--they lived in Charlotte, outside of Charlotte, going to Gaston Tech, Gaston--whatever that college is...

DG: %u2026Gaston College%u2026

YE: %u2026going there to take training to be a better machinist and hoping to make more money. Up at the house one weekend, Christmas, he had a Chevrolet car, but that time, he had a Volkswagen. It was a used car--Volkswagen. He was bragging on it. He liked it so much better and it got so much more on gas mileage and all that stuff. Well, the next week, he was going from Charlotte to Gastonia College, running low on gas and went and got his gas and took off. It was raining. Took off down this way, and passed this Greyhound bus and before he got to the Catawba River--you know where the Catawba River is, on this side of Charlotte. The bus driver said he passed him and the wind was blowing, and said the Volkswagen did this, then it straightened up and it did this again in the median, like that, turned over and went over an Oldsmobile, a man and his wife in an Oldsmobile coming this way. It rolled over the top of them.

KB: Oh, my gosh!

YE: His left arm--I believe it went in the car. Lost his left arm. He rolled on down a hundred yards, they said, on that concrete. I went to see him in the hospital and all I could see was his nose and his eyes. Everything was plastered from here to--.

KB: Oh, no!

DG: How terrible!

YE: Yeah, he was ruined. Oh, he was crying and said, %u201CYank, I can%u2019t make a--I can%u2019t run a lathe; I can%u2019t make a living. I don%u2019t know what in the world I%u2019m going to do, and I wish I could die. I%u2019d just like to die and get rid of everything. I said, %u201CNo, Larry, you%u2019ll make it. Ruth makes a good salary there at Bell Telephone.%u201D She was a supervisor. I said, %u201CYou%u2019ll make it.%u201D He got out of that. I hadn%u2019t done anything to what he%u2019s done. He got him a lathe. You know, a lathe making--one of the mills there wanted some little things about like a silver dollar with a hole in %u2018em. He got to making them by the dozens and then by the hundreds. Another mill got to buying some of %u2018em. Started in his daddy%u2019s chicken house, got him another lathe and hired a man to run it making more. He got started--he was ( ) twelve acres of land down there close to where he was living, and took a house, took a house and made part of that house into his shop and part of it his office. He started building, and my building down there, I could put mine in his and walk all the way around it.

DG: Oh, no, really?

YE: He had done wonders. He had done wonders.

KB: That%u2019s great. What was the name of his company?

YE: Northwest Tool and Die.

KB: Northwest Tool and Die.

YE: The Charlotte Observer was the one that was interested in it, but they were laying off some help down there and they were in turmoil. I told them that would be a good story to write. But, oh, he%u2019s had all kind of trouble. He%u2019s had a dozen operations or more. They say if they can cut your arm off and sew it back, and sew the nerves up and all, you don%u2019t have too much trouble. They say if you jerk it off, it pulls nerves off all back in here.

KB: It rips out.

YE: He%u2019s had operation after operation, tying up nerves back there. Ruth got to noticing several years ago when he was asleep, it just cut his breath off. His tongue cut his breath off, and just may have set there a minute, laid there a minute without his breath. Carried him to the doctor and they said he had a deformity when he was born. Some way his tongue, when he lays down and relaxes, his tongue covers his windpipe.

DG: I%u2019ve never heard of that before.

YE: I never had. I forgot what they call it. I know they couldn%u2019t find a doctor in this part of the country who would operate on him. Los Angeles, California, had a doctor out there that operated. He went out there, and in two or three weeks he got that done. Well, like I said, he had a heart transplant, all kind of stuff.

DG: Good heavens!

KB: Wow! So he survived a lot.

YE: Yeah, he%u2019s had all kind of trouble, yeah.

DG: But he%u2019s still living?

YE: Oh, yeah, yeah, still is.

KB: Does he still have a company? Does he--?

YE: Oh, he%u2019s worth several million. He%u2019s bought one, two machines that cost $680,000 apiece. He%u2019s working for the government. He%u2019s sending stuff into Iraq right now.

KB: So he%u2019s still in Cleveland County?

YE: No, he%u2019s in%u2026

DG: %u2026In Gastonia%u2026

YE: %u2026Mecklenburg, I think. Indian Trail, that%u2019s where he%u2019s at.

KB: Indian Trail.

DG: Oh, okay.

YE: I thought the Charlotte Observer might want to write it up, but they didn%u2019t--haven%u2019t done anything yet.

KB: That%u2019s very interesting.

DG: So where were you in the line of children? Which one were you?

YE: I%u2019m the oldest.

DG: You%u2019re the oldest. Oh, okay.

YE: Yeah, yeah. You know, Ruth is the youngest.

DG: Yeah, well, you said seventy-two, and so that--and you%u2019re eighty-eight now?

YE: Eighty-eight. Right.

DG: And--go ahead.

KB: Go ahead. Did you start to say--?

YE: That%u2019s about it for a minute. Y%u2019all may edit out a lot of this junk that I put in there if you want. Another thing, I went to Charleston last month. I got to thinking about it. This water right over here and the water that comes out of Hickory Nut Gorge, Broad River, like I said, you can track it down and it goes into Charleston. I drink that water down there and I said, %u201CYou know, I%u2019m probably drinking some of the Broad River water down there at Charleston.%u201D

KB: That%u2019s right.

YE: That%u2019s where they get the water, out of the Cooper River.

DG: You probably are. That%u2019s exactly right.

KB: I was going to ask, do any of your grandchildren, do you think that they%u2019re going to carry on your business?

YE: Scott has a son that%u2019s interested in it. Now he%u2019s already said--three of my kids went through college. Tim had--got Master%u2019s degrees, but Scott, when he got through high school, I said to him, %u201CYou want to go to college, don%u2019t you? and he said, %u201CNo.%u201D I said, %u201CBoy, you ought to go to college and get you a degree. You might want to do something else besides working in lumber sometime.%u201D He said, %u201CNo, I%u2019ve been working here when I wasn%u2019t in school. I don%u2019t want to go to college.%u201D So I said, %u201CWell, it%u2019s up to you.%u201D And he%u2019s got a son the same way. He%u2019s in the eighth or ninth, eighth grade, I think, now, and he said when he gets through high school, he can work here.

KB: Well, that%u2019s good.

YE: If they have a holiday, he%u2019s out there working.

DG: Oh.

KB: That%u2019s great.

YE: Yeah.

DG: Yeah, yeah, it is.

KB: He must have his grandfather%u2019s ambition [laughter] and drive.

YE: I don%u2019t know about that.

KB: Where are some of the companies--? You said something about the log homes that you sell. Where are--what areas are some of the companies that you sell to?

YE: Two of the biggest customers are Green River Log Homes in Campobello, South Carolina. And right across I-26 from them is Blue Ridge Log Homes. They are big; they ship log homes--what they do, they build them over there in sections like these house trailers. They build %u2018em with one side and roof on there and put black paper on the other side, take %u2018em to the job and take a crane and put %u2018em together. They can build a house every day like that. They ship those things--they%u2019d been, up %u2018til last, just in the last year, they%u2019ve started crossing the Mississippi River. Got the ( ) for this--from the Mississippi River back this way, and all them mountains, lakes and all, they%u2019re sending those things everywhere. It%u2019s good business for us.

KB: I bet that makes you proud to think that came from right here in Cleveland County and to be able to spread out like that. That%u2019s amazing.

YE: We see some of our stuff up in the mountains. We sell some to contractors up around Marion and Spruce Pine, up in there to build log homes. We sell %u2018em ( ).

DG: Is that right?

YE: Yeah.

DG: Wow. I was just going to ask if you have any hobbies? Do you have time to have hobbies?

YE: [Laughter]

DG: You gave up the guitar. Did you pick up anything else?

YE: No, no.

DG: Have you--do you golf or fish or--?

YE: Some of these boys, people that worked here years ago, they got to playing before they had a golf course around here. They got to playing golf at Gastonia. Oh, we had a good time. They got a good course. You%u2019d go down there and you%u2019d like golf. One time I said, %u201CBoy, I don%u2019t believe I like it.%u201D %u201COh, you have to go again. One more time and you%u2019ll get to liking it.%u201D I went two times. That was%u2026

DG: %u2026You didn%u2019t like it?...

YE: %u2026enough for me.

KB: I%u2019ve played once and I couldn%u2019t%u2026

YE: %u2026I beat you.

KB: Took fifteen times to get in the hole.

YE: I%u2019ve got two.

KB: That%u2019s a tough game.

YE: Knock a ball and run and pick it up and knock it again. I couldn%u2019t see that.

KB: That%u2019s right.

DG: So your life has been work?

YE: Yeah.

DG: And family.

YE: Yeah, that%u2019s right. Yeah, and family. That%u2019s right, yeah.

DG: Work and family, yeah. Is your wife still alive?

YE: No, she died three years ago. First of next month will be three years.

DG: Three years, okay.

YE: But she--we made, I guess you would call it a good team. Not trying to brag, but she ran a house and raised the kids more than I did. She carried them to their recitals and plays and whatever. She never let one kid ride a bus one time. She always carried them. I furnished her a car and she carried the kids to school and all, and I ran the business. But I was so determined when I started. I said, %u201CNow I%u2019m in good health. It was work that caused me to make my daddy out wrong. I hope I live long enough to see him wrong. I want to make him out wrong, at least try to get me enough to quit my job.%u201D So I first started, I%u2019d work %u2018til it got dark. Then after I got to buying and selling some lumber and needed more help, why I got to working--I got lights. I had to run with a gasoline engine to start with, couldn%u2019t get power.

DG: Oh, really?

YE: It was two years, yeah. Duke Power said it was ( ) in %u201946. They said wire is short and all this and that. They said, %u201CWe%u2019ll get you power in about two years.%u201D After we got power, then we got to working after dark, and for years, ten or more, my regular day was Rebeka would get up at four o%u2019clock and fix breakfast and have me over here at five o%u2019clock. And I worked %u2018til ten o%u2019clock at night.

KB: Wow.

YE: And that was my day for years and years. Some of the neighbors over there--see me at church? Why do you run that old machine at night? I can%u2019t sleep. [Laughter] I said, %u201CI%u2019m trying to make a living.%u201D [Laughter]

DG: Oh, dear.

KB: Oh, that%u2019s funny.

YE: I%u2019ll probably think of something else tonight I left off, but that%u2019s all I think of right now.

DG: Well, do you have any other questions?

KB: I was going to ask you what you think--how you see Cleveland County, maybe in the next ten years?

DG: Good question.

KB: As far as development.

YE: I%u2019ll tell you what. You got a hard question there now. This fellow, Glen Beck on TV scares me to death. He says he%u2019s got us in debt so much that I don%u2019t know what%u2019s going to happen there. I%u2019m just hoping that we can get somebody in there to straighten the thing out and get us more near out of debt, and quit going into debt so deep, and things will be all right.

KB: Traditions? Any type of special traditions that you recall doing or being a part of when you were growing up, besides holiday traditions, but something that you kind of did on a routine basis? Besides work, if you had time. [Laughter]

YE: I didn%u2019t have much time. I%u2019d take my kids on the weekend--I worked there the thirty-two years and I%u2019d give these boys a week off with pay every summer, but I worked thirty-two years and never took a week off. Sometimes it would be fine, but once in a while, if I wanted to take the kids to the mountains, I may take off Thursday afternoon, take off Friday and come back Sunday and be ready to go to work Monday morning.

KB: And what mountains did you go to when you went?

YE: My dad and father-in-law and mother-in-law had a little place up near Burnsville.

KB: Burnsville.

YE: Burnsville, above Marion. We%u2019d go up there and spend the weekend.

KB: Well, that is great. Now this is just really for myself, but as far as lumber company and you said finishing lumber company and then the sawmill. What%u2019s the difference in those?

YE: A sawmill, all they can do is saw rough lumber. They take a log%u2026

KB: %u2026And they have one of those big, huge saws?

YE: Yeah, right, and they make lumber. But carpenters now don%u2019t like to use rough lumber. It%u2019s--to carry it and all, it%u2019s such a big and heavy thing, it%u2019s hard to get it much accurate. You can%u2019t get accurate enough to use, and so they get it as near as they can and then take the machine like we have here and run it through a machine that makes all four sides slick and the same size. Then they make the walls all line up and all, and it makes it work a lot better.

DG: Is there anything you%u2019d like to tell us that we haven%u2019t asked you?

YE: I was hitting just a little bit ago on that and I got%u2026

DG: %u2026You got sidetracked. That happens to me all the time.

KB: I probably asked another question.

YE: Blank, I drew a blank.

DG: I don%u2019t have any more.

KB: I know. I believe I%u2019ve got everything.

DG: If you%u2019ve finished all of yours, I%u2019ll get this paperwork out.

KB: I believe I have.

DG: Okay. Well, let me turn this off then.

KB: Anything else?

YE: Give me one more minute. [Laughter]

DG: Okay, that%u2019s fine. We%u2019re in no hurry, but we don%u2019t want to keep you because I know you%u2019re anxious to get back to work. [Laughter]

YE: They can take care of me all right.

DG: [Laughter] I%u2019m just teasing.

KB: Let me ask you this, %u2018cause I meant to ask you this when she brought up Home Depot and all. But before then, before the big companies like that, was there a lot of competition for you?

YE: No, no, no. No, I had the field about to myself. I was the only place around here that would dress people%u2019s lumber. They%u2019d bring it in here and word got out; didn%u2019t have to advertise. They%u2019d bring that stuff in here. Yeah, one thing, I never worked on Sunday unless that machine broke down. And I worked all day Saturday. It was Saturday at ten o%u2019clock and we still didn%u2019t have it ready to go, I wouldn%u2019t go to church the next day. I had that thing ready to go Monday morning, %u2018cause I had people waiting on the orders, you know, and I always needed to get more out to keep more income, keep enough money to pay the help. First National Bank was good to me. I%u2019d borrow money from them once in a while and I%u2019d pay it back.

KB: Well, that%u2019s good. That%u2019s good. Church was very important to people at that time, weren%u2019t--?

YE: What?

KB: Church. Was it very important?

YE: Oh, yes ma%u2019am.

KB: Very important.

YE: Oh, yeah. Right. Zoar Church down there. I%u2019m still a member there. I guess I know ( ) down there.

KB: Which one?

YE: Zoar, right here. But it was a wooden building; had a basement, two or three classrooms down there, and a wood heater down there and a wood heater upstairs, a big ol%u2019 round one, almost as big as that one right there. That%u2019s how they heated it. There was a curtain between some of the seats upstairs. Had a curtain for one class, a men%u2019s class here and women%u2019s class here%u2026

DG: %u2026Oh, really?

YE: Yeah.

KB: Very good.

DG: Well, listen, we don%u2019t want to take any more of your time. I do have some paperwork that we need to get you to sign, so I%u2019ll go ahead and turn this off.

END OF INTERVIEW

Mike Hamrick, March 9th, 2010

Born July 30, 1921, about a half mile from the Broad River in Cleveland County, Mr. Ellis explains the course of the river as it flows from Hickory Nut Gorge through the Carolinas and the name changes it undergoes along the way, finally becoming the Cooper River in Charleston.

Mr. Ellis tells how he found a niche in the lumber business, which no one else was filling, that gave him the incentive to start his own business—Ellis Lumber Company. The niche was “dressing” rough lumber to make it ready for constructing houses and other buildings. The company has continued to be very successful over the years, helped by his discovering another niche—that of providing the type of lumber appropriate for building log homes, a very popular type of housing in the mountains of North Carolina.

Mr. Ellis also talks about music. His father, Gordon, played the fiddle and guitar and was part of a three-man band. While he, Yancey, tried to play the guitar, he was not successful and finally gave up on it. He knew of Earl Scruggs’ ability to play the banjo from the time Earl was twelve years old and performing locally. He kept up with him through the years, even visiting him in the hospital after Earl’s bad automobile accident. He recalls the time that Earl visited him in his home, pulling up in a “big ol’ long limousine with ‘Martha White Flour’ all over the side of it.”

Profile

Date of Birth: 07/30/1921

Location: Shelby, NC